The administration of President Mahinda Rajapaksa won the ethnic war, but Sri Lanka’s protracted conflict is more alive than ever. There is a lot of talk about how the situation in the North and East has improved, but most of these assertions are misleading. The rebuilding of physical infrastructure alone is not a very helpful indicator when it comes to reconciliation.

The dearth of psychosocial assistance being provided, the thousands of disappeared who remain missing and the continued erosion of the rule of law contradict the Government of Sri Lanka’s (GoSL) assertion that the country has made meaningful progress on the reconciliation front.

At this point, national reconciliation is not just illusory; it is a fantasy and will be as long as the present regime maintains its antipathetic stance towards human rights, devolution and the implementation of the LLRC recommendations.

As the 22nd session of the UN’s Human Rights Council (HRC) comes to the attention of both domestic and international observers, it’s important to keep a few things in mind.

First, the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) has – in every sense of the word – ignored the HRC resolution and has clearly shown that it is not committed to implementing the recommendations prescribed in its own presidentially appointed commission. Thoughts about accountability and/or a thoughtful examination of the serious violations of humanitarian law and the Geneva Conventions are taken even less seriously. That is the government’s record and there’s no getting around it. Inaction, prevarication, delay, dissimulation and the institutionalization of impunity are to be expected from this administration.

It’s been nearly four years since the end of Sri Lanka’s devastating civil war and the present administration in Colombo is feeling the heat for its deplorable human rights record. Nevertheless, one has to wonder why the international community has let Sri Lanka’s human rights disaster slip through the cracks for far too long. This

needs to change.

Now, other crises may be more pressing and this aspect of advocacy and diplomacy shouldn’t be overlooked. But Sri Lanka remains important – not least because the international community cannot and should not condone the “Sri Lanka model.” Doing so would encourage other authoritarian regimes to tolerate massive civilian casualties during wartime. The way the GoSL ended the war in 2009 isn’t something to emulate; it’s a piece of history that should stay as history and never recur in any part of the world. And, let us not forget there are over 200,000 people who witnessed the slaughter and are still looking for answers from the international community – as to why they stood by and watched it happen.

Some have been wondering if the notion/law of “Crimes against Humanity” is little more than ink on paper. Or, perhaps more disturbingly: Were they not considered to be part of Humanity? Did the catastrophic events that unfolded in early 2009 not merit a stronger, more meaningful international response?

Events in Colombo

This past Thursday in Colombo, the GoSL briefed diplomats on the upcoming HRC session and the government’s implementation of the LLRC recommendations. In making his final remarks, Minister of External Affairs G.L. Peiris encouraged diplomats to look at the complex challenges Sri Lanka is currently facing. He went on to emphasize that the GoSL had already undertaken “colossal” infrastructure programs in the Northern Province.

While the situation on the island is undoubtedly complex, Mr. Peiris is missing the larger point: GoSL’s response towards reconciliation, human rights and a political solution has been misguided, feckless and underwhelming. As a result, it is imperative that GoSL begin to implement many of the LLRC recommendations in the short-term.

Before the end of this month, The Social Architects (TSA) will be releasing its third major report, an examination of the GoSL’s implementation of the LLRC recommendations. The report will provide both quantitative and qualitative analysis related to the GoSL’s LLRC action and inaction. The publication of this report will shed light on what’s really happening in Sri Lanka, especially the North, East and Hill Country. TSA’s research has been supported by extensive field research throughout the country’s conflict-affected areas.

But for now, TSA will leave readers with a few notable statistics from data gathered from its first 1,200 survey participants.

The Methodology

The questionnaire for this survey was developed around 34 LLRC recommendations – selected for their urgency and relevance for bringing about genuine reconciliation.[1]

This consultative process ensured that the selected recommendations and the questionnaire itself reflect the most pressing issues standing in the way of reconciliation, human rights and a lasting peace. The questions for the survey’s eleven sections were developed based on the feedback from discussions with community members.

Sample Size and Characteristics

TSA conducted the survey from a sample of 2,000 households through 244 villages/communities in nine districts: Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mullaitivu, Mannar, Vavuniya, Trincomalee, Batticaloa, Ampara and Nuwara Eliya.

High levels of military surveillance and the presence of informants at the community level (particularly in the North) would have made random sampling a risky and potentially dangerous undertaking, as much for the respondents as the interviewers. Given the circumstances, snowball sampling was therefore considered the most suitable methodology to conduct the survey in the safest possible conditions.

Snowball sampling relies on existing social networks within a given population, using a small group of initial respondents tasked with nominating other participants meeting the criteria.

The survey was conducted in communities where TSA already had a presence – including an extensive network of trustworthy grassroots contacts.

TSA acknowledges the potential for community bias resulting from using this methodology. In order to minimize the likelihood of bias, TSA randomly selected two members from these existing grassroots networks comprised of 15 to 20 individuals, as initial respondents. Those two respondents each identified five individuals within their social network, six of whom were randomly selected as respondents by TSA and asked to identify a further five individuals each (for a total of 30). Amongst this last group of 30 people, TSA randomly selected 18 individuals as final respondents, bringing the total for each community to 26 participants.

Data Collection

Data collection was conducted over a period of 20 days by external data collectors (essentially university students and members of community-based organizations). All data collectors received training on data collection techniques and interview methods prior to starting the survey, which was first piloted in two villages (one in the East, one in the Hill country). Data collectors were explicitly instructed not to give advice on solving issues discussed to fill out the questionnaire and were guided on conducting interviews in a neutral manner. Feedback received from data collectors on the questionnaire during the pilot phase was incorporated into the final questionnaire.[2] In each district, one TSA supervisor observed the data collection process in all communities to ensure it was conducted in an independent and neutral fashion.

Findings

Disappearances

Sri Lanka has long had a problem with disappearances. Accordingly, the LLRC sought to address this issue in its final report, which includes the following two recommendations:

Recommendation 9.46: Investigate allegations of abductions, enforced or involuntary disappearance; bring perpetrators to justice.

Recommendation 9.51: “…the Commission recommends that a Special Commissioner of Investigation be appointed to investigate alleged disappearances and provide material to the Attorney General to initiate criminal proceedings where appropriate.”

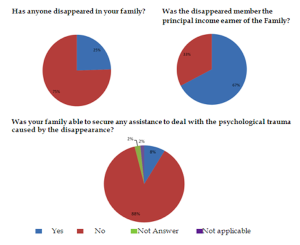

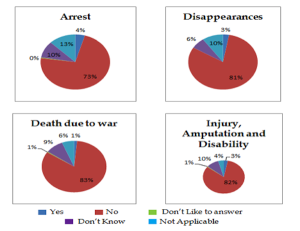

Yet the GoSL’s record on disappearances continues to be a concern. Appallingly, 25% of TSA survey respondents have had a family member disappear. And that individual was usually the principal incomer earner of the family.

Recommendation 9.58: “The families need to be assisted to deal with the trauma of not knowing the whereabouts of their family members […]. They could also be assisted financially in situations where the missing persons had been breadwinners. Legal aid should be provided where necessary.”

The provision of psychosocial services, something that falls almost exclusively under the purview of the GoSL, is another major issue cited in the LLRC’s Final Report that the GoSL still hasn’t addressed. In fact, based on TSA’s preliminary findings, it appears the GoSL is nowhere near close to fully implementing this recommendation, as 90% of respondents in need of psychosocial assistance have been unable to obtain it.

Language Rights

The subject of language rights featured prominently in the LLRC Final Report, which includes the following two recommendations:

Recommendation 9.41: “The official bodies for executing language policies and monitoring performance should have adequate representation of Tamil speaking people and Tamil speaking regions. The full implementation of the language policy should include action plans broken down to the community level […]”.

And:

Recommendation 9.47: “It should be made compulsory that all Government offices have Tamil-speaking officers at all times. In the case of Police Stations they should have bi-lingual officers on a 24-hour basis. A complainant should have to the right to have his/her statement taken down in the language of their choice.”

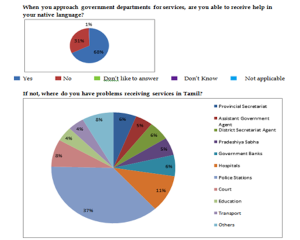

Yet, here again the GoSL’s performance has been, to say the least, substandard. The graph below clearly indicates that service delivery in the Tamil language is still grossly inadequate. Despite the recommendation above to have Tamil-speaking officers 24/7, police stations rank far above any other service providers in terms of their lack of Tamil speaking personnel.

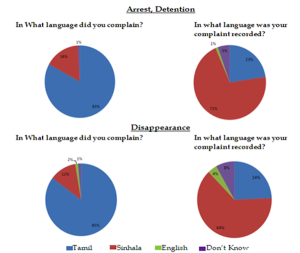

The situation in police stations and places that are to provide redress is further reflected in the graphs below, illustrating the difficulties experienced by victims of arrests, detention and disappearances to file a complaint in their own language:

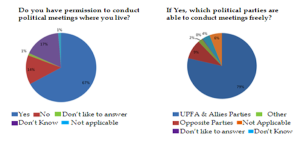

Freedom of Association

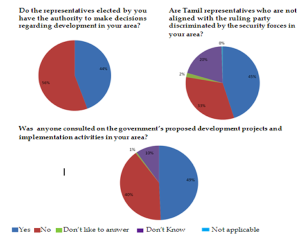

Based on TSA’s findings, it is clear that not all political parties are treated equally by the state security apparatus. Political parties which form part of the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) are able to meet freely throughout the North, East and Hill Country; whereas opposition parties like the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) and others have had their freedom of association curtailed.

Many community members are very frustrated with the lack of progress regarding Government – TNA talks, so this closing of political space in the country’s conflict-affected areas is a discouraging sign. What’s now needed is a wider opening for genuine political dialogue and debate.

Inclusive Development

The regime in Colombo has sought to allay international concerns by purportedly advocating for an inclusive approach to development which would inherently bring lasting peace and meaningful reconcilation. The GoSL’s Plan of Action to implement the LLRC recommendation and its National Action Plan for the Protecton and Promotion of Human Rights both cite the importance of community participation. As per the LLRC Final Report:

Recommendation 9.223 “The Government should ensure that development activities should be carried out in consultation and with the participation of the local people.”

And:

Recommendation 9.227 “It is important that the Northern Province reverts to civilian administration in matter relating to the day-to-day life of the people…The military must progressively recede to the background[…]”.

TSA’s Shadow Action Plan went even further and embraced community participation at every stage of the process, but the GoSL has taken a more lethargic approach toward the question of community participation.

Furthermore, the results from the following survey question are both discouraging and illustrative:

Were you informed of any baseline study undertaken by the government officials to assess the improvement in livelihood opportunities? [3]

Other Preliminary Findings[4]

- 53% of arrested individuals were not taken before a Magistrate prior to being issued a detention order.

- As noted, 25% of respondents have had a relative disappear.

- And 47% of respondents had a relative disappear between September 2008 and May 2009. Moreover, the security forces are perceived to be responsible for 75% of disappearances.

- Military interference in civilian affairs still is still quite high, as 47% of respondents felt elected representatives lack the authority to make decisions on development activities.

- The military is perceived as the main interfering actor for 37% of respondents.

- 43% of respondents indicated the military is involved in civil/community activities in their area.

- 27% of respondents indicated that communal spaces and buildings were used by military.

- 80% of respondents indicated military encampments are situated close to their residence, within 5 kilometers.

Final Thoughts

The GoSL remains largely uninterested in addressing the root causes of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict. For that to change, a concerted effort must be made by the present administration in Colombo.

Again, critics of this regime have every right to be concerned that upcoming events in Geneva might be disappointing. But let there be no mistake: by the conclusion of the HRC’s 22nd session everybody – from Beijing to Bangkok to Washington – will know what’s really happening on this island. When meaningful change will happen – nobody knows exactly – but nobody has a monopoly on the truth.

– GV