IN JULY 2012 a man calling himself Sam Bacile posted a short video on YouTube. It showed the Prophet Muhammad bedding various women, taking part in gory battles and declaring: “Every non-Muslim is an infidel. Their lands, their women, their children are our spoils.”

The film was, as Salman Rushdie, a British author, later put it, “crap”. “The Innocence of Muslims” could have remained forever obscure, had someone not dubbed it into Arabic and reposted it in September that year. An Egyptian chat-show host denounced it and before long, this short, crap film was sparking riots across the Muslim world—and beyond. A group linked to al-Qaeda murdered America’s ambassador in Libya. Protests erupted in Afghanistan, Australia, Britain, France and India. Pakistan’s railways minister offered a $100,000 bounty to whoever killed the film-maker—and was not sacked. By the end of the month at least 50 people had died.

Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton condemned both the video and the reaction to it. General Martin Dempsey, then chairman of America’s joint chiefs of staff, contacted Terry Jones, a pastor in Florida who had previously burned a Koran in public, and asked him not to promote the video.

“Consider for a moment: the most senior officer of the mightiest armed forces the world has ever seen feels it necessary to contact some backwoods Florida pastor to beg him not to promote a 13-minute D-movie YouTube upload. Such are the power asymmetries in this connected world,” writes Timothy Garton Ash in “Free Speech”, a fine new book on the subject. The story of “The Innocence of Muslims” illustrates several points about how freedom of speech has evolved in recent years.

First, social media make it easy for anyone to publish anything to a potentially global audience. This is a huge boost for freedom of speech, and has led to a vast increase in the volume of material published. But when words and pictures move so rapidly across borders, conflict often results. Different nations have different notions of what may and may not be said. If the pseudonymous Mr Bacile had made his video in the early 1990s, Muslims far away would probably never have heard of it, and no one would have died.

Second, technology firms are having to grapple with horribly complex decisions about censorship. The big global ones such as Facebook and Twitter aspire to be politically neutral, but do not permit “hate speech” or obscenity on their platforms. In America the White House asked Google, which owns YouTube, to “review” whether “The Innocence of Muslims” violated YouTube’s guidelines against hate speech. The company decided that it did not, since it attacked a religion (ie, a set of ideas) rather than the people who held those beliefs. The White House did not force Google to censor the video; indeed, thanks to America’s constitutional guarantee of free speech, it had no legal power to do so.

In other countries, however, governments have far more power to silence speech. At least 21 asked Google to block or consider blocking the video. In countries where YouTube has a legal presence and a local version, such as India, Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, it complied. In countries where it did not have a legal presence, it refused. Some governments, such as Pakistan’s and Bangladesh’s, responded by blocking YouTube completely.

Shut up or I’ll kill you

The third recent change is that, whereas the threats to free speech used to come almost entirely from governments, now non-state actors are nearly as intimidating. In the Mexican state of Veracruz, for example, at least 17 journalists have disappeared or been murdered since 2010, presumably by drug-traffickers. The gangs’ reach is long: one journalist fled to Mexico City, where he was tracked down and butchered. And their methods are brutal: in February the body of a reporter was found dumped by the roadside, handcuffed, half-naked and with a plastic bag over her head.

Globally, the willingness of some Muslims to murder people they think have insulted the Prophet has chilled discussion of one of the world’s great religions—even in places where Muslims are a minority, such as Europe. Radical Islamists are attempting to enforce a global speech code, in which frank discussion of their beliefs is punishable by death.

This began in 1989 with a threat from a state: Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s leader, issued a fatwa condemning Mr Rushdie to death for a novel that he thought insulted Islam. He invited devout Muslims everywhere to carry out the sentence. It was almost certainly one of them who murdered Mr Rushdie’s Japanese translator in 1991, though the killer was never caught.

Since then, the notion that individual Muslims have a duty to defend their faith by assassinating its critics has spread. Most Muslims are peaceful, but it takes only a few to enforce what Mr Garton Ash calls “the assassin’s veto”. The Islamist who murdered Theo Van Gogh, a Dutch filmmaker, for making a film about the abuse of Muslim women, said he could not live “in any country where free speech is allowed”. In 2015 two gunmen stormed the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a French paper which had published cartoons of Muhammad, killing 12 people. Many speakers and writers across the world are terrified of offending Islamists. A satirical musical called “The Book of Mormon” is an international hit; no theatre would dare stage a similar treatment of the Koran.

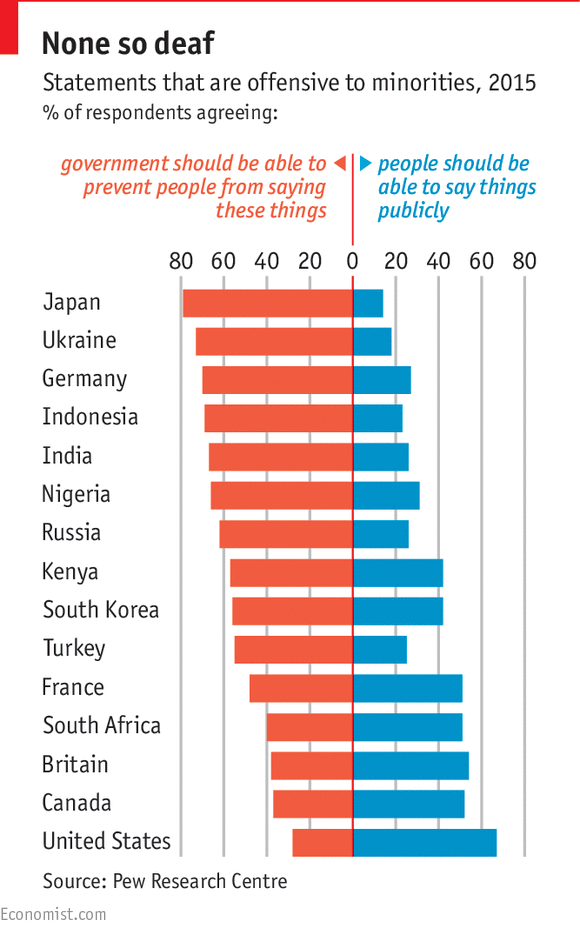

Islamist intimidation is the most extreme example of a broader, and worrying, trend. From the mosques of Cairo to the classrooms at Yale, all sorts of people and groups are claiming a right not to be offended. This is quite different from believing that people should, in general, be polite. A right not to be offended implies a power to police other people’s speech. “Taking offence has never been easier, or indeed more popular,” observes Flemming Rose, a former editor at Jyllands-Posten, a Danish paper. He should know. After his paper published cartoons of Muhammad in 2005, at least 200 people died.

The zealots who hack atheists to death in Bangladesh (see article) are far more frightening than the American students who shout down speakers with whom they disagree (see article). But they are on the same spectrum: both use a subjective definition of “offensive” to suppress debate. They may do this by disrupting speeches they object to; Mr Garton Ash calls this “the heckler’s veto”. Or they may enlist the power of the state to silence speakers who offend them. Politicians have gleefully jumped on the bandwagon, and are increasingly using laws against “hate speech” to punish dissidents.

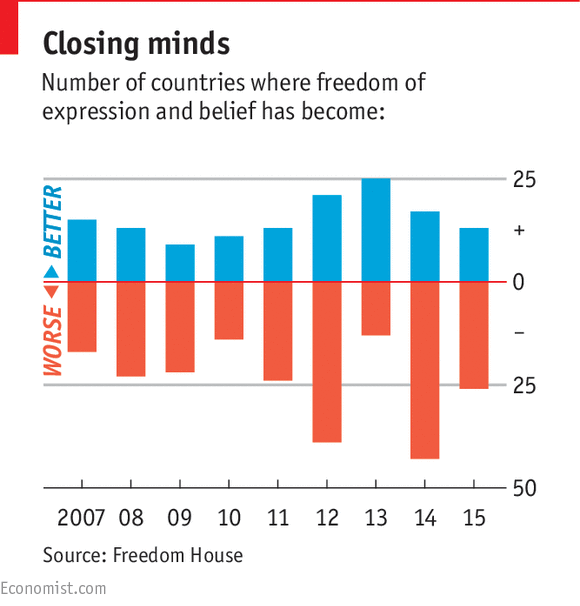

This article will argue that free speech is in retreat. Granted, technology has given millions a megaphone, and speaking out is easier than it was during the cold war, when most people lived under authoritarian states. But in the past few years restrictions on what people can say or write have grown more onerous.

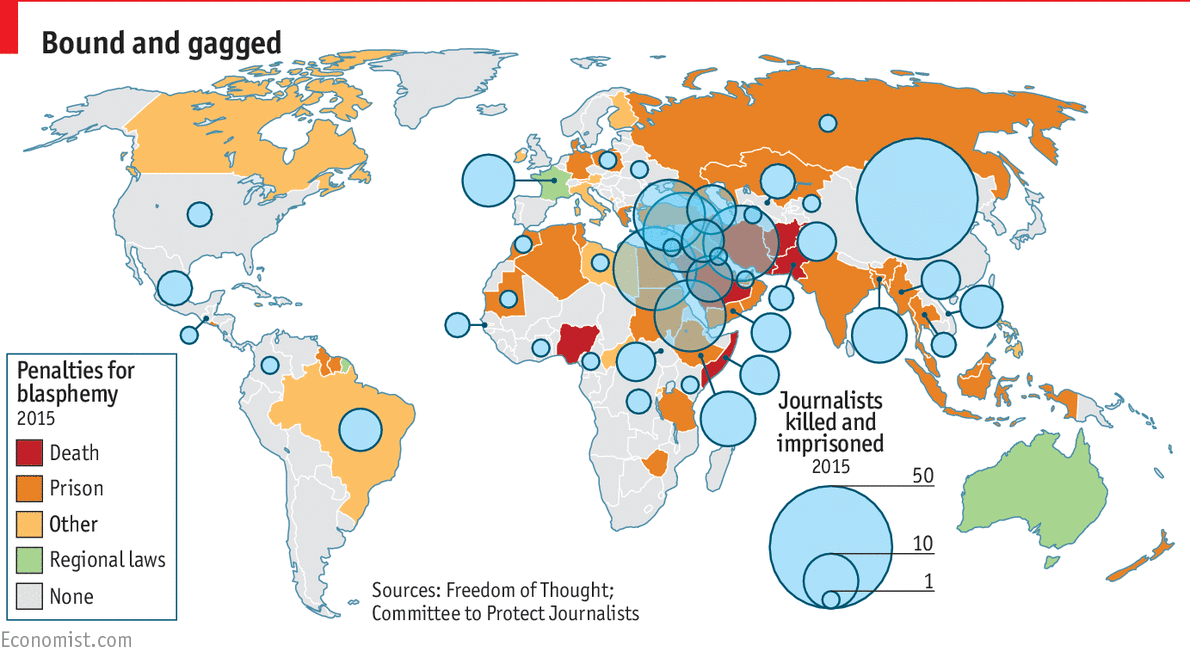

Freedom House, an American think-tank, compiles an annual index of freedom of expression. This “declined to its lowest point in 12 years in 2015, as political, criminal and terrorist forces sought to co-opt or silence the media in their broader struggle for power”. The share of the world’s populace living in countries with a free press fell from 38% in 2005 to 31% in 2015; the share who had to make do with only “partly free” media rose from 28% to 36%. Other watchdogs are similarly glum. Reporters Without Borders’ global index of press freedom has declined by 14% since 2013.

Uncle Xi is watching you

Among big countries, China scores worst. Speech there has hardly ever been free. Under Mao Zedong, the slightest whisper of dissent was savagely punished. After he died in 1976, people were gradually allowed more freedom to criticise the government, so long as they did not challenge the party’s monopoly on power. Digital technology accelerated this process. By the time Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, hundreds of millions of Chinese were happily sharing their views on social media.

Mr Xi found this unnerving, so he cracked down. China’s thousands of censors have ramped up efforts to block subversive online messages. Hundreds of lawyers and activists have been harassed or jailed. Liberal debate on university campuses has been suppressed (students and teachers are being urged to pay more attention to Marxism-Leninism). According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, a watchdog in New York, at least 49 journalists were in prison in China in December 2015. In April that year Gao Yu, an elderly reporter, was given a stiff sentence for “leaking state secrets”—namely, a party document warning against “Western” ideas such as media freedom.

Many Chinese stay one step ahead of the censors, using software to jump over the Great Firewall of China and reach foreign websites. Nonetheless, Mr Xi’s crackdown will surely weaken his country. If information does not flow freely, it is hard to innovate or make sound decisions. In recent months, as the stockmarket has wobbled, the party has pressed economists to put on a happy face. Analysts who predict turmoil are warned to shut up or recant. How policymakers are to understand the economy when no one is allowed to discuss it honestly is anyone’s guess.

In China the state is the source of nearly all censorship. Private organisations play a role, but largely at the party’s behest or to avoid upsetting it. Baidu, the Chinese answer to Google, blocks potentially subversive search results. Google refuses to do so, and is therefore unable to operate in China. Wikipedia, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are also blocked.

In the Muslim world, by contrast, speech is under attack from state and non-state actors in roughly equal measure. The assassin’s veto is exercised keenly in such places as Bangladesh, Iraq, Nigeria, Somalia and Syria. In several Arab countries, after a brief flowering of free debate during the Arab spring, regimes even more repressive than the old ones have taken charge.

Consider Egypt, the Arab world’s most populous country. In 2011 mass protests led to the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak, a dictator. For a while, Egyptians were free to say what they wanted. But a Muslim Brotherhood government elected in 2012 curbed secular speech, and the coup that toppled it in 2013 made matters worse, says Muhammad Abdel-Salam of the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, an Egyptian pressure group.

Media outlets supportive of the Muslim Brotherhood, which Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi, Egypt’s present ruler, has branded a terrorist organisation, have been closed down. A new law makes it illegal for journalists to publish “untrue news or data” (ie, anything that contradicts the official line). “Don’t listen to anyone but me,” warned Mr Sisi in February. “I am dead serious.”

Foreign reporters have been branded as spies and run out of the country. Local reporters have it much worse. Mahmoud Abou Zeid, a photographer, was arrested while snapping the authorities gunning down Islamist protesters in 2013. He has been in jail ever since, accused of “damaging national unity”. He has been beaten, tortured and denied medical care.

On May 7th an Egyptian court recommended the death penalty for three journalists it accuses of spying. They deny the charges; one says he is being punished for publishing an embarrassing leaked document. The regime is incompetent as well as oppressive: in May an internal memo on how to squash the press was accidentally sent to the press.

Claiming to act as Egypt’s father, Mr Sisi is anxious that his children not be exposed to adult material. Saucy writers are jailed. Rights groups say that the number of prosecutions involving “contempt of religion” and “debauchery” (often used to prosecute homosexuals) are at all-time highs.

The authorities mine Facebook and Twitter for information on future protests, which are illegal, and for evidence against dissidents. Amr Nohan, a student, was sentenced to three years in prison for posting a photo of Mr Sisi with Mickey Mouse ears. Others are locked up for running websites without a licence. Asked why someone would need one, an assistant minister said: “You cannot drive without a licence. You cannot administer a website without a licence. It’s the same.”

All over the world, the spread of organised violence has prompted governments to curb speech they think may foster terrorism. Even in liberal democracies they are starting to punish not only those who deliberately incite violence, but also speakers who are merely intemperate or shocking.

In February, for example, two puppeteers were arrested in Madrid. Their show, “The Witch and Don Cristóbal”, was provocative: a nun was stabbed by a crucifix; a judge was hanged with a noose. What upset the police, however, was a scene where a puppet policeman accused a witch of supporting terrorism and shoved a sign reading “Up Alk-ETA” (a reference to al-Qaeda and ETA, a Basque separatist group) into her hands. The puppeteers are now awaiting trial and face up to three years in prison for “glorifying terrorism”. They are said to be surprised.

In much of Europe anti-terror laws are being used more zealously than before. This is partly because governments are more scared of terrorism, but also because they have started to police social media, where words that might reveal extremist sympathies are easily searchable. ETA laid down its arms in 2011; yet the number of Spaniards accused of glorifying terrorism has risen fivefold since then.

France criminalised “the defence of terrorism” in 2014 and has enforced the law more aggressively since the attacks on Paris last year. In the days after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, prosecutors opened 69 cases for “defence of terrorism”. One man was sentenced to a year in prison for shouting in the street: “I’m proud to be Muslim. I don’t like Charlie. They were right to do it.”

Many countries have introduced or revived laws against “hate speech” that are often broad and vague. In France Brigitte Bardot, an actress, has been convicted five times of incitement to racial hatred because, as an animal lover, she complains about halal slaughter methods. In India section 153A of the criminal code, which was introduced under British rule, punishes with up to three years in jail those who promote disharmony “on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community or any other ground whatsoever”.

Such laws are handy tools for those in power to harass their enemies. And far from promoting harmony between different groups, they encourage them to file charges against each other. This is especially dangerous when cynical politicians get involved. Those who rely on votes from a certain group often find it useful to demand the punishment of someone who has allegedly insulted its members, especially just before an election. For example, when an Indian intellectual called Ashis Nandy made a subtle point about lower castes and corruption at a literary festival in 2013, local politicians professed outrage and he was charged under India’s “Prevention of Atrocities Act”.

Many countries still have laws against blasphemy, including 14 in Europe. Rita Maestre, a left-wing Spanish politician, was convicted in March of insulting religious feelings during a protest in a Catholic chapel, during which women bared their chests, kissed one another and allegedly shouted “Get your rosaries out of my ovaries!” She was fined €4,320 ($4,812).

Islamic governments such as those of Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, which punish blasphemy against Islam ferociously, are keen for a ban on insulting religion to be written into international law. They argue that this is a natural extension of the Western concept of “hate speech”. Some Western authorities agree: Danish police in February filed preliminary charges against a man for burning a Koran, thus, in effect, reviving a law against blasphemy that had not been used to convict anyone since 1946.

Europe is full of archaic laws that criminalise certain kinds of political speech. It is a crime to insult the “honour” of the state in nine EU countries; to insult state symbols such as flags in 16; and to say offensive things about government bodies in 13. Libel can be criminal in 23 EU states. Bulgaria, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Portugal all punish it more harshly when it is directed at public officials. Some of these laws are seldom invoked, and France got rid of its law against insulting the head of state in 2013, five years after a protester was arrested for waving a banner that said “Piss off, you jerk” to President Nicolas Sarkozy. (The banner was merely quoting Mr Sarkozy, who had said the same thing to a different protester.)

In Germany, however, Jan Böhmermann, a comedian, is awaiting charges for insulting a foreign head of state, after he recited a scurrilous poem about Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the president of Turkey, and some frisky livestock. Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, is now considering repealing the law. Poland and Portugal, among others, have similar laws against insulting foreign heads of state. Icelanders can in theory get six years in prison for it.

“These are the kinds of provisions we are constantly fighting in countries where freedom of expression is not as open,” says Scott Griffen of the International Press Institute. Autocratic regimes are quick to borrow excuses from the West for cracking down on free speech. China and Russia accuse dissidents of “promoting terrorism”, “endangering national security” or “inciting ethnic hatred”. This can mean simply expressing sympathy for Tibetans on social media—for which Pu Zhiqiang, a Chinese lawyer, was locked up for 19 months. Rwanda’s government, borrowing from European laws against Holocaust denial, brands its opponents as apologists for the 1994 genocide and silences them. Europeans may laugh at Thailand’s lèse-majesté laws—a Thai was recently prosecuted for being sarcastic about the king’s dog. But when 13 European democracies also have laws against insulting the head of state, it is hard to avoid charges of hypocrisy.

A determined regime can usually think of ways to muzzle a voice that annoys it. Khadija Ismayilova, a journalist in Azerbaijan who revealed scandalous details about the ruling family’s wealth, received photos in the post in 2012 showing her having sex with her boyfriend. A secret camera had been installed in her flat. A letter threatened to post the video online if she did not stop investigating corruption. She refused, and it was posted on a website purporting to belong to an opposition party. When this did not silence Ms Ismayilova, she was charged with tax evasion and driving a colleague to attempt suicide. No evidence supported these charges, but she was sentenced to seven years in jail.

However, after an appeal to international law and a campaign to persuade donors, such as America, to take notice, Ms Ismayilova was released on May 25th. Even oppressive governments can sometimes be shamed into behaving better.