Anura Kumara Dissanayake of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) has officially been appointed Sri Lanka’s next president. It marks a remarkable turnaround for a party that staged two violent insurrections against the Sri Lankan state. Indeed, it was a result that left many observers around the world somewhat taken aback by the direction Sri Lanka may be heading in. For those on the island, however, this is not a surprise. Discontent had been growing in the Sinhala South over the state of the economy, despite claims from the ruling Wickremesinghe regime that recovery and prosperity were soon to come. With the island’s financial woes continuing, Sinhala voters chose to lurch towards the extremes of the polity. But Dissanayake and the JVP are not all change. Though the party has been steeped in a confused mixture of ideologies, from self-proclaimed Marxism to Sinhala populism, at its core it is deeply racist and firmly chauvinistic. As long as it remains so, Sri Lanka’s instability will continue.

Driven by concerns over the ailing economy and cost of living crisis, the National People’s Power (NPP) alliance that Dissanayake heads made a host of promises coming into the polls. Chief amongst them was the “renegotiation” of the desperately needed US $3 billion bailout loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The terms of any IMF restructuring program were always going to be painful and the prospect of any sort of modification is slim. Any tampering may lead Sri Lanka’s already fragile economy to collapse once more, with both the IMF and the previous regime sounding repeated warnings. It remains to be seen how stern Dissanayake’s approach to the global body will be, but creditors around the world will be watching closely. With dollar bonds and stocks sharply declining in the immediate reaction to Dissanayake’s victory, the initial signs do not seem promising.

For Eelam Tamils, the entire election was yet another demonstration of the futility of engaging with Sri Lanka’s flawed electoral system. The turnout in the North-East, the lowest amongst the island, reflects how jaded many feel and the distrust they still hold in Sri Lanka’s institutions. Though Tamil participation in presidential elections has traditionally been low for decades, the months of infighting within the Tamil political establishment disillusioned many even further, who for 15 years since the Mullivaikkal genocide have been looking for fresh and principled leadership.

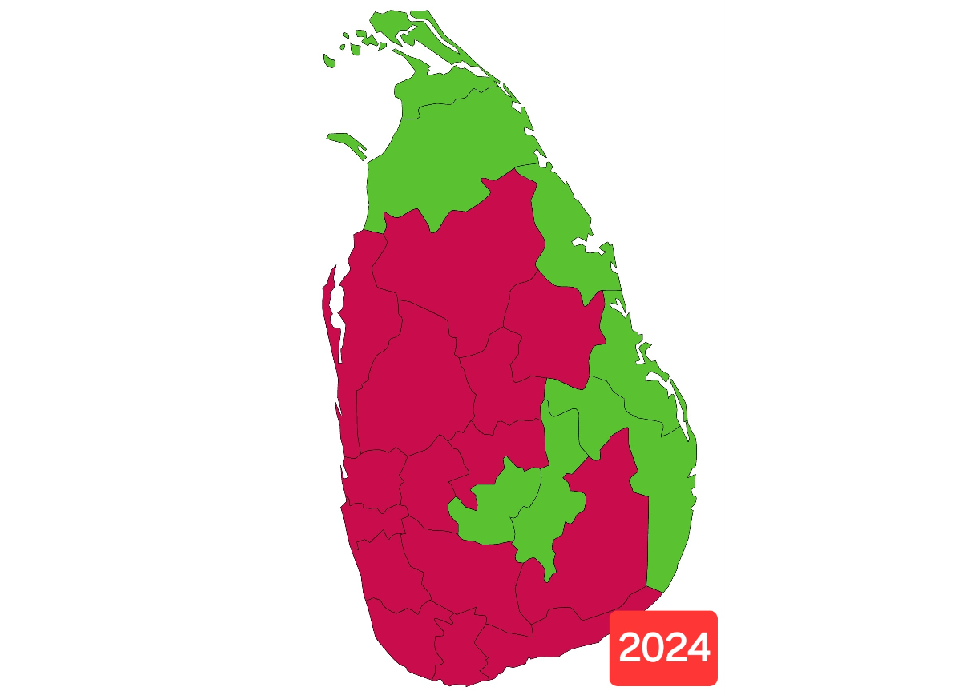

In light of this, some Tamils chose to boycott the election, whilst others chose to back a hastily declared ‘common candidate’, despite calls from some parliamentarians not to do so. Given that his candidacy was only declared weeks before the polls, the over 200,000 votes he received are not insignificant and offer a glimpse of what a more prepared campaign could have offered. Others decided to vote for Sajith Premadasa, seeing him as the lesser of all the evils on offer. Premadasa is not unfamiliar to Eelam Tamils, who voted overwhelmingly for him in 2019 in a bid to keep Gotabaya Rajapaksa out of office. And though he is a staunch Sinhala nationalist who continues to surround himself with war criminals and deny justice for the Tamil genocide, he was the only Sinhala candidate to state he would fully implement the 13th Amendment – a flawed provision but one that nonetheless devolves limited powers. Tamil parliamentarian M A Sumanthiran who openly and controversially backed Premadasa, even told voters that he was in favour of the devolution of powers based on a unified North-East and hoped the Opposition Leader would deliver. Yet despite Tamil support across the North-East, the very structure of the Sri Lankan state and its electoral system means that their efforts, much like in 2019, were futile.

Dissanayake, on the other hand, made it resoundingly clear during his presidential campaign that he would oppose such devolution. In recent weeks alone senior figures within the JVP repeatedly burnished the party’s Sinhala nationalist credentials to the southern masses, speaking on how they stood opposed to Tamil autonomy and vehemently backed a military offensive that would culminate in the Mullivaikkal genocide. Dissanayake himself vowed to protect Sri Lankan war criminals and dismissed calls for accountability. Tamils are well aware of the long racist history of the JVP whose bloody 1987 rebellion was driven by concerns that the Tamil liberation struggle would sweep across the North-East. The newly elected Sri Lankan president has himself protested peace talks with the LTTE, rejected joint post-tsunami aid distribution with Tamils, endorsed Mahinda Rajapaksa on a platform specifically opposed to a cease-fire, backed the tearing of a united North-East, repeatedly praised the Sri Lankan military’s offensive and pledged to ensure Buddhism remains occupying the “first and foremost” place on the island. Whilst his politics and that of the JVP may have evolved in some aspects, unless those positions are firmly rebuked, there seems little prospect of change.

With Sri Lanka still on a “knife edge”, as per the words of the IMF, and a parliamentary election now on the horizon, there will be more turmoil ahead. Tamils will be hoping amidst this, more principled leaders will emerge from the North-East and that Dissanayake will start putting his promises of ‘system change’ into action. His pledge to stamp out corruption, for example, is undoubtedly welcome. But it cannot be seen in isolation. As the UN Human Rights chief highlighted this month, the entrenched impunity for human rights violations “has manifested itself in the corruption, abuse of power and governance failures that were among the root causes of the country’s recent economic crisis”. There is an opportunity for Dissanayake to put an end to all of that and bring about a radical transformation of the state. His initial actions, however, including his promotion of an accused war criminal, are not encouraging.