Image courtesy of LankaSara

Kishaly Pinto-Jayawardene.

Has anyone spotted the very large elephant in the ‘Batalanda’ torture chamber, I wonder?

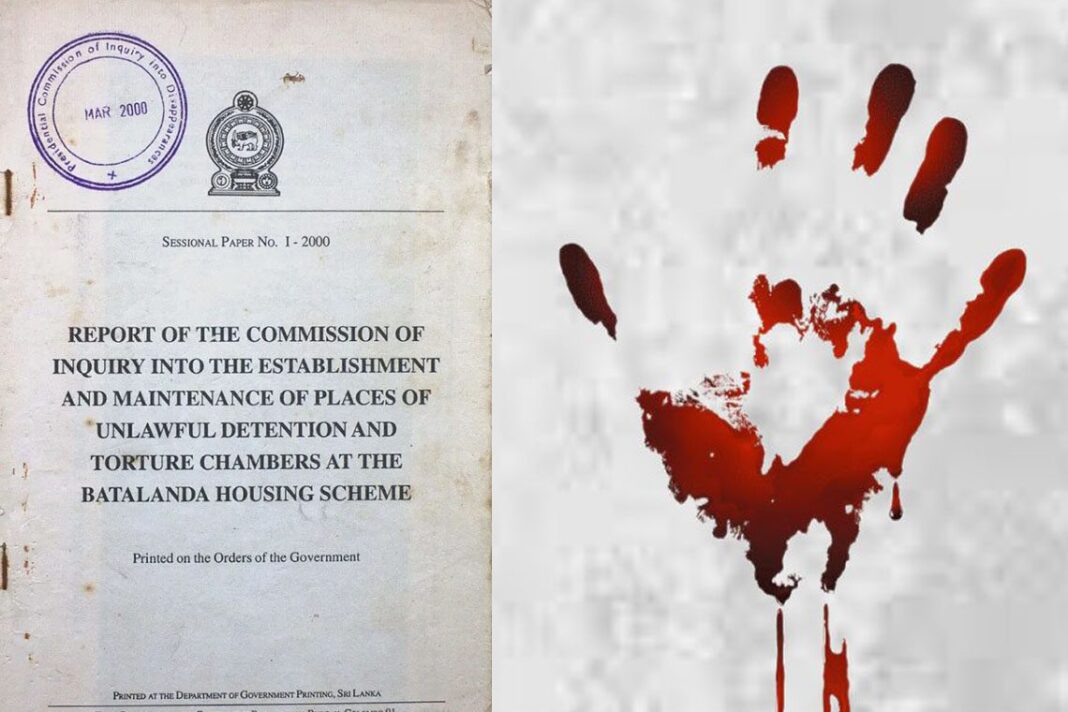

The ruse of ‘tabling’ the Commission Report

To be perfectly clear, this is not simply a word play on the United National Party’s (UNP) party symbol and its ruthless state-terror tactics to quell the South’s second youth uprising (1987-1989). That included employing the Batalanda Housing Scheme to torture suspected ‘Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna’ (JVP) insurrectionists. Rather, the question speaks to systemic impunity that also visits the National Peoples’ Power (NPP) Government led by a now rebranded JVP.

For those yet confounded by the tortuous intricacies of how Sri Lanka persistently evades and politicises accountability, we may pose a further probing question. What is the one factor in common between the shrill cries of the NPP Government which tabled the Batalanda Commission of Inquiry Report in Parliament with a predictably partisan flourish and former President and the UNP’s party leader, Mr Ranil Wickremesinghe?

Mr Wickremesinghe, as Minister of Industries at that time, was found ‘indirectly responsible’ in that Report for the Batalanda abuses. In short, that common factor is the singular insistence of both that the Commission of Inquiry report must be ‘tabled’ for its findings to proceed further. This is an entirely wrong premise. No wonder that the Cabinet spokesman awkwardly stammered when asked to explain this stand by journalists a few days ago.

A welcome distraction for the Government

In fact, the list of Commission of Inquiry reports that have not been put before Parliament but in regard to which, prosecutions have commenced, some successful but others mostly not, are too long to be listed here. I will return to that point later. Of course, the former President’s bizarre claim to a combative Al Jazeera journalist during a recent talk show in London amounted to a wholly new level of idiocy.

Mr Wickremesinghe argued that if the Batalanda Report was not tabled in the House, ‘it does not exist’ or words to that effect. From that came an unedifying hullabaloo which shot straight to the virtual stratosphere, becoming manna from heaven for the NPP Government beset with its own ineptitude if not complicity in perpetuating state impunity, including a startling inability to locate a fugitive Inspector General of Police (IGP).

That IGP has been accused by the Attorney General’s Office of half a dozen sins including running a criminal para-military gang. Confounded and confused, the public is scratching its collective head over the preposterous spectacle of the manhunt for the police head, much like Baroness Orczy’s (infernal) Scarlet Pimpernel, ‘here, there and everywhere.

Why confine the parliamentary debate to Batalanda?

But to return to the all-absorbing topic of the Batalanda Report, an early example of its political usage emerged from a Supreme Court ruling upholding the fundamental rights violations of police officers disciplined on its findings (Jayaratne v. de Silva and others, 1998). Decades later, the Leader of the House trumpeted in tabling the Report, that this had been hidden in the dusty corners of the Presidential Secretariat.

Inferentially the Report is being publicised only now, we are told. That is incorrect. Printed as a Sessional Paper in 2000, the Report was widely accessible. Meanwhile the Government has announced that a two-day debate will be held on its contents and that it will be forwarded to the Attorney General. As to how the prosecutor will open this freshly mined Pandora’s Box of political power-play remains to be seen.

That apart, why does Parliament not discuss other Commissions of Inquiry reports? This includes the Special Presidential Commission Report on the Assassination of Vijaya Kumaratunga (1988). Though the killing occurred at the hands of the militant wing of the JVP, the (political) finding of that Commission was that government politicians were ‘indirectly responsible’ on scant evidence.

A transparent tactic with a dual motive

And then we have the far more credible Commissions inquiring into Enforced Disappearances and Extrajudicial Executions who issued excellent recommendations on addressing state impunity only to be blatantly ignored. But that will not happen. In other words, the tabling of this Report is a transparent tactic with a dual motive by the Government. This is to gather maximum political mileage and potentially eliminate an opponent to the happy cheers of their (now rather discontented) supporters.

Not that one need shed any tears for former President Wickremesinghe whose colossal contempt for the Rule of Law has often been the trenchant subject of criticism in these column spaces. But the continuing parade of Commissions of Inquiry reports as a fascinated audience watches agape, makes one’s blood boil. Long before “Batalanda’ became passing entertainment on a talk show overseas, this atrocity had been a cornerstone of the fight for legal accountability by Sri Lankan activists.

For example, the self-admitted role of politicians and senior police officers implicated in the ‘Batalanda’ operation was in regard to ‘directing counter-subversive operations.’ These cases may have been textbook examples of the legal doctrine of command responsibility if our courts had been a tad bolder in affirming this in ‘situations of war.’ But Sri Lankan jurisprudence is equivocal to that effect.

Increase of prosecutorial powers to no effect

More importantly, there was no political or prosecutorial. One consequence of this advocacy however was an amendment to the Commissions of Inquiry Act in 2008 which permitted the Attorney General, ‘to institute criminal proceedings…based on material collected during the course of an investigation or inquiry…’ (Section 24, Amendment Act, No 16 of 2008).

Neither this Amendment nor the parent Act of 1948 requires the tabling of a Commission of Inquiry Report in Parliament. But to all intents and purposes, that Amendment remained a dead letter and Commission reports continued being politically driven. To reiterate, the Batalanda atrocity was just one of multifarious illegal detention centres, from the Sooriyakande massacre to the Bathegama (temple) torture site.

These included a dark blood spattered room in the Faculty of Law, University of Colombo where UNP Black Cat militaries tortured JVP affiliated students in the night during the nineteen eighties even as we studied the discipline of the law in daytime. To this day, students fear to go near the room from which, they say, ghostly cries emanate. Moreover erstwhile state torture camps are a stone’s throw away from atrocities committed by the JVP and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)

A blood splattered soil pleads for justice

These sites where public intellectuals, buses of civilians and pilgrims, Presidents, public servants and critics were assassinated by supposed ‘freedom fighting’ outfits are infamously edged in blood and stone across the land. Not a single inch of soil has been spared this bloodletting or a single family for that matter. One final thought surfaces albeit with a grim edge of humour.

For more than a decade, the JVP had painstakingly ‘rebranded’ itself as the NPP to escape the extraordinary cruelties of a blood-spattered past as they were rebuffed time and time again by an unforgiving electorate. But if the fracas over the ‘Batalanda atrocity’ had preceded Sri Lanka’s Presidential and Parliamentary elections, that effort would have perchance been unnecessary.

Rather, the JVP could have emerged as pure as the driven snow as it did this week, tabling the Batalanda Report in blinking wide-eyed innocence of multiple brutalities on its part, including killing children of public servants and forbidding funeral rites of victims. In the final reckoning, neither the Sri Lankan State nor the terror groups that it defeated can, like Pontius Pilate, wash their hands of blood.

Partisan parliamentary antics cannot erase that fundamental truth.

(Courtesy of The Sunday Times.16.03.2025)