Campaigning journalist, film-maker, author and fervent critic of US and British foreign policy

Obituary by Anthony Hayward/ The Guardian

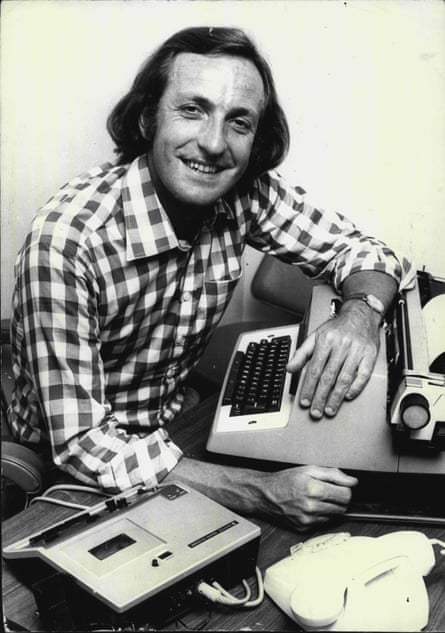

John Pilger, who has died of pulmonary fibrosis aged 84, was a journalist who never shirked from saying the unsayable. Across half a century, in newspapers and in his documentary films – many for ITV, but later also in the cinema – he became an ever stronger voice for those without a voice, and a thorn in the side of those in authority.

He was a fervent critic of US and British foreign policy. In 2006, on a panel at Columbia University, New York, to discuss Breaking the Silence: War, Lies and Empire, Pilger asserted that “journalists in the so-called mainstream bear much of the responsibility” for the devastation and lives lost in Iraq, by not challenging and exposing “the lies of Bush and Blair”.

The impact of Pilger’s journalism was enormous. In 1979, he entered Cambodia after the Vietnamese had thrown out Pol Pot and the murderous Khmer Rouge. In a report that took up much of the first half of the Daily Mirror, he revealed that possibly more than two million people, from a population of seven million, had died as a result of genocide or starvation, while another two million faced death from food shortages or disease.

Haunting images of emaciated children, and doctors battling to save lives, were subsequently seen in Pilger’s documentary Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia, which was watched in 50 countries by 150 million viewers, and won more than 30 international awards.

Displaying his talent for putting a human tragedy into a political context, he laid part of the blame on the US, which had secretly and illegally bombed Cambodia, creating the turmoil that allowed Pol Pot to seize power. Also, said Pilger, western governments were unwilling to give substantial aid to those now running Cambodia for fear of displeasing the US, which had been defeated in the Vietnam war only four years earlier.

Pilger’s reporting helped to raise $45m in relief and earned him a second journalist of the year title in the British Press Awards (the previous one was for his dispatches from Vietnam) and the United Nations media peace prize. Over the next decade, he continued to return to Cambodia and report on the power politics. He himself survived an ambush after being put on a Khmer Rouge death list.

From his first ITV documentary, in 1970, Pilger made waves. In The Quiet Mutiny, for Granada Television’s World in Action current affairs series, he broke the story of the disintegration of morale among US troops in the Vietnam war – and reported that some officers were being killed by their own soldiers.

Following a complaint by the US ambassador in London, the ITA – then commercial television’s regulator – rapped Granada over the knuckles, setting the tone for future battles with Pilger over questions of balance and impartiality.

His ITV series Pilger (1974-77), made by ATV, looked into many controversial subjects in Britain, Pilger’s adopted country after he left his native Australia in 1962. He reported on 98 uncompensated thalidomide victims, NHS cuts, racism, poverty and the treatment of children with learning disabilities. Abroad, he went undercover to interview Czech dissidents.

Throughout this time, the ITA’s successor, the IBA, insisted that his films should be introduced on screen as a “personal view” rather than objective reporting. Pilger described David Glencross, the regulator’s chief programme officer, as “commercial television’s chief censor” and regarded the IBA’s calls for objectivity, balance and impartiality as “code for the establishment view of the world, against which most perspectives are measured”.

Pilger said he looked at politics from the ground up, and he enjoyed the support of Richard Creasey, who became ATV’s head of documentaries and negotiated with Glencross the right to screen films without the “personal view” label. Nevertheless, when ATV became Central Independent Television and Pilger tackled the language used to promote nuclear weapons in his 1983 documentary The Truth Game, the IBA insisted that a “balancing” programme be made by someone else (it turned out to be Max Hastings) before it could be screened.

Pilger was one of the first journalists to return to Vietnam after the war, and among his other films of the period were Do You Remember Vietnam (1978), and Heroes (1981), for which he took five disabled American war veterans back to former combat zones to reflect on what he described as a war fought “in the cause of nothing”.

However, his claims in Cambodia: The Betrayal (1990) about the SAS training Khmer Rouge guerrillas in the 1980s led Pilger and Central to lose a libel action.

Many of his documentaries exposed human rights abuses. At great personal risk, Pilger and his regular director, David Munro, entered countries run by military dictatorships. In Death of a Nation: The Timor Conspiracy (1994), he interviewed eyewitnesses to genocide by the occupying Indonesian regime in East Timor and revealed an unreported massacre. In Inside Burma: Land of Fear (1998), he uncovered the generals’ torture.

He explored UN sanctions on Iraq in the decade before the US-led invasion in Paying the Price: Killing the Children of Iraq (2000), globalisation in The New Rulers of the World (2001) and the Middle East in Palestine Is Still the Issue (2002).

When Pilger made Breaking the Silence: Truth and Lies in the War on Terror (2003), he unravelled the background to 9/11 and the invasion of Afghanistan, highlighting “hypocrisy” by the US and British governments. He opened with the words: “This film is about the rise and rise of rapacious imperial power and a terrorism that never speaks its name because it is our terrorism.”

Similar themes emerged in The War on Democracy (2007), about US interference in Latin American countries, and The War You Don’t See (2010), a chronicle of reporting from the frontline made with the director Alan Lowery, another regular collaborator. “Why do many journalists beat the drums of war regardless of the lies of governments?” Pilger asked.

Later, his focus was on a country deemed by the US to be a threat to its global power in The Coming War on China (2016) and starved resources and creeping privatisation in The Dirty War on the National Health Service (2019).

Among more than 60 documentaries, Pilger also made Stealing a Nation (2004), on the British government expelling the population of the Chagos Islands, in the Indian Ocean, in the 60s so that the US could set up a military base there.

But a constant subject of Pilger’s films over almost 40 years, beginning in 1976, was his homeland and the treatment of Indigenous Australians. Most significantly, he made The Secret Country: The First Australians Fight Back (1985), the bicentenary trilogy The Last Dream (1988) and Utopia (2013), telling the story of his great-grandparents’ arrival in Australia as convicts, Aboriginal poverty and deaths in police custody, and the stolen generations of mixed-heritage children taken from their families.

Pilger was born in Sydney, to Elsie (nee Marheine), a teacher, and Claude Pilger, a carpenter. He attended Sydney Boys’ high school and won medals as a swimmer. In 1958 he joined Australian Consolidated Press, working on the Sydney Sun, and then the Daily and Sunday Telegraph.

He freelanced in Italy before moving to Britain in 1962 and becoming a subeditor with the Reuters news agency. A year later, he joined the Daily Mirror as a subeditor, then a reporter noted for his investigative journalism, descriptive writing and tireless campaigns.

Roaming the world, he was banned from South Africa by the apartheid regime in 1967 and was standing metres away when Robert F Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles the following year. He left the Mirror in 1985 and wrote for other papers, including the Guardian. He was a supporter of the WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange.

The ferocity of rightwing criticism of his views indicated the effectiveness of his journalism.

Among dozens of honours, Pilger received an Emmy for Cambodia: The Betrayal, and, in 1991, Bafta’s Richard Dimbleby award.

His 1971 marriage to the journalist Scarth Flett ended in divorce. He is survived by his partner of more than 30 years, Jane Hill, a magazine journalist, a son, Sam, from his marriage, and a daughter, Zoe, from a relationship with the journalist Yvonne Roberts.