Excavated Truths: The graves came to light when the main accused declared in court, “I can show you hundreds of bodies buried in Chemmani”. Image courtesy – Sakuna M. Gamage

Kamanthi Wickramasinghe Daily Mirror.

- The main convict in the Krishanthi Kumaraswamy case revealed the Chemmani mass grave in 1998, upon being sentenced to death in 1998

- Krishanthi Kumaraswamy, the 18 year old, who was raped under the hands of several military personel, was a bright student who had received seven distinctions for her O/Ls

- Because the military personnel were interviewed by fellow military police who believed they were “their people”, it was easier to obtain confessions from them

Ongoing excavations at the Chemmani mass grave reveal harrowing atrocities committed during the war. But this mass grave site would have been a secret buried under Lankan soil if not for a statement made by a death row convict. The convict, who is the main accused in the Krishanthi Kumaraswamy case, revealed the Chemmani mass grave in 1998 upon being sentenced to death. Recently, the Supreme Court rejected a petition filed by this convict and others who sought relief on the grounds that they have been on death row for several years. They argued that they should be considered for a Presidential Pardon if they are not being executed or have their death sentences commuted to life imprisonment.

|

| Prashanthi Mahindaratne |

|

| Krishanthi Kumaraswamy |

In this backdrop, the Daily Mirror sat down for an exclusive interview with Prashanthi Mahindaratne, state counsel in the landmark Krishanthi Kumaraswamy case prosecuted during the ongoing civil war. She reflected upon the brutality of the crime and how the investigators cracked the case to convict the perpetrators of rape and murder. The prosecutors were determined to advance the charge of rape on perpetrators as it was one of the first instances of using rape as a weapon of war.

Initial reports

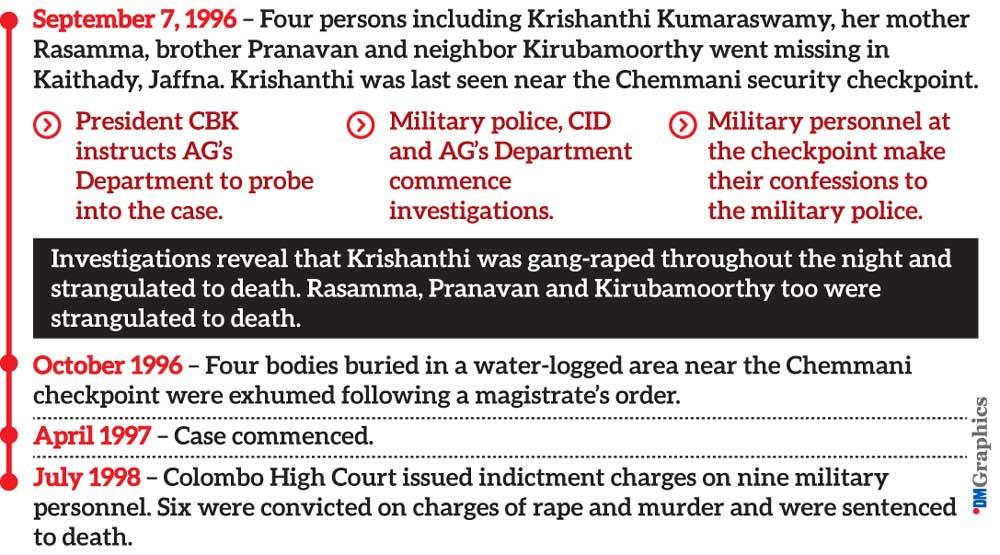

On September 7, 1996, four people went missing in Kaithady, Jaffna. One of them was a girl by the name Krishanthi Kumaraswamy (18), a student of Chundikuli Girls’ School who had just sat for her A/L chemistry paper. She was a bright student who had received seven distinctions for her O/Ls. Krishanthi had lost her father, and she had lived with her mother, Rasamma (59) and brother, Pranavan (16), a student of St. John’s College, Jaffna. She also had a sister, Prashanthi, who was in Colombo pursuing higher studies. Both Krishanthi and Pranavan were bright students. Their mother was a former principal of Kaithady Muthukamaraswamy Maha Vidyalaya and was teaching at the Kaithady Maha Vidyalayam at the time of her death. Even though her mother was eagerly awaiting her return from school, she felt uneasy when Krishanthi didn’t return home by afternoon. Subsequently, Rasamma, Pranavan and Siddambaram Kirubamoorthy, a neighbour and friend of the Kumaraswamy family, went missing on the same day.

The incident happened two years after Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga assumed power. Perhaps there may have been thousands more Krishanthis who were raped, killed and/or went missing during the conflict, but couldn’t get the word out due to the lack of nexus with someone who could bring the story to Colombo. It was a lawyer who had initially raised the matter with CBK. Once she heard about the incident, the then Attorney General Justice Sarath Silva was immediately instructed to investigate the case. “She wanted to ensure accountability for whoever was involved because they disappeared in an area where the military was in control,” said Mahindaratne in an interview with the Daily Mirror.

At the time, she was a young prosecutor who had joined the AG’s department in 1991. “This incident happened in 1996. I was called and asked whether I would like to go to Jaffna. Since I was young, I jumped at the chance. There were no commercial flights at the time, and I was accompanied by officials from the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). He also appointed the late Solicitor General D.P. Kumarasinghe to give me guidance,” she recalled.

When Mahindaratne arrived in Jaffna, she had visited the Chemmani magistrate court and was involved with talking to the military police. “This was how it all started. When we started, we didn’t have any evidence at all. We only knew that the area was under military control and that the four missing individuals lived in Kaithady and that there was some talk that they had disappeared at the Chemmani checkpoint,” she added.

Along the trail of evidence

Subsequent investigations revealed that after sitting for her A/L paper, Krishanthi had gone to pay last respects to a deceased colleague with another friend, Sundaram Gauthami. “They were both on bicycles, and they had departed at one point, and she was last seen driving towards Kaithady. From her school, when she comes to Kaithady, she has to pass the Chemmani security checkpoint. This was a route she had taken for many years, and obviously, those who are at the checkpoint would have been familiar with her. Our investigations revealed that she was stopped there and taken into the bunker on the pretext of questioning and was detained forcibly. Somebody probably would have spotted her being questioned there. At this point, her mother was very upset because she didn’t return home and had been asking people about her whereabouts. So their neighbour, Kirubamoorthy, had come and said that he heard she was being questioned at the Chemmani checkpoint. We didn’t know how he got to know it because he was killed in the process,” she said.

Almost immediately, Rasamma, Pranavan and Kirubamoorthy got onto two bicycles; Rasamma got on Pranavan’s bicycle, and Kirubamoorthy, on his bicycle, went to the checkpoint and questioned one Lance Corporal Somaratne Rajapaksha (who is the first accused in this case) about Krishanthi’s whereabouts. “They had told him that Krishanthi hadn’t come home and that she was last seen here, and that they wanted to find out what happened. Somaratne had repeatedly said that they didn’t know anything about it, but these people had persisted because they were more concerned about the girl. The military people had obviously panicked, and subsequently these three were also taken in and were forcibly detained,” Mahindaratne recalled.

But little did they know that they were spending the last few hours of their lives. “That night, the military not only strangulated Rasamma, Pranavan and Kirubamoorthy to death, but they also gang-raped Krishanthi continuously throughout the night. They subsequently strangulated her, and all four bodies were buried in a waterlogged area in Chemmani. When we exhumed the bodies, they were in an advanced state of putrefaction. They were strangulated from ropes and were pulled from both sides,” she explained further.

Support from state machinery

Mahindaratne, to date, gives absolute credit to the military police, without whom this incident would have been buried without any leads whatsoever. Had the military or the military police refused to cooperate with the investigation, the prosecutors wouldn’t have found any substantial evidence to convict the perpetrators. “There was a political will and a will on the part of the military to advance accountability. Our military works on a centralised command, and everything is documented. When suspicions arose about these people disappearing at the Chemmani checkpoint, they knew exactly who was on duty at the checkpoint. At the time, the military police unit was elsewhere. So they called the Lance Corporal and everybody who was on duty at the checkpoint and started questioning them. Of course, the perpetrators felt at ease because they were being questioned by the military police, and they were their own people. So they confessed, and those confessions were recorded by the military police. They told what happened, including the rape and everything that transpired which were important. In most cases, we have circumstantial evidence, and nobody knows what happened other than the accused and the victim. But here, the accused decided to speak to the military police. They showed the military police where the bodies were buried, and the bodies were subsequently exhumed,” Mahindaratne further said.

As the prosecutor of the case, Mahindaratne was determined to get a conviction, and they were very careful in the way they handled the investigation. “The military at the time carried out a campaign called ‘Hearts and Minds’ to win civilian trust because there was no trust between the military and the public. I remember having a conversation with the Commander of the military police in Jaffna, Col. Kalinga Gunaratne, about accountability and the fact that there needs to be investigations on cases of disappearances. So everything worked well, and the CID was interested in cracking the case, the AG’s department was in full gear, and I was transported to Jaffna by the Air Force. This goes on to prove that what you really need is the political will, and that’s where you need that change,” she added.

Cracking the case, one lead at a time

Forty-five days after the disappearance, the bodies were exhumed, somewhere towards the end of October 1996. When the bodies were exhumed, they were in an advanced state of putrefaction. The investigators hadn’t wanted to traumatise the only living member of the family who was living in Colombo, in getting her to identify skeletal remains. “We didn’t even call her to testify. Generally, we call family members to testify, but in that context, we didn’t want to spare her any additional grief. We came out with a very primitive way to identify the bodies under the circumstances. In 1996, we didn’t have DNA testing, and it was long afterwards that Sri Lanka started carrying out DNA tests. However, we still don’t have the full resources to carry out DNA tests on every case. When the bodies were exhumed, their clothes, especially Krishanthi’s clothes, were thrown into the same pit. We saw that every item of cloth had a distinctive dhobhi mark. This mark was how dhobis (laundrymen and women) identified which clothes belonged to which household. It was a very primitive approach, but we had to confirm that these were the four people who went missing in Krishanthi’s case,” she said.

In turn, Mahindaratne and her team had called on the dhobi working in the Kaithady area to testify. He had identified Rasamma’s, Pranavan’s and Krishanthi’s clothes as the clothes he returned to the Kumaraswamy household. Kirubamoorthy’s clothes were identified separately. This was the initial identification of the bodies based on the clothes. Krishanthi’s clothes were distinct – white uniform, red tie, socks and shoes. Mahindaratne was particularly triggered when she saw the uniform as it was similar to her school uniform, except for the colour of the tie. “The courts took that identification as adequate. In addition, Rasamma had had a hernia operation. Regrettably, there were no dental records because it was the height of the war, and they didn’t have proper dental services. There was a surgical record on a hernia which we managed to match, and with that, we managed to identify the bodies,” she continued.

The tragic part of the story was that Krishanthi had resisted when she was initially being gang-raped. According to testimonies, she had given up at some point. When the fourth or the fifth man went to rape her she had asked them to give her some time and she had asked for water. They had brought water in a bucket, and she had just lied down, knowing that it wasn’t a winning battle. Rasamma knew that she had no way out, and she had taken off her Thali and had given it to the first accused and had told him to give it to her family. But he had given it to his sister, which was subsequently recovered during investigations. All three of them had also given their ID cards to the checkpoint. However it was important for the prosecutors to advance the charge of rape because it was the first time the state was investigating a case of rape in the course of war. It was also the first instance of using rape as a weapon of war.

Thinking outside the box

Since Krishanthi’s body was in an advanced stage of putrefaction there was no forensic evidence of rape. “So we had to think outside the box.

We thought we would use the confessions made by the military to the military police. But under the Evidence Ordinance, any confession made by a suspect to the police is inadmissible against the suspect in a subsequent trial against him. So we used Indian jurisprudence and argued that when a civilian confesses to a civilian police there is that tension. But here they are in the same club where a soldier confesses to the military police. We said that this tension wasn’t there, and based on Indian jurisprudence, we argued that prohibition in the Evidence Ordinance does not apply to a confession made by a soldier to the military police. However, even though the Trial-at-Bar upheld it, the Supreme Court rejected it. But we had other evidence. We didn’t want to simply rely on this evidence as we were worried that it might be an appeal issue,” she continued.

The investigators found out that apart from nine soldiers at the checkpoint, there had been two other Police constables. During the discussions with the military police, the investigators observed hierarchical tensions between the police and the military police. It was found that the military used the policemen to bury the bodies, but wouldn’t get them involved in such brutal crimes. “The confessions revealed that the two policemen were not involved in raping the girl but they were involved in disposing the bodies. So we gave them what is called a ‘conditional pardon’. The Attorney General under the Code of Criminal Procedure has the capacity to give a suspect a conditional pardon; the condition being to disclose all and testify against the prosecution of other accused. Since we wanted to advance the charge of rape, the only way we could do it was either to take a gamble with the confessions. But we didn’t have any independent evidence, and these were eyewitnesses. The Supreme Court while rejecting confessions upheld the conviction for rape because the prosecution has still advanced enough and produced enough evidence to prove rape,” she explained.

Another piece of evidence was Pranavan’s bicycle chain cover. It had a badge with the name Honda, and everybody in the area knew it was his bicycle. The badge was recovered from a nearby bicycle garage, and the man at the garage, in his testimony, had confirmed that he found it near the Chemmani checkpoint.

The conviction and another startling revelation

Subsequently, the suspects were arrested, and the bodies were brought to Colombo for examinations by Judicial Medical Officers (JMOs). Even though the bodies were in an advanced state of putrefaction, the JMOs could determine the cause of death, which was strangulation. The prosecutors recovered Rasamma’s thali from the first accused’s sister. With all circumstantial evidence, two independent witnesses who testified about what happened, the Courts found that the prosecution has led to proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Then the accused were convicted of murder and sentenced to death. The Supreme Court affirmed this conviction. “This is why they made an application to the Supreme Court after 27 years, saying that they have been on death row for a long time, demanding their release,” Mahindaratne added.

It was at this point that the main accused made another startling revelation. “There is a tradition in our courts where the judges ask the accused whether they have anything to say before the death sentence is passed on to them. At that point, Somaratne Rajapaksa, the first accused, said, “We are being sent to the gallows for killing four people, but I can show you hundreds of bodies that have been killed and buried in Chemmani.” This is how details about the Chemmani mass grave came about. Once the accused were sentenced, I finished my case, and they started a new investigation into the Chemmani mass grave. At the time they exhumed around 15 odd skeletons,” she recalled further.

Escapes and acquittals

Mahindaratne further recalled several incidents that happened during the trial. The accused, being trained military personnel, had escaped from prison at one point. “They were out at large for a couple of days. All individuals were found except one, and that person, D.V. Indrajith Kumara, is still at large. Whether he is dead or alive, we don’t know, so we proceeded against him in absentia. So he’s a fugitive from justice. Together with him, we indicted nine military personnel. One died while in custody (V.S.V. Alwis) while the case was ongoing. Of the remaining eight, two were acquitted: D.G. Muthubanda and A.P. Nishantha. Muthubanda was acquitted at the end of the prosecution’s case because the court held that the evidence against him was not substantial. Nishantha was acquitted at the end of the trial. Thereafter, six of them were convicted, including the one who is still at large,” she added.

Political will as a catalyst for accountability and closure

The discourse on transitional justice and related mechanisms began during the Yahapalanaya regime back in 2015. The Office on Missing Persons (OMP), Office for Reparations and the Truth Commission were established post the UNHRC Resolution 30/1 co-sponsored by the Yahapalanaya government. But subsequent regimes withdrew from co-sponsoring this resolution and were in denial mode about war crimes and atrocities committed during the war.

Mahindaratne spoke about universal jurisdiction, which is being practised in certain countries. By definition, it is a legal principle that allows states or international organisations to prosecute individuals for serious crimes, such as genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, regardless of where the crime was committed and irrespective of the accused’s nationality or residence. “For instance, Germany prosecuted a former LTTE member for executing policemen who had surrendered during the civil war. This was a case where Germany prosecuted a Sri Lankan who committed crimes against Sri Lankans in Sri Lanka on the basis of universal jurisdiction. Hence, it has been established, and we need to have genuine and credible domestic processes. After all, these are crimes against Sri Lankan citizens by Sri Lankan citizens,” she explained further.

She underscored the fact that it is essential to have a political will to bring about closure for victims of war and that the laws and mechanisms are very much in place. Referring to her contribution in co-drafting the OMP law, she said that it gives extensive powers to commissioners. “If there were a proper system in place, they would have been able to give some answers to the aggrieved families. I have seen how the military maintains all documents, so it’s not a difficult process in my view,” she added.

Mahindaratne further said that the OMP can certainly find out what happened to disappeared persons. It’s not only about a matter of North and East, but what about the South? What about the people who went missing during the JVP insurrections? Hence, there are so many families without closure,” she said.

In her own words, “Acknowledgement is definitely the first step towards bringing about the reconciliation process”. “I was involved in co-drafting the proposed Truth Commission law in 2018. The AG’s department started working on it during President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s tenure. There was an intent to set up a truth commission. In this case, we have made provision for acknowledgement even in Parliament, but we do not know whether these provisions would pass. But there has to be a start. As long as you deny and say that these crimes didn’t happen, how can you reconcile?” she questioned further while adding that it is a shame to know that there are mass graves under our feet.

However, Mahindaratne is hopeful about advancing accountability for some of these cases, given that there’s a political will. She said that it cannot be done without the support of the state machinery. “I could successfully prosecute the case of Krishanthi Kumaraswamy because every institution supported me. The media also assisted us at the time. People in Kaithady were very hurt when this incident occurred. There was mistrust in the government, and they thought it was going to be another farcical process. All lay witnesses were in Kaithady, and they refused to come. The Tamil papers interviewed us, and we told them that the lay witnesses were reluctant to come to Colombo. The articles read as follows; the court is ready in Colombo, the judges are Sinhala, the prosecutors are Sinhala, the CID and everybody else is Sinhala and they are ready to proceed with the case but the Tamil civilians are not cooperating.” Immediately afterwards, the witnesses agreed to come. It was a moment in time when all forces came together,” she added.

When asked about the challenges she faced during the case, she recalls the resistance from the public. “I used to get nuisance calls because people thought it was an attempt to persecute ‘war heroes’. But other than that, there were no challenges except for the pressure from various factions to solve the case,” she recalled.

As a young prosecutor, Mahindaratne was determined to put perpetrators behind bars. She reflects on the brutality of the crime to date. However, she advocates the need for accountability for conflict-related crimes. “A civilised society is expected to try and bring about accountability. The OMP mandate has been established to investigate these cases and, if possible, find these individuals if they are alive or if possible find the remains if they are dead and inform the families. Not a single family has been informed of their relatives, except in a few cases. But what about the rest?” she questioned in conclusion while underscoring the role of media in influencing public discourse on the state’s accountability process.

Mahindaratne was called to the bar in November 1990 and served at the AG’s Department from 1991-2001. She is also the first Sri Lankan woman to serve as a war crimes prosecutor at the United Nations War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague. While this case is an example of holding the military accountable for crimes committed during the war, it also reflects on the need for a political will to expedite such cases and bring about closure for victims affected by the war.