Sri Lanka’s prisons are holding more than double the number of prisoners they have capacity for and as a result prisoners are suffering under atrocious conditions. The vast majority are remand prisoners, also known as pre-trial detainees. They are unconvicted, not yet found guilty, but forced to live in the squalor and violent environment of remand prisons.

In 2023, 138,117 remand prisoners entered jails and on average there are 17,000 at any given moment. Sri Lanka has one of the highest rates of pre-trial detention in the world. The lucky ones are released on bail but about half spend more than a month in prison before being released, acquitted, or convicted.

Mr. Jagath (name changed), 30, who spent one month in remand said the experience was unbearable. “There were bed bugs everywhere and terrible food,” he said. “It was so crowded that there was nowhere to sleep properly. Our bodies were just inches away from each other and people got violent quickly.”

The Sunday Times was denied access to visit any of the remand prisons, citing “legal problems as the trials are ongoing’’. However, a 2023 report on overcrowding by the Auditor General and a 2020 Human Rights Commission Report shed light on the conditions inside.

The report showed that food, sanitation, and security were all inadequate.

Prisons are so overcrowded that prisoners have to take turns sleeping or sleep inside toilets as there is not enough space for all of them to lie down simultaneously.

Sanitation facilities are deplorable, with nearly all prisons facing a toilet shortage.

Mahara Prison tops the list, lacking 48 toilets to accommodate the nearly 2,000 prisoners — well above capacity.

Prisons are also hotbeds of drug use and violence, exposing potentially innocent remand prisoners to hardened criminals and gang members. Nearly half of prison admissions are on drug charges. From those awaiting to be sent to mandatory drug rehabilitation, to small scale dealers, to international drug smuggling dons, all meet and live together in remand prison.

Mr. Jagath said that in prison it was possible to access all sorts of contraband from mobile phones to alcohol, cigarettes and drugs. Ironically, Mr. Jagath was kept in remand prison awaiting mandatory rehabilitation.

So why does Sri Lanka have so many remand prisoners?

Firstly, bail is severely underused where magistrates regularly deny bail or do not give suspects sufficient time to present their bail applications. As a result many people who could have qualified for bail end up in remand, according to the HRCSL report.

Some people are also unable to post bail because they cannot afford the monetary sum or because they are arrested outside of their districts and cannot produce sureties (a relative or government servant who promises to make sure the suspect returns to court for trial).

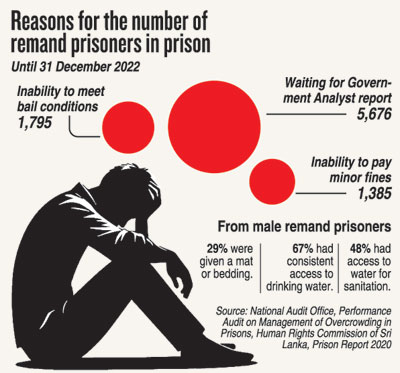

According to a report by the Auditor General on 31 December 2022, 1,795 people were in prison because they could not meet bail conditions — that is around 10% of the remand prison population.

Moreover, in drug cases, the possibility of bail is determined by the quantity of pure substance found on a suspect. To determine this, however, the substance has to be sent to the government analyst’s department where there are months long delays.

According to department officials, only samples collected up to April have been analysed and reports submitted. The official explained that due to a large number of vacancies in the department and partly due to ‘ Yukthiya’, police operations, over 34,000 samples have been sent to the department this year, but tens of thousands are yet to be completed.

Suspects waiting for their report will have to do so from prison. In 2023 over 5,600 were in remand awaiting a report. Although a parliamentary oversight committee looked into the problem in September 2023, the issue is yet to be resolved.

Prison overcrowding has lingered for years and a number of solutions have been put forward. In 1991, the government passed the Release of Remand Prisoners Act (RRPA) designed to release those who had not been able to post bail.

Robust implementation of the law was recommended by HRCSL to address prison overcrowding, but the act is underused and outdated. Robbery is an eligible offence for release under the RRPA, but because the act hasn’t been amended since 1991, only those accused of stealing less than Rs. 1,000 stand a chance of being released.

Gamini Dissanayake, the commissioner of prisons, said that sometimes people end up in prison because they have not been able to pay small fines. He said overcrowding is being discussed. “There are alternatives to imprisonment such as the use of the probation department. We are also considering house arrest and other ways.”