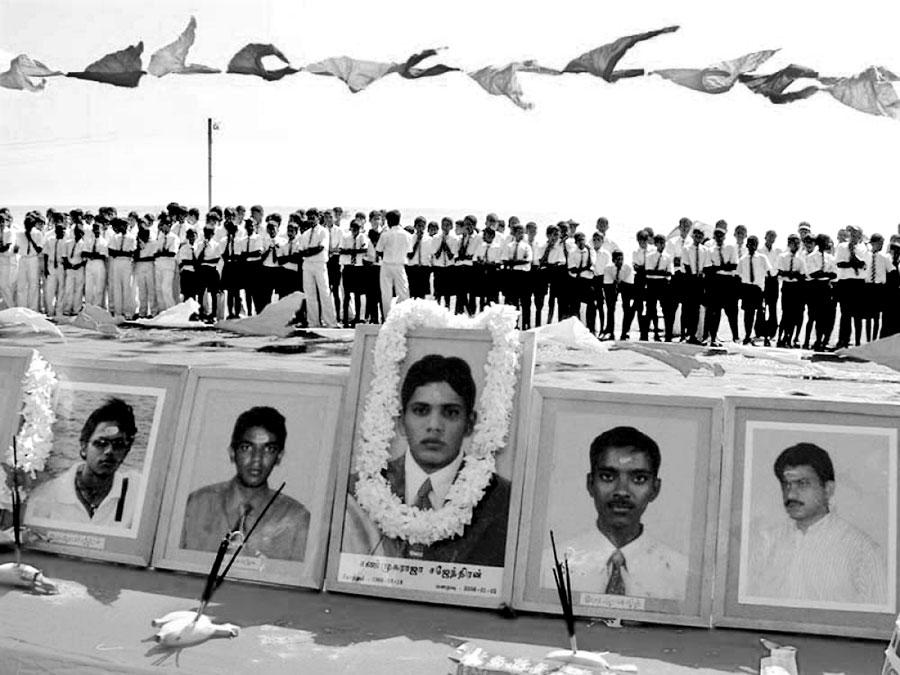

Let us not dissemble about the fact that the killing of five students of Tamil ethnicity in January 2006 was a cold blooded murder of innocents. The dead victims had been awaiting university entrance when they were mowed down. Bright, eager students, these were the best that Sri Lanka promised. No connection to ‘terrorist activities’ were established even though this was the immediate reaction by some state officers when public outrage arose over the killings.

That explanation was later discarded as it was without conceivable basis. Instead, the State stammered and stuttered when called to account for the casual murders of the teenagers.

A long agony ends with no justice

Five years ago, officers of the Special Task Force (STF) including an assistant superintendent of police (ASP) were arrested on ‘evidence available’ for this crime. Even measured against all the injustices of Sri Lanka’s spluttering criminal justice system, it was believed that, at least in this case, the responsible murderers would be brought to justice. Yet the acquittal of all the suspects several weeks ago, on the basis that there was no evidence against them, is an infamy.

Even as the freed suspects beamingly posed for photographs outside the court premises, the agony of the parents of these children who lost their children with no rhyme or reason, was compounded by the fact that no one was held responsible. Their pitiful state reflects the fact that the mills of Sri Lanka’s institutions of justice grind not only agonizingly slow but that they are also grind with a predilection that favours the State over innocents caught in the brutal toils of conflict.

This is one sad ending to a tale that had many miserable milestones. The 2006 Udalagama Commission of Inquiry, which tried to investigate these incidents was unceremoniously wound up even before it had completed its mandate. Family members of victims who gave testimony before the Commission despite not being afforded protection were bullied and tormented. In a pattern eerily reminiscent of what is happening now in regard to individuals of Muslims ethnicity after the Easter Sunday attacks by jihadists influenced by the Islamist State ideology, many section of the private media mercilessly harangued those who questioned as to why justice was not being done. Meanwhile, the Government denied that responsibility for these heinous acts was located in the chain of command at the time.

Markers of brutality through the ages

The killings of the five students stood out from the general brutality of that era. Together with the killings of aid workers of Action Contra L’Faim in Mutur that same year, these defined the Rajapaksa era in symbolising not a proportionate response of the protection of national security during the ongoing ethnic conflict with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam at the time but gross, barbaric acts. Similarly, the torture, rape and killing of a Sinhalese beauty queen Premawathie Manamperi defined the period of the first Sinhala youth uprising as much as the enforced disappearance of more than fifty Sinhalese schoolchildren in Embilipitiya defined the period of the second Sinhala youth uprising. The rape and murder of a Tamil schoolgirl Krishanthi Kumaraswamy along with members of her family defined the later years of the Kumaranatunga administration.

Yet, as has been observed previously in these column spaces, in the Manamperi, Embilipitiya and Krishanthi Kumaraswamy cases, the Sri Lankan justice system worked to some extent, albeit falteringly. In Manamperi, the Court issued a classic judicial warning to state agents who kill and then try to justify such killing on the defence of superior orders issued during times of emergency. In all the years that have passed, that commanding and authoritative tone set by those judges in that instance was never replicated to quite that same extent.

In the Kumaraswamy case and the Embilipitiya disappearances case, those responsible were brought to justice even though the reach of the law was not as bold as expected. In contrast, the cover-up in regard to the Mutur and Trincomalee executions persisted. The killings stood out in the public mind as characterised by the horrific acts of human brutality, practiced cold bloodedly and calculatedly on innocents. Perhaps it was that element of calculation that could not be countenanced. Civilian casualties caused by state killers in the heat of battle is certainly treated a tad differently, at least in the human consciousness, to targeted attacks such as these carried out by state agents.

Recovering a lost Sri Lankan humanity

As I wrote at the time, the Trincomalee and the Mutur killings remain important. They must be ceaselessly talked about. They are vital symbols of all the other thousands of lives lost during that period which remain unmarked and unnoticed. Agitating for justice in these cases symbolise a lost Sri Lankan humanity. Public opinion in Sri Lanka must recognize this important fact.

So as the Attorney General decides to pursue a fresh trial in this matter, that decision must be commended. Reportedly, the police have been ordered to trace key witnesses to the 2006 killings. However, merely identifying these witnesses will not be sufficient. An environment that is conducive for them to give evidence without fear or intimidation must be established. It is not practical to expect family members to give evidence from Sri Lankan missions overseas.

In that context, it is a question if Sri Lanka’s Victim and Witness Protection Act is lying in cold storage? It is precisely in cases like these that this Act must be employed to the fullest along with imaginative ways of obtaining testimony that protect the already traumatised family members.

What the past teaches us

There are lessons to learn from this case for us in the current environment as well. It is because of the fact that the members of one minority was treated with such mindless terror that distrust of the State increased to the point that there was very little confidence left. If the political winds that favour a Rajapaksa-return in one form or another increase in ferocity, we will face a possible decimation of civil liberties to an extent that will be unprecedented, even as assessed against the turbulent past.

The nation is now getting swept up in endless waves of virulent communalism. In that background, it is even more important to hold the line of justice and the law for this will be what ultimately holds Sri Lanka back from the brink.

In the absence of that, we may as well abandon the ‘good fight.’ecessary to curtail or to bring their violent activities under control.

(Sunday Times.)