Image: by SP Pushpakanthan.

Can the Office of Missing Persons provide answers in a country with the world’s second highest number of disappearances?

Sasikumar Ranginithevi can’t hide her tears as she looks at four faded photographs in her trembling hands.

Two brothers, a husband and her brother-in-law. They all fought for the Tamil Tigers. They all surrendered to the army. And they all disappeared.

Her hometown, Mullaitivu, is a city of the missing. Nestled on Sri Lanka’s northeast tip, this town was the front line in some of the bloodiest final battles of a 26-year civil war between the armed group, the Tamil Tigers, and government forces.

Sasikumar and hundreds of other Tamil families claim they handed over their loved ones – former combatants – to the military on a causeway near Mullaitivu in May 2009, just after the war ended.

“Many buses were lined up. Hundreds of them. I was seven months pregnant at the time. When I asked to go in the bus with my husband, the army commander refused,” she says.

Sasikumar was forced onto another bus and ended up at a refugee camp with her parents. She believed that her relatives would also be processed and brought to the camp.

But almost a decade later, she is still waiting, along with other relatives of former combatants who were herded onto buses and never came back.

I’m slowly telling him that his father is lost. Missing. It makes me cry inside … I don’t know whether he is dead or alive.

SASIKUMAR RANGINITHEVI

With most of the men of working age in her family gone, Sasikumar is struggling to survive as the sole breadwinner in her household.

“We have no peace in our lives. I have two children, I have parents and an older brother who was wounded in the war. My youngest son is nine years old. He keeps asking me where his father is. I keep telling him his father is in detention. Now I’m slowly telling him that his father is lost. Missing. It makes me cry inside. What can I tell my son? I don’t know whether he’s dead or alive,” she says.

|

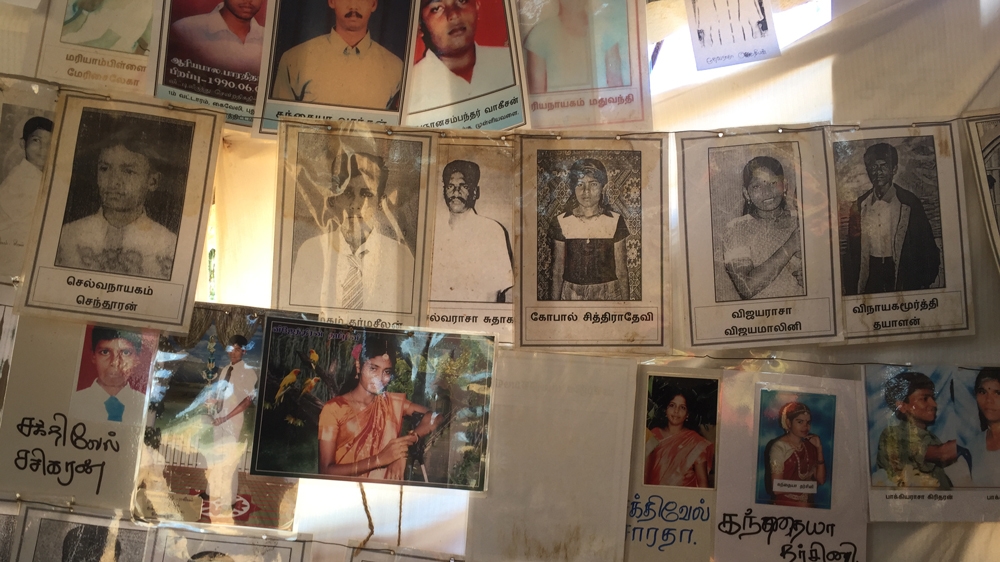

| Former fighters, children and civilians who disappeared during the 26-year civil war are still missing. [Al Jazeera] |

‘The army officer took the child from my arms’

Former fighters are not the only ones who disappeared in the chaos of the conflict. Children and civilians are also among the missing.

Sivakanthan Manchula’s eight-year-old son was wounded by a mortar shell in the final days of the war. Soldiers took him by helicopter to a hospital in another city for treatment.

“The army officer took the child from my arms,” she recalls. “They said they would bring him back when he was cured. They kept repeating that to us, even when they locked us up in the camp. He was only eight. If he died of the wound, I would have been able to accept the fact that he is no more.”

Like many whose loved ones went missing during the war, she reported her son’s disappearance to the United Nations and the Red Cross. But she admits she has very little evidence to prove what happened.

“How do they expect us to remember the faces of officers responsible? We were facing shelling, we had no food and water … we had to follow the soldier’s instructions like cows.”

Denial: ‘An exaggerated story’

At the time of these disappearances, former General Sarath Fonseka was Sri Lanka’s army chief. He says that all 215,000 Tamils who surrendered during the war were properly processed in the presence of international observers.

“During the last two weeks of the war, we had a good system where we had beautiful arrangements. I am 100 percent sure incidents of this nature never took place. People being taken in busloads and never returning – that is definitely an exaggerated story,” he says.

Many Tamil families of the missing refute these denials.

For the past year they have held daily vigils in Mullaitivu and four other towns across Sri Lanka. In the tents where they sit in the wind and the dust, photos of missing loved ones hang on the walls.

They’re furious with the authorities. When the government was elected in 2015, leaders promised to release the names of people held in custody, but have since refused to do so.

Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena has also been criticised for being slow to set up an Office of Missing Persons to trace the 60,000 Sri Lankans who disappeared in the last three decades. It took three years of deliberations before seven commissioners were appointed.

Lead commissioner, Saliya Pieris, a well-known human rights lawyer, says the Office of Missing Persons will have forensic experts, witness protection divisions and investigative powers. But he admits it will not have the power to prosecute guilty parties. The office can only refer suspects to the lawyer.

“I think the scepticism is natural,” Pieris says. “The only way we can get rid of this is through actions and by establishing a credible mechanism. If we promise people results overnight and the results are not forthcoming, people will lose faith. But we have to be objective, independent and impartial.”

|

| People were herded onto buses and never came back. [Al Jazeera] |

No public trust in the Office of Missing Persons

Critics remain doubtful that the new agency will help trace the missing. This is the 10th commission set up to investigate disappearances. None of the past efforts solved a single case.

In this divided country, the Office of Missing Persons has attracted criticism from various parties because the commissioners include a former army general, a family member of a disappeared person and human rights activists.

Dharsha Jegatheeswaran, a lawyer who works with families of the disappeared, says there isn’t a lot of public trust in the office.

“I think one of the reasons is that families weren’t consulted in the process,” says Jegatheeswaran, from the Adayaalam Centre for Policy Research.

“I think having a military representative was a huge blow to the families’ confidence … When military were often the perpetrators in disappearances that happened during the armed conflict, how can they feel confident going before somebody who is a military official and was part of the military during this period of the conflict?”

The military is also unhappy with the makeup of the commission.

While President Sirisena has said that war heroes would not be subject to scrutiny by the agency, Major General Uday Perera says many senior army officers are still not prepared to testify.

“When you have people who have been critical of the army as commissioners, I don’t think personally I would not like to go there and get humiliated. So it’s a matter of having credible, neutral people in the commission, rather than having activists and people who have been working for NGOs,” Perera says.

I think having a military representative was a huge blow to the families’ confidence … When military were often the perpetrators in disappearances that happened during the armed conflict, how can they feel confident going before somebody who is a military official and was part of the military during this period of the conflict?

DHARSHA JEGATHEESWARAN, LAWYER

Using abduction to silence government critics

Sri Lanka’s security forces aren’t only accused of wartime mass disappearances. They’ve been accused of abducting government critics to silence dissent. Trade unionists, journalists and human rights campaigners say they were targeted during and after the civil war.

Major General Perera, who was a chief of operations in northern Sri Lanka, denies the security forces have ever been involved in enforced disappearances,

“This is not a banana state,” he says. “If someone thinks that Sri Lanka can hide and keep a person in today’s context, I think he should go and see a psychiatrist.”

But his former boss, General Sarath Fonseka disagrees. Now a minister in Sri Lanka’s government, he says he is prepared to testify at the Missing Person’s Office that former President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s administration used abductions to silence their critics.

He alleges that former Defence Secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the former president’s brother, was the mastermind behind these abductions.

“I have very good tight control of the military. But there are other people like some in the police, some in intelligence agencies who prefer to please this man and join hands with him. Abductions were taking place Whoever did that, they did not do it during the process of their legitimate duties, outside the duties.”

In a statement, Gotabaya Rajapaksa denied these allegations.

“I very confidently take this opportunity to place on record that, during the war on terrorism mentioned, [the] government of Sri Lanka did not engage in any acts of alleged enforced disappearances and abductions as claimed by various scurrilous elements with vested political interest,” Rajapaksa said in a statement to Al Jazeera.

This is not a banana state … If someone thinks that Sri Lanka can hide and keep a person in today’s context, I think he should go and see a psychiatrist.

UDAY PERERA, MAJOR GENERAL

Systematic and widespread torture to instill fear

Earlier this year, Sri Lanka passed a law criminalising abductions. General Sarath Fonseka says abductions or enforced disappearances are a thing of the past.

But the International Truth and Justice Project, an advocacy group administered by the Foundation for Human Rights, has gathered testimony from 76 Tamil asylum seekers across Europe who allege they were abducted in the past three years.

It’s a claim backed up by London-based refugee lawyer, Kulasegaram Geetharhanan. He represents more than 100 clients who are claiming asylum in the UK because they fear their lives are in danger under Sri Lanka’s current regime. Geetharhanan says four of his clients claim they were tortured earlier this year.

“The torture is systematic and widespread. The purpose we can see is to instill fear in the Tamils, not to revolt again and at the same time, not to give evidence against the war crimes in 2009,” Geetharhanan says.

I think I could be abducted again if I went back … I will commit suicide if I’m forced back to Sri Lanka.

MILTON THUSANATHAN

Many of the men had relatives who fought for the Tamil Tigers. Milton Thusanathan, 20, alleges he was abducted and tortured in Mullaitivu by the security forces in 2016 and then again in 2017.

“I think I could be abducted again if I went back … I will commit suicide if I’m forced back to Sri Lanka,” he said.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA