by Prof. V. Suryanarayan–

In 1948, soon after independence, the Government of India appointed a Commission under the Chairmanship of Dr. S. Radhakrishnan to enquire into the prevalent higher education system and to make recommendations so that the Indian Universities could face the challenges of the post-independence era. One of the distinguished members of that Commission was Dr. Arthur E Morgan, the first Chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the United States. In the course of the enquiry the Commission visited Visva Bharathi, the well known educational institution founded by Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore. The Vice Chancellor had organized a public meeting so that the members of the Commission could exchange views with the general public. Among the audience were few members of the Santhal tribe. Arthur Morgan asked the Vice Chancellor as to what extent the University has been able to enrich the lives of the Adivasis in whose midst it was situated.

Gandhiji and long before him Tolstoy subscribed to the same idea. In fact when the Indian National Congress assumed power in various states following the electoral victory in the elections held under the Government of India Act of 1935, the first advice that Gandhiji gave to them was to introduce universal education through the medium of some craft.

Prof. Ramu Manivannan is a strong advocate of this noble principle of higher education. Since assuming the Chairmanship of the Department of Politics and Public Administration Ramu has revamped and modernized the syllabus and teaching curriculum. Today the students are taught and scholars do research on issues of human rights, ongoing democratic struggles in South Asia and refugee issues. Ramu is not an ivory tower intellectual; he and his students are actively involved with movements for peace and justice in India and its neighbourhood. This edited volume is a testimony to the commitment of Ramu, his colleagues and students to understand and sensitize the public to the momentous developments taking place in India’s southern neighbourhood.

This edited volume is a result of collective effort. Special mention should be made of the untiring efforts of Dr. Ashik Bonofer who teaches Political Science in Madras Christian College. Dr. Bonofer is a scholar of great promise who is specialising in the political developments in Sri Lanka and Maldives. Mention should also be made of the rigorous work put in by students and research scholars – Parthiban, Divya, Radhika, Santosh, Priya, Nithya, Kalaiarasi and Karuna.

The book is divided into two sections. In the first part Prof. Ramu Manivannan has provided a succinct analysis of the political developments in Sri Lanka and the many acts of discrimination against the Tamils. He then proceeds to highlight how the war against the Tamils degenerated into a savage war against Tamil civilians. The second section includes eye witness accounts of the war, the report of the University Teachers of Human Rights (UTHR), submissions made to the UN Secretary General’s panel of experts, the UN Report, the Reports of the International Crisis Group, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Report of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) which lists out details of continuing military occupation and ongoing land colonization in the traditional Tamil homeland. The volume is first of its kind, which combines a brilliant analysis of the Fourth Eelam War with documentation to substantiate the arguments. This magnum opus is a good reference work for all students of contemporary South Asia.

In the introductory chapters, Prof. Ramu Manivannan has raised a very pertinent question – the contradiction between the principle of absolute sovereignty of the state and the global Responsibility to Protect (R2P). During recent years R2P is rapidly gaining ground as an important axiom in International Humanitarian Law. It is a simple, but at the same time, a very powerful idea. At present, the primary responsibility of protecting the people against mass atrocities and genocide lies with the State. State sovereignty implies responsibility to protect, not to kill. But when the State is unable or unwilling to abide by this primary responsibility, it is the duty of the international community to step in and uphold this principle. The primary tools of the international community are persuasion and support. But when this fails the international community must think in terms of international intervention to prevent catastrophe and genocide. R2P was unanimously adopted by the UN General Assembly in the world summit at 2005. But much more remains to be done before it becomes a universal axiom. The brain behind the R2P is Gareth Evans, the former Australian Foreign Minister, who played a stellar role in bringing peace to war torn Cambodia.

It would have been a valuable addition if Prof. Ramu Manivannan had tackled the question as to whether New Delhi had upheld the principle of R2P in letter and spirit in its Sri Lanka policy. A careful analysis of India’s policy towards Sri Lanka clearly brings out that on crucial occasions India had upheld this principle. Few illustrations are given below to substantiate this point.

The first organized riots against Tamils took place in Colombo in 1958 when lumpen sections of the Sinhalese populations went on an orgy of violence and murder. As a result, many Tamils were feeling unsafe in Colombo. Sensing the feeling of insecurity among the Tamils, YD Gundevia, then Indian High Commissioner, told Oliver Goonetileke, Governor General of Ceylon, that New Delhi was willing to provide ships so that the Tamils could move to the safety and security of Jaffna peninsula. New Delhi did not consider what was happening in Sri Lanka to be the domestic affair of Sri Lanka; on the contrary, India felt that it had a moral responsibility to come to the rescue of the Tamils. Ships were made available and hundreds of Tamils were taken from Colombo to Kankesenthurai. There were nearly 15000 Sinhalese living in Jaffna peninsula at that time, many of them employed in bakery business. There was no feeling of insecurity among them, but many of them decided to return to Sinhalese areas. They were brought back to Colombo.

The second incident when New Delhi upheld the principle of R2P took place in 1981 when riots were organized in the hill country by powerful forces within the Sinhalese community, including some important Ministers in the Jayewardene cabinet. The Sinhalese objective was to drive out as many hill country Tamils as possible to India before the Sirimavo-Shastri Pact ended in October 1981. The plantation areas, surrounded by Sinhalese villages, witnessed unprecedented violence. Thomas Abraham, then Indian High Commissioner in Sri Lanka, asked Ranjan Mathai, First Secretary, and Gopal Krishna Gandhi, First Secretary, to go to the hill country for an on the spot study of the situation. The two Indian diplomats, in their report to the High Commissioner, gave a graphic account of the violence unleashed by the Sinhalese thugs against innocent Indian Tamils. Thomas Abraham decided to go to the riot-affected areas to understand the gravity of the situation. He informed WT Jayasinghe, Foreign Secretary that he was proceeding to the hill country. Jayasinghe responded that Colombo will not be able to provide security. Thomas Abraham responded, “I did not ask for security. I am informing you about my plan because it is customary for a High Commissioner to inform the Foreign Secretary whenever he goes out of the capital”. Thomas Abraham met the affected people and understood their agony and suffering. Soon after his return to Colombo Thomas Abraham made an announcement that If Colombo will not restore law and order in the plantation areas India knows what to do. The curt message had telling effect; it sent shivers through the spines of Sinhalese leaders. President Jayewardene acted swiftly and law and order was immediately restored in the hill country.

The third example took place in May 1987 when Colombo embarked upon Operation Vadamarachi to militarily solve the ethnic problem. The Tamil militants were running away from the battle scene. Rajiv Gandhi and JN Dixit made it clear that India will not permit a military solution to the ethnic problem. New Delhi dispatched food and medicines through boats to Sri Lanka, but when these boats were prevented from entering Sri Lankan waters, the Indian Air Force planes entered Sri Lanka and dropped much needed food and medicines. Attempts made by President Jayewardene to get Pakistan and China involved on his country’s behalf did not succeed, both countries were unwilling to risk a war with India on behalf of Sri Lanka. Events moved swiftly culminating in the India-Sri Lanka Accord of July 1987.

New Delhi unfortunately was unwilling to take any steps to rescue the civilian population during the Fourth Eelam War when the Sri Lankan Air Force planes resorted to savage bombing of Tamil civilian population. Many in India, including this reviewer, requested that New Delhi, in concert with the United States and members of the European Union, should get involved in Sri Lanka to rescue the innocent Tamil civilians, who were trapped between the Sinhalese Lions and the Tamil Tigers. The fact of the matter was that New Delhi knew what was happening in Sri Lanka on an hour-to-hour basis; it was as keen as the Sri Lankan Government to destroy the Tigers, if in that process innocent Tamils got killed, the collateral damage could not be prevented.

I would like to make another point. The value of the book would have been further enhanced if Prof. Ramu Manivannan had devoted sufficient space to describe how the Tigers degenerated into one of the most ruthless terrorist organizations in the world and how, in that process, Prabhakaran lost the sympathy and support of the international community. In the early phase of the ethnic conflict many justified the violence of the Tamil militants as a response against brutal state oppression and as “emancipator violence” on behalf of the Tamil people. However the violent actions of the Tigers against innocent civilians starting with the massacre of the Buddhist pilgrims in Anuradhapura, the murder of political opponents and the forcible conscription of Tamil children into the “baby brigade” alienated large sections of the people. As far as India is concerned, the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi by the suicide squad of the Tigers turned Indian opinion against the Tigers. The terrorist actions of the Tigers not only led to the brutalization of Sri Lankan Tamil society, it also led to the shrinkage of the democratic space in Sri Lanka. As Neelan Thiruchelvam, himself an innocent victim of the Tigers, has written: “The violence of the victim soon consumed the victim and they also became possessed by the demons of racial bigotry and intolerance which had characterized the oppressor. These are seen in the fratricidal violence between Tamils and Muslims, in the massacres at Kathankudy mosque, in Welikanda and Medirigiya, and in the forcible expulsion of the Muslims from the Mannar and Jaffna districts”. I know that Ramu and Ashik Bonofer are conscious of these crimes of the LTTE; perhaps since the focus of the book is on the last stages of the Fourth Eelam War, these incidents do not find a mention in the book. However, reference to the crimes of the Tigers would have resulted in the balanced representation of the facts.

I would like to conclude the review with the famous lines of Pablo Neruda: “Perhaps this war will pass like others which divided us; leaving us dead, killing us along with the killers; but the shame of this time puts its burning fingers in our faces; who will erase the ruthlessness hidden in innocent blood?”.

(Dr, V, Suryanarayan is former Senior Professor, Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Madras)

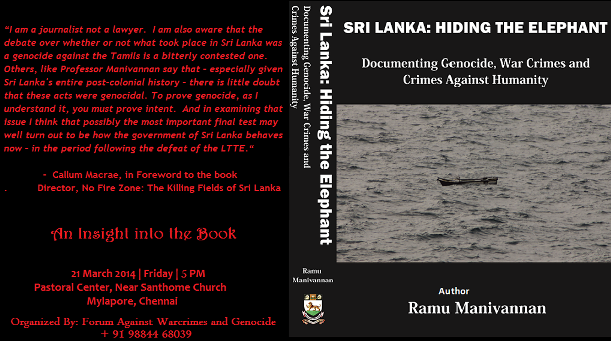

Ramu Manivannan, Ed., Sri Lanka – Hiding the Elephant: Documenting Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity (Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Madras, Chepauk, Chennai – 600 005), pp. 976, Price Rs. 2000/-

Orders for the book may be placed with the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Madras, Chepauk, Chennai – 600 005.