The president could have made the case for deeper reform.

The Diplomat/By Taylor Dibbert

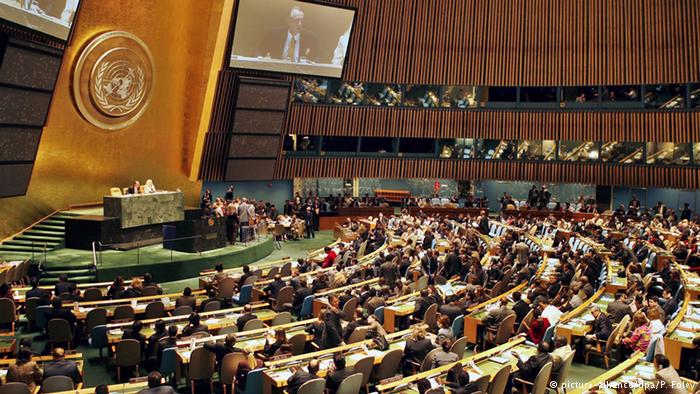

Sri Lanka’s Maithripala Sirisena spoke at the United Nations (UN) on Wednesday. Mr. Sirisena touched on economic development, poverty, drugs and more. It was a brief speech. However, Mr. Sirisena could have at least attempted to make a clear, articulate case for the most important aspects of the coalition government’s reform agenda, especially transitional justice. Regrettably, the president failed to do that.

For example, here’s an area that deserved more attention:

In the domestic front, my government has taken effective measures to strengthen democracy, rule of law and good governance in the country paving the way for a positive change to ensure that there will be no more wars on the soils of my country, Sri Lanka. The reconciliation process that is underway today has learnt from the bitter experience of a brutal war of three decades. It will guarantee that my country will not see the cruelty of war and terrorism again and that all communities will live peacefully in a rational and a free-thinking Sri Lanka. For this noble purpose, Sri Lanka welcomes the collaboration and the blessings of the world.

This was a fairly weak performance from the president – particularly when one recognizes that Colombo continues to drag its feet on a host of war-related issues: the detention of Tamil political prisoners, the military’s continued occupation of civilian land, pervasive militarization across the country’s north and east, among other matters. Leaving the government’s sincerity toward deeper reform aside for a moment, one could argue that the environment to implement a credible, comprehensive transitional justice package does not yet exist, especially in the northern and eastern provinces.

In other international settings, Mangala Samaraweera – the country’s foreign minister – has issued soaring, exuberant speeches that don’t reflect reality, although at least Mr. Samaraweera has attempted to talk about some of the more controversial components of the government’s reform agenda. To a large degree, the foreign minister’s remarks have been intended to express what Colombo thinks the international community wants to hear. But then, usually, similar messages are neither conveyed to a domestic audience nor backed up with concrete action.

Frankly, Mr. Sirisena’s UN speech serves as yet another reminder that, even at the highest levels of government, Colombo remains afraid of making a persuasive case for transitional justice or healing the wounds of war. Unless Mr. Sirisena and others start talking more consistently about the requisite reforms (especially within Sri Lanka), it’s hard to imagine that the government would ever get around to properly implementing them.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry met with Mr. Sirisena on Wednesday as well. Mr. Kerry reminded us that the United States is “very encouraged by the steps that the president is taking and Sri Lanka is taking with respect to reconciliation, and they’re also making important economic reforms.”

Here again, another U.S. official speaks about “reconciliation” in Sri Lanka, but “accountability” (for wartime abuses) is not mentioned. That said, the secretary’s brief remarks could have been worse. In April, Samantha Power referred to Sri Lanka as “a global champion of human rights and democratic accountability.” Power’s remarks were way off base, although a range of senior US officials have been excessively congratulatory too. “So the story of Sri Lanka is a great one and we’re really happy to be able to meet,” said Mr. Kerry on Wednesday.

A “great” story, really? If you’re looking for an accurate depiction of the current state of affairs in Sri Lanka, be sure to steer clear of Washington’s rhetoric.

The Diplomat