By Mithun Jayawardhana/Ceylon Today.

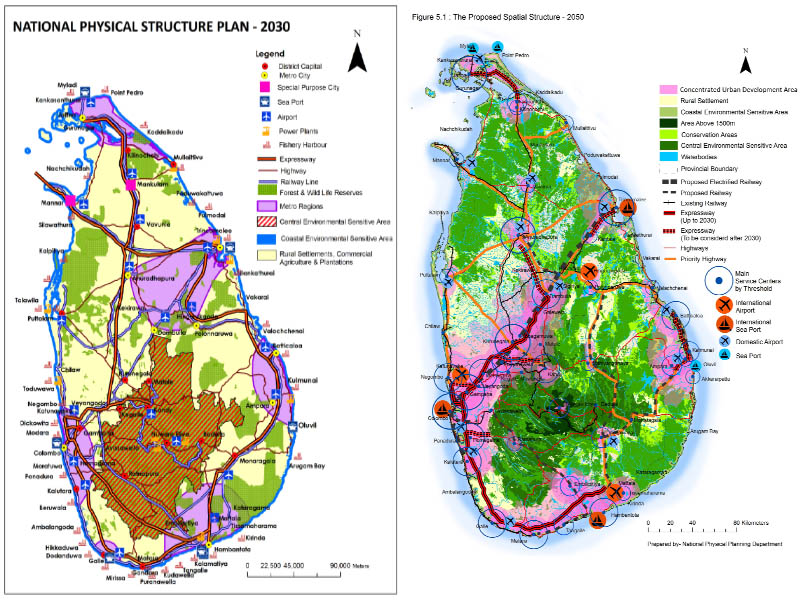

Sri Lanka’s National Physical Plan (NPP) was conceived as the country’s highest-level spatial blueprint—a long-term, technocratic roadmap intended to guide land use, infrastructure, environmental conservation, and regional development across a 30-year horizon. Instead of responding to political winds, it was designed to be the compass that directs governments, ensuring that the country’s physical growth remains coherent, sustainable, and nationally beneficial.

Yet, two decades since its inception, multiple revisions later, and in the aftermath of one of the most destructive natural disasters in recent memory—Cyclone Ditwah—the question looms larger than ever:

Has the National Physical Plan simply become another political document?

Interviews with senior officials, historical analysis, expert assessments, political criticism, and the current government’s own planning rhetoric all point to a troubling conclusion: while the National Physical Planning Department (NPPD) continues to produce technically sound spatial plans, these documents have increasingly been overridden, reshaped, or shelved altogether to suit fluctuating political agendas.

The NPP’s sudden return: Why 2025 matters

Two major developments have propelled the National Physical Plan back into the spotlight in late 2025.

Cyclone Ditwah—December 2025—left sweeping destruction across the island. More than 5,000 homes were damaged, dozens of roads and bridges collapsed, and rail lines were washed away. In the wake of that devastation, the government faced a stark reality: the unplanned reconstruction approaches used for decades were no longer viable.

For the first time in many years, planners are turning back to the NPP’s ‘Environmentally Sensitive Areas’ maps to determine where reconstruction must not take place. Entire settlements—historically built in floodplains, wetlands, and landslide-prone zones—are now under review.

A senior National Physical Planning Dept (NPPD) officer put it bluntly: “The National Physical Plan was originally designed as the technical operating system for the country. But for years, it became a political manifesto. Now—after Ditwah—it has resurfaced not as a development document, but as a blueprint for survival.”

Climate finance strategy

Sri Lanka’s new climate finance strategy, launched in October 2025, is aimed at securing green investment and climate-adaptation funding. But global financiers require one guarantee above all: a stable long-term physical plan that cannot be rewritten at every Election.

Yet the NPP’s historical instability makes investors nervous. Each revision, each political rebranding, and each deviation from the plan erodes credibility.

A document in flux: The 15-year pattern of political alteration

A review of the last decade and a half shows a clear pattern: the National Physical Plan shifts not with demographic trends or environmental realities but with political slogans.

The shift from 2030 to 2050, and then abruptly to 2048, reveals not planning logic but political messaging. The 2048 horizon was chosen largely because it marks the centenary of independence—forcing planners to retrofit projections around a symbolic year.

One senior officer summed it up: “When politics decides the timeline, the plan stops being a plan.”

Inside the politicisation: How technical planning gets distorted

For years, NPPD planners identified the Colombo–Trincomalee Economic Corridor as the most logical axis of development—a zone where 35–40% of the population resides and where east–west connectivity would stimulate balanced growth. But politicians have repeatedly deprioritised it.

Some administrations preferred Southern-centric development, reshaping the plan around Hambantota and Matara, where they enjoyed electoral strength. Others emphasised Western Province-led growth to please urban business constituencies. The result: spatial logic replaced by political convenience.

In any functional planning system, the physical plan should determine where highways go. In Sri Lanka, highways often determine how the NPP is rewritten.

Planners and Engineers—such as Transport Expert Prof. Amal Kumarage—have long criticised the politically motivated deviations in the Central Expressway routing. These reroutings–

-

-

- avoided certain electorates

- skirted around influential landowners

- added unnecessary distance

- tripled land acquisition costs

-

What should have been an economically transformative corridor has instead become a politically shaped debt burden.

The Urban Development Authority, driven by commercial incentives and political direction, frequently overrides the NPPD. Instead of national spatial logic, ‘spot planning’ dominates: selling prime lands, launching ad-hoc projects, and modifying zoning for investors.

This dual-planning system produces fragmentation, conflict, and in many cases direct contradictions between agencies.

Why the NPP fails: Structural and legal weaknesses

A senior NPPD officer summed up the central flaw: “The Plan is law, but the President is above the law.”

Three weaknesses are repeatedly cited: The National Physical Planning Council (NPPC)—the approving authority for the NPP—is chaired by the President. If the President disagrees with a recommendation (such as restricting development in a politically strategic district), that recommendation does not survive the final draft. The NPP is not tied to the national budget.

This means the Treasury can fund projects completely outside the plan—undermining it from within.

Even when officially gazetted, the plan has no punitive provisions. Local authorities can approve construction in protected zones without consequence. Thus, the NPP is legally present—but politically irrelevant.

Expert insight: Planning without integration leads to instability

Engineer M.G. Hemachandra emphasised the critical need to integrate the National Plan (economic strategy) with the National Physical Plan (spatial strategy).

He warned:

“Building roads without aligning them to national economic priorities only increases imports—cars, luxury goods—and drains foreign reserves. Roads are important, but spatial planning must match economic planning.”

Hemachandra argues that Sri Lanka’s national priorities must be clear, consistent, and synchronised. Without this, the nation faces–

-

-

- arbitrary borrowing

- inefficient infrastructure

- vulnerability to bankruptcy

- planning structures that break down in crises

-

Political reaction: Opposition accuses government of operating without a plan

Both the SJB and the SLPP accuse the current government of lacking a coherent national physical planning strategy.

Ranjith Madduma Bandara, SJB General Secretary, said: “This government has no plan — just no national physical plan. They have only ‘talk’: ‘no action’. Their failure to follow a consistent plan is dragging the country into crisis.”

SLPP General Secretary Sagara Kariyawasam argued: “The government has been in power for over a year and still has no national physical plan. They continue Mahinda Rajapaksa’s and Ranil Wickremesinghe’s projects because they have none of their own. With disasters like this, the absence of a plan is disastrous for the economy.”

This bipartisan criticism signals a growing consensus: the NPP is not functioning as a stable framework.

The President’s vision

In March 2025, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake declared that Sri Lanka could become an attractive global tourist destination through modern urban planning that moves beyond ‘traditional construction methods’.

He advised officials to –

-

-

- embed Sri Lankan identity into city planning

- protect rural livelihoods

- link rural and urban economies

- avoid development that erases cultural character

-

These priorities are significant, especially in a political context where urban megaprojects have historically overshadowed rural concerns.

But the key question emerges:

Is this a long-term national direction—or merely another government’s interpretation layered onto an already politicised document?

Without legislative insulation or institutional reform, even well-intended planning philosophies risk becoming transient political branding.

Attempts were made to contact W.T.H. Ruchira Withana, Director General of the NPPD, and Bimal Rathnayake, Minister of Transport, Highways and Urban Development, but they were unreachable at the time.

Historical roots of the institution

The NPPD evolved from the Town and Country Planning Department, established under the Town and Country Planning Ordinance No. 13 of 1946. The amendment via Act No. 49 of 2000 expanded the mandate to produce a National Physical Planning Policy and Plan—an attempt to centralise and stabilise physical planning.

Yet, the institution’s historical evolution cannot shield it from political interference.

The real costs of politicising the NPP

Unplanned development in wetlands and floodplains increases the severity of disasters like Cyclone Ditwah. Ignoring ecological zoning destroys natural defences. Each government’s new projects leave behind a patchwork of incomplete, contradictory plans. Foreign investors will not commit to long-term projects without confidence that the physical plan will remain unchanged through the elections. Cancelled or rebranded projects cost billions in sunk costs. Rural communities suffer most when political geography replaces spatial logic.

Can the NPP be saved? Pathways to depoliticisation

Experts propose three urgent reforms: The NPP should be ratified by Parliament—not merely approved by Cabinet. Any change should require a two-thirds majority. Similar to the Election Commission, staffed by fixed-term technocrats rather than political appointees. Treasury funds must not be released for any mega-project not listed in the NPP. If implemented, these reforms could restore the NPP’s authority.

A blueprint at a crossroads

So, has the National Physical Plan become another political document?

Yes—so far.

Its revisions have mirrored electoral agendas, its implementation has been inconsistent, and its authority has been repeatedly undermined by short-term politics.

But, the post-2025 landscape—shaped by debt restructuring, climate vulnerability, and Cyclone Ditwah’s devastation—demands a change. Sri Lanka can no longer afford a politicised physical plan.

President Dissanayake’s call for culturally grounded, balanced development offers a potential turning point. Yet without structural reform, the NPP risks becoming merely the latest political vision in a long line of forgotten visions.

The National Physical Plan must become what it was always meant to be: A stable, non-political, technocratic foundation for Sri Lanka’s future—not a document rewritten with every government.

Only then can Sri Lanka protect its environment, attract investment, build climate resilience, and ensure that development serves the nation rather than political cycles.