By Maneshka Borham.

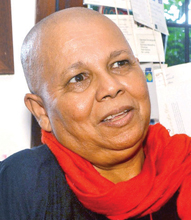

It has been 15 years and nine days since Sandya Ekneligoda last saw her husband, Prageeth Ekneligoda. On the day, 50-year-old Prageeth, a cartoonist and columnist for the news website Lanka e News, was at his home in Pannipitiya preparing to attend a Bodhi pooja for a friend.

“He realised that none of his white shirts had been washed. I told him there was a newly stitched white shirt meant for our eldest son, who was 15 at the time. He tried it on and it fit perfectly. He said how much our son had grown and seemed happy at the thought,” Sandya recalled.

With a busy day ahead, Prageeth had left home for the office unaware that this would be the last time he and Sandya would see each other. Neither of them could have imagined that their journey which began in the late 1980s would come to such an abrupt and tragic end.

“Prageeth and I first crossed paths at my workplace in Nugegoda, where he had been assigned to teach us how to design posters for our rights-based initiatives. I was introduced to him as a renowned artist, highly sought after for similar work,” she reminisced.

“Prageeth and I first crossed paths at my workplace in Nugegoda, where he had been assigned to teach us how to design posters for our rights-based initiatives. I was introduced to him as a renowned artist, highly sought after for similar work,” she reminisced.

The two quickly became close friends and remained so for years until Sandya finally gathered the courage to confess her love for him. “If I hadn’t, he would have never openly admitted that he had feelings for me,” she said laughingly.

Sandya had begun selling insurance plans to make ends meet after work had run dry for Prageeth after his first abduction attempt on August 27, 2009. But she recalls that on the day he went missing Prageeth had promised to help and support her to earn a living.

“He never wanted me to work. So when he told me that day, I finally felt like I had won him over. To win him over after many years together and lose him in such a heartbreaking way—it’s a tragedy, isn’t it?” she said.

Calls went unanswered

As the day drew to a close, an overwhelming sense of fear gripped Sandya. “I’ve never felt so afraid in my life as I did that day. I just knew they had finally got him. But I never imagined they would do something so brutal to him,” she said. As her calls to Prageeth went unanswered, her suspicions were proved true.

As the day drew to a close, an overwhelming sense of fear gripped Sandya. “I’ve never felt so afraid in my life as I did that day. I just knew they had finally got him. But I never imagined they would do something so brutal to him,” she said. As her calls to Prageeth went unanswered, her suspicions were proved true.

As her prolonged battle for justice unfolded amidst great hardships, in 2019 indictments were filed before the courts. It was the only case out of 125 complaints of crimes against journalists which took place between January 2005 and 2015 to finally reach the higher courts. As the case continued evidence emerged revealing the involvement of military intelligence in his enforced disappearance and ultimately tracing his final whereabouts.

According to Sandya, the legal battle has lumbered on with many obstacles and attempts to delay it. Today the case is being heard before a Special High Court Trial at Bar which was set up in August 2019.

“In August 2024, after a year’s delay, the court finally issued an order requesting records from a mobile service provider. At the next hearing, the court spent an entire day examining the relevant evidence. ‘It was the best court date of the case so far, and I felt satisfied. Everything went so well,” she said.

Sandya said the current environment within the court system is favourable for the case to move forward. Beyond the courtroom, a similar shift appears to be taking place. The recent appointment of SSP Shani Abeysekara as the Director of the Central Criminal Intelligence Analysis Bureau has renewed her sense of hope. Abeysekara previously led the Criminal Investigations Department (CID) during a period when crucial evidence in the case was uncovered by CID investigators.

“He is the best state official I have ever met. The first day I met him, Shani told me that he couldn’t bring my husband back, but he would find out the truth and reveal exactly what happened to him. He kept that promise. There is a clear interest to see this through. I believe they will make a genuine effort,” Sandya said.

“Hope is what keeps us going. Whether it becomes reality or not, we continue to hold on to it,” she added, having made every effort possible to obtain the justice seeks.

Since Prageeth’s disappearance, Sandya’s life has been a relentless struggle. She has shouldered the burden of financially supporting herself and her children while also navigating the emotional challenges faced by her youngest son, who battled depression after losing his father at a young age. Adding to her hardships, she has endured insults and scorn from supporters of the Rajapaksa clan, whom she has directly held responsible for her husband’s disappearance.

“I know that some have even taken advantage of me, and some may continue to do so. But I believe it’s just human nature, and I’ve made peace with it,” she said.

Sandya often wears a smile and maintains a stoic demeanour despite her many daily hardships. However, she admits that behind her smile lies a deep well of pain and sorrow that remains unseen by society.

“People may say I look well cared for and smile for the camera. But what about true happiness? That’s what they took away from us and our home,” she said. “We are alive, yet we live as though we are dead,” she said.

Media industry

According to her, mere commemorations by the media industry every January will not ensure justice is delivered to her or others who have suffered a similar fate. Justice, she insists, must not only be delivered to her but also to others who have suffered a similar fate. “Other children, like my own, have endured this tragic loss. The screams of journalist Taraki Sivaram’s daughter upon finding her father killed still echo in my ears. Justice must be served for them as well,” she said.

According to her, mere commemorations by the media industry every January will not ensure justice is delivered to her or others who have suffered a similar fate. Justice, she insists, must not only be delivered to her but also to others who have suffered a similar fate. “Other children, like my own, have endured this tragic loss. The screams of journalist Taraki Sivaram’s daughter upon finding her father killed still echo in my ears. Justice must be served for them as well,” she said.

“Commemorations are meaningful, but our efforts should not stop there. Many promises have been made over the years such as erecting a monument for slain journalists, yet none have come to fruition,” she said. “Can we truly offer any assurance to journalists about their future under these circumstances?” she asked. She said that the media industry should perhaps establish a mechanism that would provide support to the families of journalists navigating the courts and justice system.

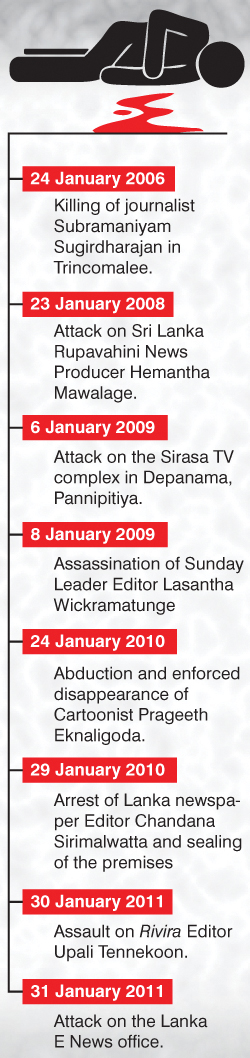

For journalists and the media industry in Sri Lanka, January, a month typically associated with new beginnings and hope, is a sombre reminder of darkness and tragedy. Chosen as the month of remembrance, January marks the untimely deaths of several prominent journalists and media figures, including cartoonist Prageeth Ekneligoda and Lasantha Wickrematunge, the Editor-in-Chief of the Sunday Leader. Their deaths, along with numerous others, enforced disappearances and brutal assaults continue to cast a long shadow over the industry, with justice remaining elusive.

As a result, media organisations once again took to the streets last week, honouring their fallen colleagues and demanding justice for their assassinations and enforced disappearances over the past three decades.

As a result, media organisations once again took to the streets last week, honouring their fallen colleagues and demanding justice for their assassinations and enforced disappearances over the past three decades.

According to the book, Martyrs, of the Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka, compiled by veteran journalist Seetha Ranjani, at least 114 journalists and media personnel have been killed since 1981. In addition to these tragic losses, many others have been forcibly disappeared, underscoring the grave risks faced by journalists in Sri Lanka’s recent past.

In 2016, then Minister of Law and Order, Sagala Ratnayake, presented a report to Parliament that the police had received 125 complaints of crimes against journalists between January 2005 and 2015. These included 13 assassinations, 87 assaults, 20 arrests, and attacks on five media organisations. However, to date, only one of these 125 incidents has been fully investigated and led to a case being filed. The 2015 Government also pledged compensation for the victims, but the promise was limited to a Cabinet paper which was never implemented.

On Wednesday, the Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association (SLWJA) held a silent protest in front of the Colombo Fort railway station to demand justice for journalists who have lost their lives over the years and for the many atrocities committed against them.

Powerful testament

During the protest, journalist Buwanaka S. Perera read out a poignant letter written by Raine Wickramatunge, the former wife of the late Sunday Leader Editor Lasantha Wickramatunge. The letter stands as a powerful testament to the trauma endured by the families of victims and the lasting impact of assassinations and enforced disappearances on them.

Raine goes on to describe how the trauma of losing their father permeated every aspect of the children’s lives from that moment onwards. She spoke of her own struggles to raise three children impacted by trauma.

Raine goes on to describe how the trauma of losing their father permeated every aspect of the children’s lives from that moment onwards. She spoke of her own struggles to raise three children impacted by trauma.

“As I watched my children grow, I was constantly reminded of the void left by their father’s absence, taken from us by senseless political violence. My children’s eyes, once bright with laughter, held a deep sadness. They struggled to understand why their father was torn from them and the pain of his loss echoed in their young hearts,” she said.

Raine also highlighted the need to break this cycle of violence and fear in Sri Lanka and her commitment to support any efforts for the sake of her children and others who endured similar circumstances.

Renewed hope

After decades of turmoil and violence, a sense of renewed hope emerged in the words of SLWJA President and seasoned industry professional, Duminda Sampath.

“We have, over the years, made numerous demands to successive Governments, including calling for a Presidential Commission of Inquiry and submitting petitions to seek justice for journalists. Yet, no justice has been delivered for those who were killed, abducted or assaulted. Today, there is renewed hope with the new Government. We urge them to enforce the law,” he said.

The Young Journalists Association’s Tharindu Jayawardena called for unity among Sri Lankan journalists, emphasizing the need for collective action to address the challenges facing the profession. “Journalists in Sri Lanka face numerous challenges, and finding solutions requires a united effort,” he said.

While the media community remains deeply divided not only across organisations but also along generational and linguistic lines—English, Sinhala and Tamil, according to Jayawardena, the media cannot solve these issues alone. He said it requires the support of trade unions, civil society organisations, and citizens. He reminded the attendees that Black January, which marks the struggles of journalists, should not be confined to one event a year. “We must continue to discuss these challenges every day, not just during this time,” he said, calling for a sustained effort to find meaningful solutions.

Pix by Sulochana Gamage and Sudath Nishantha