Kishali Pinto-Jayawardene.

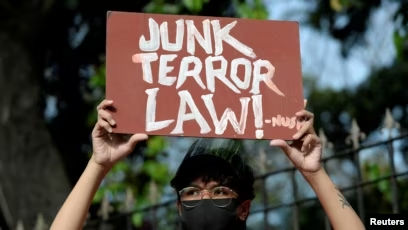

A grave danger raises its head once again with the recently gazetted Anti-Terrorism Act which seeks to replace the archaic Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). In many respects, the Bill reflects clauses of the highly critiqued Counter-Terrorism Act (CTA) that was proposed during the ‘yahapalana’ period.

This did not pass the seal of Parliament due to widespread public concern over its contents. Its challenge in the Supreme Court resulted in certain clauses being declared unconstitutional. The Determination of the Court (SC/SD 41-47/2018) was unremarkable in many aspects. Conservatively, the Court upheld the CTA proposal of an increased detention period of a suspect (48 hours in police custody).

The argument that this violated the constitutional guarantee to be speedily brought before a judge of the nearest competent court on arrest, (Article 13 (2)) was dismissed on the basis that the PTA already contained the provision for extended detention (78 hours, Section 7). Above all, the wider problem remains in regard to the vagueness and arbitrariness of definitions of the ‘offence of terrorism’ which went unexamined by the Court/were not canvassed before the judges in 2018.

Recasting penal offences as ‘terrorism’

Much of these concerns persist in the newest version of the Bill, earlier known as the CTA and resurrected from an inglorious burial place under a brand new name (‘Anti-Terrorism’) as placed before the Sri Lankan public. The central question then – and now – is the bringing over of ordinary criminal offences to be recast as ‘terrorist offences’ allowing the State far greater latitude in committing abuse of those who are arrested. There is much to be apprehensive therefore, particularly in the context of increased clashes between the State and trade unions, academics, students and civic protestors in recent months.

In the 2023 gazetted Bill, the ‘offence of terrorism’ (Clause 3 (1) and (2)) follow the earlier CTA definitions in the main. An illegal act or omission (murder, grievous hurt, hostage taking etc) is framed as a terrorist act if this, results in inter alia, ‘intimidating the public or section of the public’ or ‘wrongfully or unlawfully compelling the government of Sri Lanka, or any other government, or an international organization, to do or to abstain from doing any act.’

That same risk applies to any act which ‘unlawfully’ prevents any such government from functioning. Other clauses bring serious damage to property within the definition of terrorism if coupled with an ‘illegal act or omission.’ Meanwhile, the media continues to be put under special scrutiny. The Bill creates a category of ‘terrorist publications with media (print, electronic, web-based media etc) selling, circulating or distributing the same or having possession thereof, deeming to commit an offence.

“Coupled with broad definitions of what constitutes an ‘offence, ’ particularly the problematic primary offence of terrorism as vaguely worded in ‘wrongfully’ compelling the Government to do or abstain from doing any act,’ the risks for the media are clear.”

Problematic focus on the media

Alarmingly, intent to commit an offence thereto (direct/indirect) can be presumed as well as ‘recklessness’ in that regard. That applies similarly to ‘any person’ who ‘encourages’ terrorism’ by causing it to be published or publishing a statement to that effect. Additionally , the Bill defines ‘terrorism associated acts’ as having been committed by any person who, inter alia, ‘gathers’ or ‘supplies’ confidential information knowing or having reasonable grounds to believe that this will be used for an offence under the Act.

Coupled with broad definitions of what constitutes an ‘offence, ’ particularly the problematic primary offence of terrorism as vaguely worded in ‘wrongfully’ compelling the Government to do or abstain from doing any act,’ the risks for the media are clear. The ‘good faith’ defence (proviso to clause 9 of the Bill) offers no protection to legitimate journalistic activity. These are all different types of prohibited behaviour, often overlapping and reflecting a lack of clarity in their definitions as well as applications.

As observed previously in respect of similar phrasing in the CTA, these are legal abstracts that can swing one way or another depending on who the judge is sitting on the Bench. When inflammatory terms such as ‘terrorism’ or ‘national security’ are in issue, it requires a judge of tremendous mettle and prowess to stand up to the task. That is often not proved to be the case.

A reasonable rethink of the Bill

The proposed CTA will be part of the permanent law of the land, not an emergency regulation subject to challenge for fundamental rights violation in the Supreme Court. That by itself, merits anxious scrutiny of its scope and objectives in regard to which a fuller examination must be kept for another time. Suffice it to say that the Bill raises legitimate concerns as to its possible abuse for political ends.

Indeed, its open ended clauses as to what is ‘terrorism’ make a national security autocrat, whose species we have in our political establishment in many versions, dance in unholy glee. The 2023 Bill, as the 2018 proposed CTA also exemplified, may well be worse than the ancient PTA. At the time that the CTA was proposed, the opposition composed of Rajapaksa supporters opposed its contents with full force, arguing that this would result in a freezing of civil liberties.

Many political leaders opposing the draft CTA then – including the present Prime Minister – are now part of this Government. Levelling charges of hypocrisy against them is perhaps a waste of space, given their imperviousness to public criticism. Even so, it is wise to engage in a reasonable rethink of Sri Lanka’s Anti-Terrorism Bill as it now stands. Already this Government has wrapped the garb of anti-democratic defensiveness around itself as it meets dissent with more than minimum force.

If existing acute tensions between the State and the citizenry are not to be aggravated, the Bill should be stamped ‘handle with care.’ That is a reality that the European Union (EU) whose insistence as to the replacement of the PTA has led to all these drafts of new anti-terrorism/ counter-terrorism laws should be very much aware of.

(Excerpts from the article “On ‘best laws’ and the promises of the president” by Kishali Pinto Jayawardena, published in The Sunday Times on 26.03.23)