A remote island has been chosen by Sri Lanka’s government for the burial of Covid-19 victims from the minority Muslim and Christian communities.

The government previously forced minorities to cremate their dead in line with the practice of the majority Buddhists. It claimed burials would contaminate ground water.

But the government backed down last week in the face of vehement criticism from rights groups.

Islam prohibits cremation.

Iranathivu island in the Gulf of Mannar is the designated site for burials.

It lies some 300km (186 miles) away from the capital, Colombo, and was chosen, the government says, because it is thinly populated.

Human rights groups, including Amnesty International, and the United Nations had also raised objections.

Government spokesman Keheliya Rambukwella said a plot of land had been set aside on the island, according to the Colombo Gazette.

The World Health Organization has provided extensive guidance on how the bodies of those who have died from Covid should be handled safely, but points out there is no scientific evidence to suggest cremation should be used to prevent infection.

“There is a common assumption that people who died of a communicable disease should be cremated to prevent spread of that disease; however, there is a lack of evidence to support this. Cremation is a matter of cultural choice and available resources.”

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has said the policy on cremations failed to respect the religious feelings of the victims and their family members, especially Muslims, Catholics and some Buddhists.

The forcible cremation of a 20-day-old Muslim baby intensified criticism of the policy.

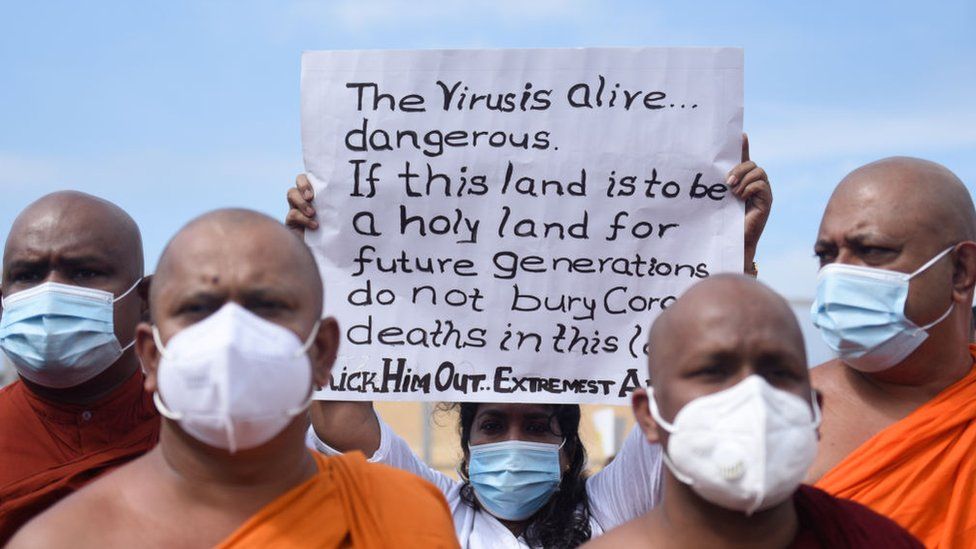

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESBut some Muslim and Christian leaders have reacted negatively to the government’s latest move.

“This is a ridiculous and insensitive decision,” Hilmy Ahamed, vice-president of the Muslim Council of Sri Lanka, told the BBC. “This is an absolute racist agenda. The saddest part is it’s almost pitting Muslims against the Tamils living in those areas.”

Fr Madutheen Pathinather, a priest living on the island, told the BBC the community was “deeply pained” by the decision. “We strongly oppose the move. This will cause harm to the local community.”

He said the island’s population of around 250 Tamils, who were displaced due to the civil war in the early 90s, only returned in 2018.

Adding to insult

By Anbarasan Ethirajan, BBC World Service South Asia regional editor

They say they have to travel far away from their homes to bury their dead and it will be difficult to pay homage to their buried relatives during festivals and anniversaries.

More than 450 people have died with Covid in Sri Lanka so far and around 300 are from the minority communities.

The government’s hurried announcement seems to coincide with the ongoing UN Human Rights Council meeting in Geneva where it has faced strong criticism from the UN human rights chief, Michelle Bachelet, over the issue.

The decision to lift the burial ban followed a visit by Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan.

Sources told the BBC that Sri Lanka sought Pakistan’s support at a United National Human Rights Council session, which is expected to consider a new resolution on mounting rights concerns in Sri Lanka, including over the treatment of Muslims.

Sri Lanka is being called to hold human rights abusers to account and to deliver justice to victims of its 26-year-old civil war.

The 1983-2009 conflict killed at least 100,000 people, mostly civilians from the minority Tamil community.

Sri Lanka has strongly denied the allegations and has asked member countries not to support the resolution.