Cartoon: Courtesy of The Morning.

President Maithripala Sirisena’s implied criticism of the Sri Lankan judiciary when speaking at the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) convention this Tuesday, referencing himself as the Mahanayake (seniormost prelate) of a Nikaya (chapter) being educated by the head monk of a village temple invokes strong and unequivocal condemnation in no uncertain terms.

What is in issue here however is at its very core, the constitutional separation of powers involving checks and balances between the executive, the legislature and the judiciary and must be understood as such. Assuredly this is not a dispute between monks of whatever rank or seniority as the case may. Illustrations of this nature cannot be justified as being addressed to a political audience as the President may strive to explain.

Recognising ominous undertones

On the contrary, there are familiarly ominous undertones that reflect executive coercion which all Presidents have trifled with in the past. From JR Jayawardene to Chandrika Kumaratunga and Mahinda Rajapaksa, this was the one besetting and common sin that all political executives have been guilty of, without exception.Threats and intimidation of the judiciary ranged from the houses of judges being stoned, to Parliament being used as a forum to cast aspersions on individual judges and worthy judicial officers being disregarded for promotions because they happened to give decisions that angered politicians. It is hoped that Maithripala Sirisena will not add his name to this less than illustrious list.

Not so long ago, the President of the International Commission of Jurists and formerly Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations for Human Rights in Cambodia and Justice of the High Court of Australia, Michael Kirby described a judge without independence as‘a charade wrapped in a farce inside an oppression.’ Sri Lankans had reason enough to recall this crackling description during the past decade and a half when the integrity of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka was politically eroded from within the most fiendish manner possible by individuals sitting in the Office of Chief Justice.

Nevertheless, one significant achievement of the coalition Sirisena-Wickremesinghe administration from 2015 to its unhappy ending earlier this year was to allow the judicial institution to draw a breath and slowly set about redeeming itself from the tormented ghosts of the past. This, the judges on the whole are doing with distinction. A few days ago, it was reported that the Kurunegala Chief Magistrate had ordered the police to remove political posters in support of various politicians and political parties in Kurunegala. These assertions of judicial strength are to be applauded in a background where judicial timidity is more often the norm. Today, we see a welcome resurgence of a public preoccupation with issues of constitutional justice and effectively working the Constitution in this regard.

Undermining the judiciary must be resisted

In the nineties, rights focused interventions into governance became a matter of course though the assumption of judicial authority in Sri Lanka.However, as authoritative pronouncements reining in the executive were delivered by the Court, tensions exacerbated between the executive and the judiciary. The list of infamies committed by enraged politicians was long, including installing favourites as Chief Justices, And the consequences to Sri Lanka’s judicial systems were incalculable. While across the Palk Straits, Indian judges and lawyers worked the transformation of formal legal systems to living law, this country faltered. The movement of a dedicated constituency believing in the law through socially conscious lawyers and public interest groups together with an investigative press and an interested public stopped in its tracks.What the country suffered thereafter was irreparable. We do not want to return to that tortured past ever again.

Therefore thinly disguised Presidential statements that seek to undermine that process must be met with determined civil resistance, learning from the past when the silence of good men and women resulted in the subversion of the Court and the citizens being left with no recourse when their rights were violated.

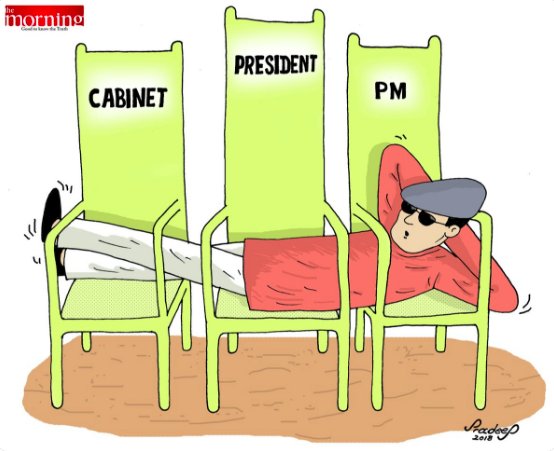

This constitutional doctrine of separation of powers stands threatened in other fundamental ways as well. When the President says that, even if all two hundred and twenty five members of parliament ask him to appoint RanilWickremesinghe as the Prime Minister, he will not do so, that is a direct clash between the executive and the legislature, no more and no less. Needless to say, this goes beyond the political agendas and personal animosities of the three men at the vortex of Sri Lanka’s constitutional crisis, President Sirisena, Prime Minister RanilWickremesinghe and former President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

A tragedy of no small proportions

As history may perhaps record with some compassion, it is a tragedy of no small proportions that presidential candidate MaithripalaSirisena who came into national political prominence in the election campaign four years ago showcasing an entirely different persona to the arrogance and macho images of his predecessors could have unpleasantly metamorphosized in such a short period of time to what the country sees now on the political stage.

There is also a thinly disguised class bias in the political chaos that has unfolded before us. On the one hand, the President labels Ranil Wickremesinghe as a non-respecter of ‘our culture and traditional values’ as he did again this week at the Sugathadasa Stadium. His or rather, the former President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s supporters giggle on the steps of the Supreme Court saying that Wickremesinghe and his lawyers are only adept at reading the English texts of the Constitution. On the other hand, Wickremesinghe’s frenzied and outraged supporters lash out at the President with impunity, resorting to rude name-calling that is traceable to the President’s rural roots. Both these characterizations are equally unfortunate.

Long decades after colonial rule, it is a pathetic indictment on this country and the people that divisions and divides based on ‘traditional values’ or cultural norms (often more Victorian in origin rather than indigenous) and insults based on familiarity or not as the case may be, with a colonial and alien language should form the basis of national political debate. There is something far more wrong in Sri Lanka, the political culture and indeed, society itself than the text of a Constitution over which lawyers are quarreling.

That much is certain.

-Sunday Times