DIGANA, Sri Lanka — When the Sri Lankan government temporarily blocked access to Facebook last month amid a wave of violence against Muslims, it seemed like a radical move against new technology.

But in fact, government officials saw it as a last resort. It came after Facebook ignored years of calls from both the government and civil society groups to control ethno-nationalist accounts that spread hate speech and incited violence before deadly anti-Muslim riots broke out this year, BuzzFeed News has found.

Government officials, researchers, and local NGOs say they have pleaded with Facebook representatives from as far back as 2013 to better enforce the company’s own rules against using the platform to call for violence or to target people for their ethnicity or religious affiliation. They repeatedly raised the issue with Facebook representatives in private meetings, by sharing in-depth research, and in public forums. The company, they say, did next to nothing in response.

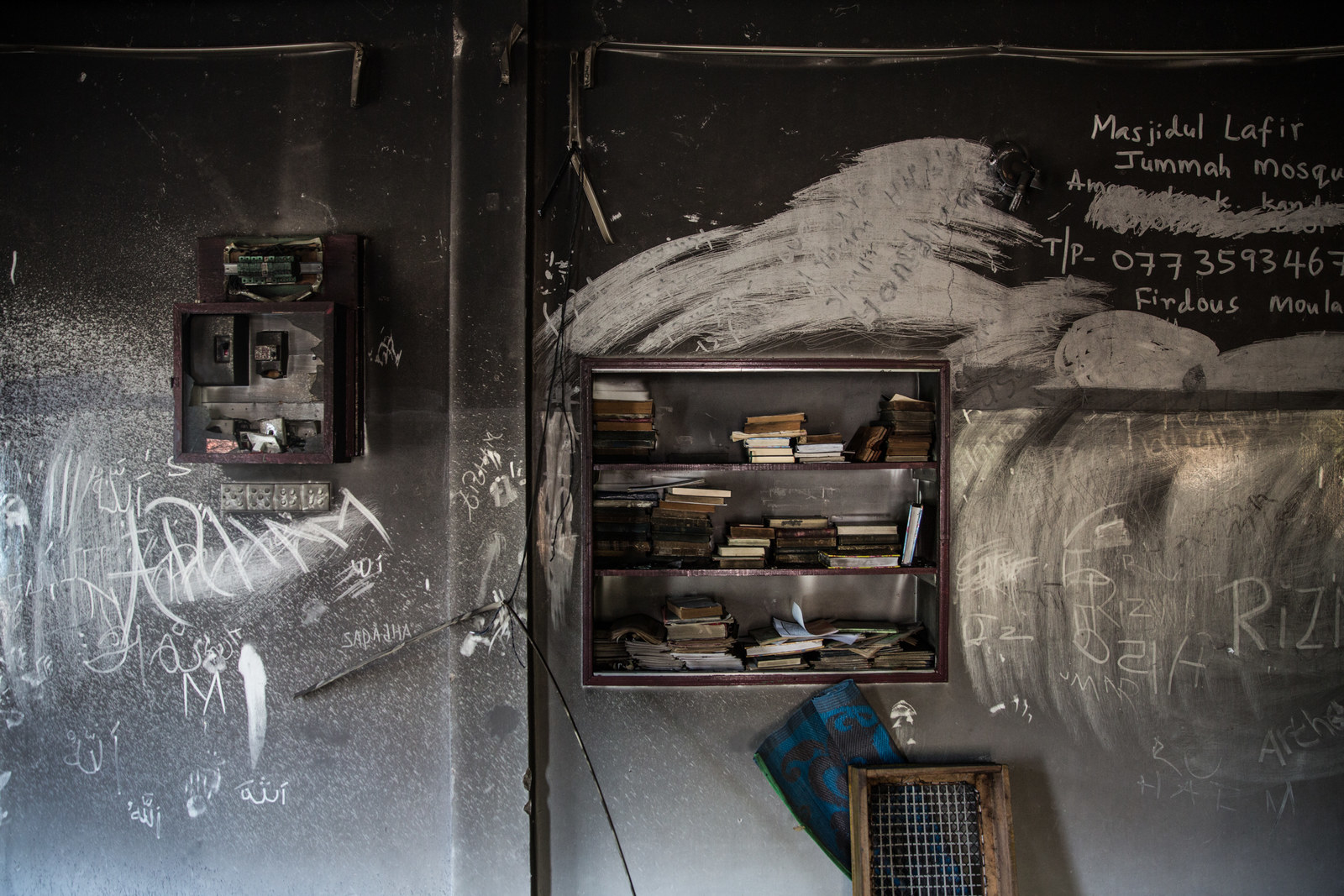

Ethnic tensions run deep in Sri Lanka, particularly between the majority Sinhala Buddhists and minority groups, and the country has seen a troubling rise in anti-Muslim hate groups and violence since the end of its decades-long civil war in 2009. Many of those hate groups spread their messages on Facebook. The problem came to a head in March when Buddhist mobs in central Sri Lanka burned down dozens of Muslim shops, homes, and places of worship. In response, the government blocked social media platforms including Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, in a decision it says was made to prevent the violence from spiraling further out of control. Facebook, officials said, couldn’t be relied on to respond to posts and videos inciting violence quickly enough.

“[Facebook] would go three or four months before making a response,” Harin Fernando, minister of telecommunications and digital infrastructure, told BuzzFeed News. “We were upset. In this incident, we had no alternative — we had to stop Facebook.”

The Centre for Policy Alternatives, a Sri Lankan think tank, also informed Facebook representatives about 20 ethno-nationalist hate groups targeting women and minorities nearly four years ago in a detailed research paper that contained dozens of links and screenshots, one of the paper’s authors told BuzzFeed News. At the end of March this year, 16 out of the 20 groups were still on Facebook.

Facebook is by far the most popular social media platform in Sri Lanka, and is a primary source of news for many Sri Lankans. But Sri Lanka has only about 6 million Facebook users — a drop in the ocean to Facebook. In short, Facebook is far more important to Sri Lanka than Sri Lanka is to Facebook.

“Excuse my language, but they’ve done fuck all about it,” said Sanjana Hattotuwa, a senior researcher at the Centre for Policy Alternatives who has lobbied Facebook for more than four years over the issue. “This is our frustration — and now it’s all too late.”

The Sinhala-speaking moderators Facebook does have are also effectively censoring Sinhala-language content for all of Sri Lanka, leaving many in the country wondering who these people are and what religious, political, and cultural biases they hold.

It’s not clear that the social media ban actually worked — in fact, Google searches for “VPN” spiked in Sri Lanka at the time, and extremists kept posting to Facebook along with government officials, intellectuals, and the media. It would have been better, internet freedom advocates said, for Facebook to have just enforced its rules on hate speech rather than have the government try to solve the problem by shutting off social media altogether.

“This block was about as useful as a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest,” said Yudhanjaya Wijeratne, an internet researcher who conducted an analysis of Facebook activity while it was meant to be inaccessible and found usage levels were roughly the same as in January and February.

But the block did make it much harder for families to communicate in a time of crisis, and it hampered the efforts of journalists and researchers who were trying to track the violence online. Many Sri Lankans, who have fresh memories of the hardline censorship of critical speech that characterized the civil war and the years immediately after its end, worried it would become a kind of digital martial law.

Almost immediately after Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp were blocked, the company dispatched a delegation of policy officials to the country to try to smooth things over with the government — officials and civil society groups said it was the highest-level Facebook delegation that had ever visited on official business.

“The decision to send a group of senior people came because the ban was on. It was not a good thing from any perspective, for Facebook or anyone else,” said Rohan Samarajiva, the former director general of telecommunications in Sri Lanka, who said he had helped arrange meetings for Facebook in the past. “They were coming to get the ban lifted. That was their agenda.”

Facebook did not directly reply when asked to respond to the claim that it has not enforced its standards on hate speech in Sri Lanka despite years of requests. A spokesperson told BuzzFeed News: “We have clear rules against hate speech and content that incites violence, and we remove such content as soon as we’re made aware of it. Our approach to hate speech has evolved over time and continues to change as we learn from our community, from experts in the field, and as technology enables us to operate more quickly and accurately.”

Hours after the Facebook delegation’s meetings in Sri Lanka, the government unblocked social media.

One of them was a man named Amith Weerasinghe. On a dirt road in the sleepy town of Digana, he turned his cell phone camera to selfie mode and recorded a message to his more than 150,000 Facebook followers. “The Muslims have completely taken over. We think we should have started this years ago,” he said in the video, posted on March 5. “If there are any of our [Sinhala] people in the Kandy and Digana areas, I urge you to wake up.”

That week, hundreds of men set fire to Muslim shops and homes in the area, killing two people.

Weerasinghe, who’s a Sinhala Buddhist, grew up in the area and went to a local school where Buddhist and Muslim children studied together, according to locals who remember him from his high school days in the late ’90s. It wasn’t until a few years ago that he became one of the country’s most vocal anti-Muslim campaigners on Facebook — a development that seemed utterly bizarre to his Muslim neighbors. BuzzFeed News was unable to reach Weerasinghe, who remains in custody, or his family. It is unclear whether he has retained a lawyer.

Weerasinghe built his following on Facebook through bigoted memes and videos. Sri Lankan police arrested him along with several suspected associates on March 8 for his role in inciting the violence. Facebook finally took his page down, as well as the March 5 video, but not before it garnered thousands of views and shares. (The video also stayed up on YouTube until April 6, when BuzzFeed News emailed a Google spokesperson about it.)

But Muslim residents of Digana said they regularly reported anti-Muslim posts and found that Facebook very rarely took them down. Several Sri Lankans interviewed by BuzzFeed News said they were part of informal social groups of hundreds of people who regularly shared abusive posts specifically to report them en masse to Facebook, believing this method was the only way to get the company’s content moderators to take them down. Facebook did not directly respond to a question about whether they were correct in this belief.

Her Muslim family was a middle-class success story, with a thriving furniture business that employed many workers who were Sinhala Buddhists. The Hilmys sent their children to local schools, where they studied and played with Buddhist kids. They loved their country, and though they knew there was anti-Muslim sentiment, they had always thought of violence as something that happened on the news, not to people like them.

Hilmy was devastated. Her father had lost his livelihood, and her family feared for their lives.

“I have lived in Sri Lanka all my life. This is my country. I don’t want to leave,” she said, adjusting her blue and orange headscarf. “But now we are thinking about it.”

There is no Muslim section of Hilmy’s town, which locals call “Eighth Mile Post.” Walking up the street from her father’s furniture store, Hilmy pointed out the Buddhist and Muslim businesses. Buddhist-owned fruit stands and convenience stores were open as usual; next to them, Muslim-owned shops stood as shells, destroyed by flames.

Weeks after the shop burned down, Hilmy’s grandmother passed away, and her father was hospitalized. “I can’t believe these racists gave us so much pain,” she said.

Just weeks before the riots around Digana, Muslim-owned businesses and a mosque were attacked in the eastern part of the country. The spark was an online rumor that a small Muslim restaurant in the town of Ampara was spiking its food with sterilization pills, targeting Sinhala Buddhists. At least five people were wounded in the violence, and the owner of the restaurant was forced to “confess” on video to adding the pills to the food.

The allegation sounds bizarre — after all, there is no pill in existence that can sterilize a person when added to food. But to close watchers of fake news in Sri Lanka, it came as no surprise. It fit right into a narrative that Buddhist nationalists have sought to push for years on social media: that the Muslims are trying to overtake the country’s population.

Over the years, many similar falsehoods have surfaced and circulated widely. One rumor claimed a Muslim-owned clothing chain called Fashion Bug was putting sterilization gel in undergarments meant for Sinhala women, despite the fact that there is no such thing as sterilization gel. (“If we had that kind of technology it would be a major breakthrough,” joked Hilmy’s cousin, Nushrath Mansoor.)

Part of the problem is that hate groups have learned how to work around Facebook’s rules, knowing their followers will read between the lines. Amid the spread of false rumors about Muslim businesses trying to sterilize Sinhala women, for instance, a video posted on Facebookin February showed a woman cutting into a bra to find tiny gel blobs in the padding.

“What we see is that perpetrators are manipulating Facebook’s reporting guidelines. They know what the guidelines are, and are taking lots of different measures to avoid coming against them,” said Sachini Perera, a feminist activist who focuses on technology and women’s rights.

Immediately before and during the riots, extremists on Facebook were saying Muslims should be killed like dogs, posting detailed instructions on making petrol bombs, and even agitating for armed conflict, according to screenshots collected by Jeevanee Kariyawasam, a lawyer and politician. The posts were later taken down.

It’s clear that these posts can be dangerous. After Weerasinghe filmed his video in Digana, the mosque Shaheed attends in the town was burned to the ground by rioters.

Fernando said that Facebook had agreed to open direct communications with two new points of contact within the government, one under his own Ministry of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure and another under the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission. Personnel there would work to find and flag hate speech to Facebook’s own content moderators, even translating from Sinhala or Tamil to English.

That’s a problem because many people in Sri Lanka don’t trust the government to treat minority groups fairly. Minority rights advocates in Sri Lanka have criticized the government for failing to prevent racial tensions from escalating this year, saying blocking social media was a band-aid fix for a much bigger problem. Two people in Digana showed BuzzFeed News cell phone videos in which local police stood idly by as mobs flooded the town’s narrow streets — an indication, they believed, of the indifference of government authorities.

“We are duty-bound to protect minorities and children,” said Sudarshana Gunawardana, director general of the Department of Government Information. “If the government alone is trying to do this monitoring, it may lead to excesses, and people who monitor might not be able to differentiate between hate speech and dissent. We don’t want that to happen.”

Facebook did not directly respond to a question about whether it is establishing such a mechanism with Sri Lankan authorities, but a spokesperson said it is working with the government as well as civil society to “learn more about local context and changing language, and exploring the use of technology to help.”

The spokesperson added: “There is always more we can do, and we’re committed to having the right policies, products, people and partnerships in place to help keep our community in Sri Lanka safe.”

Several civil society activists who were briefed by Facebook about the visit also said the company had not agreed to take down any speech outside of its own community standards, though the company has not released its own version of events.

Facebook is secretive about the exact makeup of its community operations team, which is in charge of user support, but a cheery recruitment video posted on YouTube offers a glimpse into how the company sees it. The video, set in the company’s Dublin offices, presents the team as a kind of mini United Nations, showing the office draped with different countries’ flags and a host of employees speaking English with different accents.

Facebook has said it’s investing in building the team, including hiring more people proficient in world languages. It said over 15,000 people work in different parts of the world for the company to combat harassment, fake accounts, and other abuses, though it’s likely that a portion of those employees work for outside contractors.

“Here in Dublin alone, we have so many nationalities and such a broad range of cultures,” says one Facebook employee in the video. “The scale at which we operate, in a lot of senses, has never been done before.”

Hattotuwa’s think tank has been tracking hate speech on social media since 2013, putting together several research papers and lobbying the government on the issue.

The organization’s papers cited and linked to Facebook pages spreading sterilization conspiracy theories and depicting Muslims as an enemy population. Years later, the majority of those pages remain on Facebook. One of them, called Helaya Sri Lanka, posted on Aug. 10, 2013, “The Muslims have taken up arms to kill the Sinhalese. Are you going to stay silent any longer? The battle begins now.”

Relatively few organizations were researching the phenomenon of hate speech on social media when Hattotuwa first became interested in it, and his work could have been a warning to Facebook, signaling problems it would later face in places like Myanmar. But in Hattotuwa’s telling, his findings had little impact on Facebook’s approach.

Hattotuwa has told Facebook about his organization’s research at every opportunity, sending the company the papers and even confronting Facebook representatives at events. In November, for instance, Facebook representatives came from New Delhi to give a largely technical presentation about new projects they were launching, including a version of WhatsApp tailored for businesses. They wanted Hattotuwa’s input on how they could teach Sri Lanka’s politicians to make more effective use of the platform to engage with constituents.

“They wanted to make Facebook part and parcel of Sri Lanka’s political discourse,” Hattotuwa said. The representatives listened when he told them they needed to hire more people to moderate abusive content in Sinhala language, he said, and they promised to look into it. But later the company stopped responding.

Other officials and civil society advocates, including Perera, the researcher, and Raisa Wickrematunge, editor at the civic media initiative Groundviews, said they have confronted Facebook representatives in similar fashion.

Wickrematunge recalled meeting a representative from Facebook at a conference on online disinformation at Stanford in 2017. At a breakout session, she brought up the issues in Sri Lanka, urging the company to hire more content moderators who were proficient in Sinhala and who could respond to content abusing women and minorities quickly, before a crisis hit. The Facebook representative listened politely and gave Wickrematunge her card, she said.

Wickrematunge said the question-and-answer session became combative, with journalists from other developing countries like Zimbabwe and Colombia demanding answers from the Facebook representative about similar problems. But Wickrematunge tried to keep things friendly. She hoped that would make Facebook more amenable to hearing her out.

“I was wondering if you could help us in terms of the issue I raised pertaining to language — given that at times there are photos that are often uploaded with derogatory comments in Sinhalese, which aren’t taken down due to the language barrier, and because the context isn’t clear,” she wrote in an email about a week later, which she shared with BuzzFeed News. “Would it be possible for someone familiar with the language and context to act as a rapid responder here, similar to in Bangladesh and other countries? And how would the process around that work? Do let me know.”

No one from Facebook ever responded, she said.

Perera said she had interviewed women who had reported Facebook harassment to CERT, the Sri Lankan advisory body on cybersecurity. CERT had told them to report their problems to Facebook instead.

“Then you’re stuck in a loop and you’re not getting the kind of support you need,” she said.

“They need much better regulation,” said the internet researcher Wijeratne, who was involved in recent discussions with Facebook officials on the problems in Sri Lanka. “They have their community standards and they need to implement them. I don’t think the government should be involved in Facebook — I think that’s dangerous.” ●

Andre Malerba for BuzzFeed New

Courtesy BuzzFeed.