Secret files reveal Rajapaksa ruling family member and husband used secret companies to stash riches around the world.

In early 2018, workers in a London warehouse carefully loaded an oil painting of Lakshmi, the Hindu deity of wealth, onto a van bound for Switzerland.

The painting, by 19th-century Indian master Raja Ravi Varma, depicts the four-armed goddess clad in a red sari with gold ornaments and standing atop a lotus flower. It was one of 31 works of art, altogether worth nearly $1 million, that were being shipped to the Geneva Freeport in Switzerland. That vast, ultra-secure warehouse complex, larger than 20 soccer fields, stores among its many treasures what the BBC once called “the greatest art collection no one can see.”

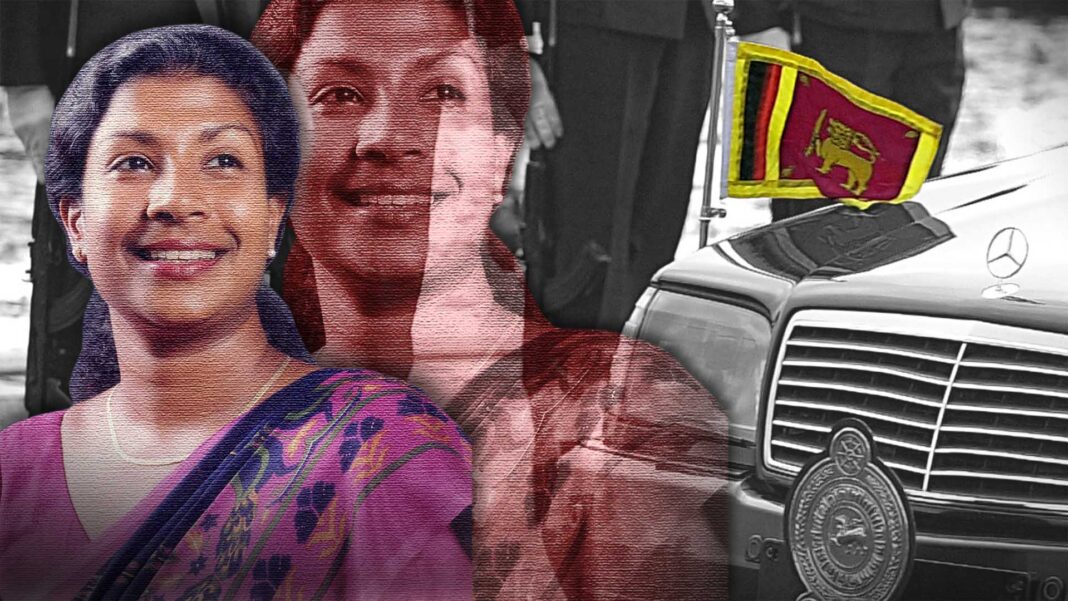

His wife, Nirupama Rajapaksa, is a former member of Sri Lanka’s Parliament and a scion of the powerful Rajapaksa clan, which has dominated the Indian Ocean island nation’s politics for decades.

The owner of “Goddess Lakshmi,” and the artworks in transit with it, as recorded on the packing slip, was a Samoan-registered shell company with an unremarkable name, Pacific Commodities Ltd. But a cache of leaked documents from Asiaciti Trust, a Singapore-based financial services provider, indicates that a politically connected Sri Lankan, Thirukumar Nadesan, secretly controls the company and thus is the true owner of the 31 pieces of art.

His wife, Nirupama Rajapaksa, is a former member of Sri Lanka’s Parliament and a scion of the powerful Rajapaksa clan, which has dominated the Indian Ocean island nation’s politics for decades.

The confidential documents, obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, show that as the country was ravaged by a bloody, decades-long civil war, the couple set up anonymous offshore trusts and shell companies to acquire artwork and luxury apartments and to store cash, securities and other assets in secret. They were able to amass and hide their fortune in secrecy jurisdictions with the assistance of financial services providers, lawyers and other white-collar professionals who asked few questions about the source of their wealth – even after Nadesan became a target of a well-publicized corruption investigation by Sri Lankan authorities.

As of 2017, Rajapaksa and Nadesan’s offshore holdings, which haven’t previously been made public, had a value of about $18 million, according to an ICIJ analysis of a Nadesan trust’s financial statements. The median annual income in Sri Lanka is less than $4,000.

In emails to Asiaciti, a longtime adviser of Nadesan’s put his overall wealth in 2011 at more than $160 million. ICIJ couldn’t independently verify the figure.

The records describing the financial machinations of Nadesan and Nirupama Rajapaksa are among more than 11.9 million records from Asiaciti and 13 other offshore service providers obtained by ICIJ and shared with global media partners as part of the Pandora Papers investigation. The two-year investigation found billions pouring out of impoverished and autocratic nations and into private accounts listed under the names of shell companies and trusts, often hidden from courts, creditors and law enforcement.

Among the results: Governments around the world are starved of desperately needed resources, and global wealth is concentrated into ever fewer hands. In Sri Lanka, where economists say the income gap between the poor and the rich continues to increase, lax tax regulations have been a boon for the wealthy and powerful. The rest of the country which is still recovering from the civil war, has been left with little to invest in schools, health care and other social programs.

Piyadasa Edirisuriya, a former Sri Lankan finance ministry official and now a lecturer at Australia’s Monash University, says that offshore financial services firms could stop illicit money flows by conducting due diligence on clients and monitoring their transactions. “But in international financial centers, many don’t do that,” he said. “That is why people in countries like Sri Lanka can earn money in corrupt ways and easily use these tax havens to send them overseas.”

Sri Lanka’s president is Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Nirupama Rajapaksa’s late father was his cousin. The president’s older brother, Mahinda Rajapaksa, is prime minister. Human rights groups have accused the brothers of war crimes. Former government officials have alleged that the family has amassed a multibillion-dollar fortune and hidden part of it in bank accounts in Dubai, Seychelles and St. Martin. At least eight family members and loyalists have been investigated by authorities and some have been charged with crimes including fraud, corruption and embezzlement, according to media reports.

Nirupama Rajapaksa’s husband, Nadesan, faces allegations that he secretly helped one of his in-laws, a government minister, build a posh villa with government funds.

In a 2015 affidavit, Gotabaya Rajapaksa claimed that he and some members of his family had been the targets of a “vindictive and vicious campaign.”

In response to questions from ICIJ, Nirupama Rajapaksa and Nadesan said that their “private matters are dealt with by [the couple] properly with their advisers” and did not comment on their companies and trusts.

Nadesan added that the 2016 charges against him are “spurious and politically motivated.”

Asiaciti said that the firm is “committed to the highest business standards, including ensuring that our operations fully comply with all laws and regulations.”

It did not comment on the services it provided to Nadesan and Nirupama Rajapaksa.

A dynasty rises amid civil war

Civil war ravaged Sri Lanka for a quarter-century. The seeds of the conflict go back to 1948, when nationalists, led by Don Alwin Rajapaksa, granted certain citizenship privileges to the Sinhalese majority, alienating the country’s ethnic Tamil minority. Animosity boiled over into open conflict in 1983, when the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, an insurgent group, killed 13 government soldiers.

The years that followed were marred by torture, abductions, arbitrary arrests and the massacre of civilians, by the separatists and by government forces. One of the army chiefs leading the fight against the Tigers was Gotabaya Rajapaksa – Don Alwin’s son. Gotabaya was nicknamed “The Terminator” because of his reputation for ruthlessness.

The leaked records show that as the conflict intensified, Nirupama Rajapaksa, now 59 years old, and her husband, Nadesan, were establishing shell companies and trusts in offshore jurisdictions. The reasons, according to a client review in the leaked files: “confidentiality and estate planning.” Other powerful elites in the region, including relatives of Indonesian and Filipino autocrats Suharto and Ferdinand Marcos, have followed the same playbook.

In 1990, Nadesan, a British-educated businessman and trustee of several Sri Lankan Hindu charities and temples, set up a trust and a shell company in the Channel Islands, British crown dependencies off the coast of France.

The company, Pacific Commodities Ltd., would collect millions of dollars, an internal document shows, advising foreign companies doing business with the Sri Lankan government. One client was Contrac GmbH, a German manufacturer that supplied airfield buses for a project involving the country’s national airline company, now SriLankan Airlines.

Contrac said the company was not able to comment on the project. The case is “31 years old and therewith far too old for our physical and data archive,” a spokesperson said..

As the civil war escalated in May 1991, Rajapaksa and Nadesan set up Rosetti Ltd., another shell company, on the Channel Island of Jersey. It would provide consulting services “mainly in relation to inward investment into Sri Lanka,” according to confidential documents.

The couple used Rosetti to buy a luxury apartment in Sydney, near Darling Harbour. They used the same shell company to buy three apartments in London, one by the Thames River that they resold a few years later for $850,000, and two worth more than $4 million that were rented out “on a commercial basis.”

The properties have not been previously linked to the couple. Buying them through the Channel Islands company virtually ensured as much. The jurisdiction allows companies incorporated there to shield their true owners from public view while paying relatively little if any taxes.

As the offshore fortune continued to grow, Nirupama Rajapaksa entered politics. In 1994, she was elected to the Sri Lankan Parliament.

Power couple

In 2009, the Sri Lankan army killed Tamil chief Velupillai Prabhakaran, effectively ending the quarter century-long civil war.

Mahinda Rajapaksa – Gotabaya’s brother – was hailed as the leader who had defeated the rebels. Despite war crime allegations by European Union officials and other foreign observers,he won a second term in the 2010 presidential election.

Rajapaksa assigned himself the defense, finance, ports, aviation and highways portfolios and retained Gotabaya as secretary of the Ministry of Defence and Urban Development. He named another brother, Basil, minister of economic development and yet another, Chamal, became speaker of Parliament.

Nirupama Rajapaksa got a government post, too: deputy minister of water supply and drainage.

Altogether, the Rajapaksa family controlled up to 70% of the national budget, the Al Jazeera news channel reported.

In the world of international finance, government officials like Nirupama Rajapaksa and their families are considered “politically exposed persons,” or PEPs, and are supposed to be subjected to extra scrutiny – in case, for example, they are exploiting their positions for financial gain. Financial services providers are required to alert authorities if they suspect clients are involved in illegal activity.

Asiaciti began to include Nadesan in a special register for PEP clients. After 2010, Nirupama Rajapaksa’s proper name rarely appeared in the leaked documents related to her family’s offshore holdings, and she was sometimes mentioned only as “wife of the settlor,” the files shottps://www.documentcloud.org/documents/21072241-asiaciti-review_-nadesan-trustw.

Asiaciti officers said they screened some of Nadesan’s transactions for suspicious activity and checked media reports for allegations of criminal behavior, documents show. The files indicate that the oversight was flawed. An internal inspection report suggests that the Asiaciti officer in charge of anti-money- laundering reviews didn’t provide detailed information on Nadesan’s background — which could have raised concerns about the wealth flowing out of Sri Lanka and into his offshore accounts. And Asiaciti employees were “unable to locate” periodic records on assessments of the client’s activities.

Asiaciti told ICIJ that the firm maintains a “strong” compliance program. “However, no compliance program is infallible,” it said in an emailed response.

“When an issue is identified, we take necessary steps with regard to the client engagement and make the appropriate notifications to regulatory agencies,” the firm said.

After his wife assumed her government post, Nadesan began to transfer assets to new secrecy jurisdictions. Asiaciti set up a trust for him in New Zealand in 2012 and later moved it to the Cook Islands in the South Pacific, a jurisdiction that U.S. law enforcement agencies consider “vulnerable” to money laundering, with laws that protect trust beneficiaries from court judgments.

Asiaciti also transferred Pacific Commodities from the Channel Islands to Samoa, another South Pacific island nation, which is on the European Union’s blacklist of noncooperative countries because of its “harmful preferential tax regime.”

By this point, Nadesan’s consulting company had become the owner of an art collection, which included paintings by noted Sri Lankan cubist George Keyt and by Indian artists Jamini Roy (known for combining Indian and Western styles) and Maqbool Fida Husain (known as the “Picasso of India).”

By 2014, the collection would grow to include 51 pieces with an estimated total value of more than $4 million. Some of the art was stashed in a London warehouse; other works were stored in the Geneva Freeport.

John Zarobell, San Francisco University associate professor and an expert on the economics of art, said art is seen by some collectors as just another commodity, like real estate or gold. “It’s one of those assets that you can use to diversify [your portfolio] and pass that value to others,” he said.

The couple’s rental properties were yielding thousands of dollars in income, sometimes paid in cash. In London, agents working for Nadesan would vet prospective residential tenants. In Sydney, a contractor would check that the TV, window blinds and other accessories in the couple’s luxury apartment were working properly.

Amid the flurry of offshore activity, Nadesan bought a 16-acre plot near Colombo, which would later come under scrutiny by investigators.

In Colombo, Nadesan became chairman of a state company that owned the local Hilton hotel. He presided over galas attended by members of high society.

In 2014, as the Sri Lankan government considered legislation to allow dual citizenship, Nadesan applied for a Cyprus passport after depositing $1.3 million in a bank there, according to the confidential files.

“Citizenship-for-sale” programs like Cyprus’ have been exploited by corrupt politicians and criminals to travel visa-free in the European Union and transfer money into EU countries without much scrutiny. The files don’t say if his application was successful.

As a government minister, Nirupama promoted local industry, shaking hands with Asian prime ministers and giving interviews. In one, she expounded on the difficulties faced by female politicians in a male-dominated environment.

“As women, we have better qualities than men and are more honest and are less vulnerable to bribes and corruption,” she said in a 2014 interview with a local magazine. “If we had more women running the country, it will be good.”

Reversal of fortune

In 2015, the Rajapaksa family’s fortunes shifted dramatically. Dogged by accusations of corruption and authoritarianism, Mahinda Rajapaksa lost the presidential election to a former ally who campaigned on a promise to reform. Soon after, a spokesman for the incoming cabinet told reporters that people close to the Rajapaksa government had secretly transferred $10 billion to Dubai, a notorious tax haven. “More than our country’s foreign reserves,” the spokesman added.

Mahinda Rajapaksa denied any wrongdoing. Several other Rajapaksa family members would also face corruption investigations.

Nirupama lost her deputy minister job.

A year later, she and her husband were implicated in a $1.7 million embezzlement case involving the 16-acre plot that Nadesan had acquired six years earlier.

In March 2016, financial authorities summoned the couple to give statements about the plot, upon which a villa had since been built.

Prosecutors suspected that the villa actually belonged to Basil Rajapaksa, the former economic development minister, and were trying to determine whether he had used public funds to build the villa with Nadesan’s help.

In a court deposition reported by local media, the villa’s architect testified that Basil Rajapaksa’s wife had attended a groundbreaking ceremony presided over by the presidential astrologer, and that the minister’s office had approved the construction plan, which included a gym, a swimming pool and a surrounding farm.

Leaked files show that, as the investigation continued in the summer of 2016, Nadesan began preparations to open a Dubai bank account for his investment company, which owned a Dubai-registered asphalt firm.

In confidential emails to a bank officer, he introduced himself as the husband of a politician in “semi-retirement” and owner of a 60-room hotel on the eastern coast of Sri Lanka. He signed the emails “TN.”

When the bank employee requested all statements from company bank accounts in the United Arab Emirates, as well as other business records, to comply with the bank’s due diligence policy, Nadesan was alarmed. He emailed Asiaciti officers instructing them to limit the amount of information they disclosed: “WE CANNOT [yield to] EVERY WHIM @ FANCY A BANK REQUIRES WITHOUT GIVING ANY COMMITMENT THAT WE WILL BE ON BOARDED,” he wrote in all caps. “THESE ARE CONFIDENTIAL SENSITIVE INFORMATION[.] WE HAVE TO DRAW A LINE AT A POINT”

“Kindly note [that the company] is NOT going to exhibit all bank accounts it holds in the UAE . . . under any circumstances, even if an account is not going to be opened,” Nadesan told the bank in a separate email.

In October, Nadesan was arrested on embezzlement charges related to the land and the villa east of Colombo.

Just before his arrest, he wrote a personal letter found in the leaked files to the new Sri Lankan prime minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, proclaiming his innocence. Nadesan said he wasn’t aware until he read news reports that Basil Rajapaksa had built a house on his property. Then he sold the land, he said, to avoid “harm to [his] name and reputation.”

“I request your good self to appreciate that I have not done anything improper or illegal and do justice by me,” Nadesan wrote. “My transactions are transparent and matters of records.”

Nadesan denied wrongdoing and said that the case is based on a non-credible witness. The charges “amount to a travesty of justice,” he said.

Asiaciti officers placed Nadesan and his trusts under “high risk ongoing monitoring,” noting that the criminal case was “still in progress,” internal records show.In an Asian Tribune news article attached to a client review form, Asiaciti officers highlighted in yellow some details of the case, including that Nadesan was “barred from leaving the country.”

But the firm continued to work for Nadesan, managing his trusts and shell companies, which at that point held about $10 million in assets. Four years later, in 2020, Singapore’s financial authority would fine Asiaciti $793,000 for failing to implement anti-money- laundering policies and to identify clients at risk of committing financial crimes.

The goddess of wealth and prosperity

In the midst of the corruption investigation, Nadesan hired movers to transfer his London-based art to the Geneva Freeport.

As with other so-called free ports, clients of the 133-year-old Geneva Freeport, both individuals and companies, can store and trade goods held there without incurring customs duties or sales tax.

Anti-money-laundering experts say free ports are increasingly taking on a role played by private banks in protecting wealthy clients’ identity and financial dealings. Clients can use the Geneva warehouse complex, majority-owned by the Canton of Geneva, as a place to dodge taxes on their valuables and shield them from creditors and investigators.

Art traffickers have used the Geneva Freeport to hide crates of looted Roman and Etruscan antiquities, among other relics, and to launder money, according to Swiss prosecutors and the Italian police. (The Freeport’s managers have since implemented due diligence checks on antiquities, its chairman, David Hiler, told Reuters.)

In 2016, Swiss authorities seized a painting by Amedeo Modigliani after ICIJ’s Panama Papers investigation revealed that the $25 million painting had been stored for years at the Geneva Freeport under the name of a Panama shell company.

The painting, “Seated Man (Leaning on a Cane),” had remained hidden in a room in the Freeport managed by the Geneva-based art-storage company Rodolphe Haller SA. The same company stored Nadesan’s collection.

In late 2017, Nadesan requested that six works by 19th-century Indian master Raja Ravi Varma be set aside for his personal use, according to emails between Asiaciti officers and the art-storage managers. One of them was “Goddess Lakshmi.”

Nadesan’s advisers said he “hopes” to borrow the artworks from his trust, the owner on paper.

“If you’re trying to conceal your ownership through a trust, lending something to yourself makes it kind of look like you don’t own it,” Zarobell, the art expert, said. “That may just be a kind of sleight of hand.”

In January 2018, before the van-load of art arrived at the Freeport an employee at the Rodolphe Haller company opened a new account for Nadesan. The name on the account was not Nadesan’s or his wife’s but that of their offshore company Pacific Commodities Ltd., the leaked files show.

“Please note that for confidential [reasons] only authorised officers of [Asiaciti] can give instructions or be informed about the account,” the Rodolphe Haller officer wrote in an email.

Rodolphe Haller did not respond to ICIJ’s request for comment.

Nadesan instructed Asiaciti that upon his death, the art, as well as the apartments in London and Sydney, would belong to his two children, who in the meantime had obtained Cypriot citizenship, according to the leaked files.

A few months after the art transfer, a Sri Lankan media outlet reported that authorities probing Nadesan’s offshore holdings had discovered a Hong Kong bank account holding $22 million owned by a company linked to Nadesan named Red Ruth Investments Ltd.

The Pandora Papers reveal that the company had received annual loans of $140,000 from Rosetti Ltd., the Jersey company owned by Nirupama Rajapaksa and Nadesan. The records show Red Ruth then distributed funds to other shell companies and Nadesan’s Cook Islands trust.

Nadesan said that he was not aware of the authorities’ investigation into his company Red Ruth.

Back in power

At the end of 2018, the Sri Lankan government elected in 2015 began to crumble. Many in the Sinhalese majority opposed proposed constitutional reforms that appeared to threaten their prerogatives. The new president abruptly fired the prime ministerand installed presidential predecessor and former opponent Mahinda Rajapaksa – an attempt to benefit from Rajapaksa’s popularity, according to political analysts.

Parliament declared the appointment illegal and annulled it. But the political crisis turned out to be a boon for the Rajapaksa brothers. In November 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the former wartime defense chief, was elected president.

He promptly appointed Mahinda prime minister and dished out plum government roles to other family members.

In January 2021, the new president appointed a government commission to review criminal allegations – including land deal-related embezzlement charges against Nadesan – brought by the previous government against Rajapaska allies.

Over the objections of human rights advocates and other critics, the commission recommended the charges against Nadesan be dropped. The case is ongoing.

Contributors: Margot Gibbs, Echo Hui, Mario Christodoulou, Kentaro Shimizu