Amid international criticism of human rights abuses during the last stages of Sri Lankan government’s war against separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the government has stepped up its propaganda about the “resettlement” of war refugees. It insists that it has have “resettled” more than 90 percent of the refugees and claims they live in better conditions than before the war.

Three years since the end of the war in May 2009, however, “resettled” Tamils in the former LTTE-controlled Vanni in northern Sri Lanka are living in deplorable conditions. The following article was submitted by a WSWS reporting team that recently visited the area. Residents’ names have been withheld for obvious security reasons.

The WSWS reporting team visited Dharmapuram, a village badly affected by the war and located 13 kilometres east of Kilinochchi, along the Paranthan-Mullaithivu road. Following their resettlement, refugees were only provided with dry rations for six months and now, without proper jobs or an income, often go without food for days at a time.

The first generation of villagers were Tamils from central Sri Lanka’s plantation districts who had fled anti-Tamil communal riots in the 1950s. Their descendants later mixed with war refugees from the north and east in the 1990s. Dharmapuram residents fled to the Mullaithivu district during the last stages of the war. Dharmapuram village was captured from the LTTE by the Sri Lankan military on January 15.

A typical resettlement hut in Dharmapuram

A typical resettlement hut in Dharmapuram

Most people are still living in huts made from tarpaulins issued by the UNHCR. Since then they have been given eight tin sheets per family to use for roofing. Each hut is just 8 x 8 feet with only one room, which is used as a bedroom, kitchen and lounge. It is impossible to remain inside the tiny huts on hot days. Residents have no permanent work and attempt to survive as daily wage labourers.

While a handful houses were constructed with government aid, most of the residents were not provided with homes. While a new home cost over 600,000 rupees, the government only provided 325,000 rupees ($US2,470) per house with residents expected to take out loans to finance the rest of the construction.

As one woman explained: “The government promised 325,000 rupees [for a house] but we only received only 225,000 rupees. We pleaded with authorities to grant the rest but they said they would only give us the balance after the house was completed. How can find the balance when we are struggling just for a daily pot of porridge?”

Her husband added: “I go to the junction and wait for any work every day. If anyone hires me I get an income to feed my family. If they don’t, then we starve or get indebted to the shop owner. We only have one meal a day and some days we don’t even have that.”

A mother of three daughters who lost her husband 13 years ago said: “I didn’t get any government aid for a house. When I asked the authorities, they said that if a housing scheme plan comes along they’d provide aid. There are so many people who don’t even get that far.

“I have no permanent job. I used to farm with my father’s help but that’s no longer possible because the landowners are demanding more rent for use of their land. If I agreed to pay this rent I’d have to toil and toil but in the end still have nothing in my hand.”

Like several other residents, the woman was given 50,000 rupees by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) to establish a poultry farm—20,000 rupees as a subsidy and 30,000 rupees in the form of a loan to be paid in 10 months. Disease, however, killed all the poultry. There is no veterinary surgeon in the area.

Although they pleaded with the IOM to write-off the loan, aid agency officials insisted the money be repaid. “We had to borrow on higher interest to settle the loan. We wanted to provide for ourselves but in the end we became debtors. That’s the only thing we gained,” she said.

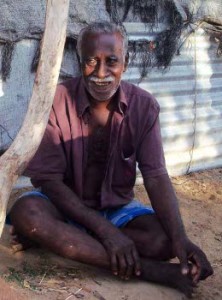

A Vanni resident outside his hut

A Vanni resident outside his hut

Villagers also face water shortages. There are a few wells in the area but no running water facilities. To dig a well they need at least 200,000 rupees. Many families are forced to use a small pond for bathing and clothes washing. The same pond is also used by animals, increasing the risk of local villagers catching water-borne diseases. There are no toilet facilities and there is no electricity. Unsafe bottle lamps are used for light with children attempting to study in the dim light.

Although the village school has classes up to university entrance, lack of teachers, particularly for Science and Mathematics, means that students need private tuition. Those who want to study science or mathematics for university entrance have to go to Jaffna or Kilinochchi.

The small government hospital at Dharmapuram is overstretched and lacks basic equipment and staff. It also serves people from the neighbouring villages of Kalmadu, Vattakachchi, Udayarkaddu and Vishwamadu.

While the government has banned hospital staff from talking to the media about the facility, one hospital employee explained: “This hospital needs six doctors but there’s only one doctor serving here. The beds are inadequate and there’s no laboratory here for medical tests. There are not even facilities to check for malaria.”

A 22-year-old mother, who was critically injured twice by bombs during the war, said: “My whole body has injuries. I have a bullet in my chin and visited Kilinochchi and Jaffna hospitals to get it removed. They told me to visit Colombo but I need 200,000 rupees for that treatment. My husband lost his left hand in a shell attack and his right eye was also severely injured. He can’t do heavy work so we have no money for the treatment we need?”

Elderly residents who lost their family breadwinners during the war are desperately struggling for food each day. Eighty-year-old Pilippiah Rasanayagam, lost his 30-year-old son in a military shell attack in 2009. Pilippiah and his wife are living at Pannakandy in Kilinochchi. He has been forced to beg for their meals from neighbours who are also living in poverty.

All those we spoke to were bitter about their desperate conditions and voiced their hatred of all the political parties. “Those parties only come to us only for votes,” was a common refrain.

One woman said: “Geethanjali [a Kilinochchi district organiser for the ruling Sri Lanka Freedom Party] visits here. She’s always talking about a ‘better life for women’ and attempting to collect people for their meetings, but she does nothing useful for us.”

Another villager spoke about the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), Sri Lanka’s main Tamil bourgeois party. “They only come here to get our votes but they’re useless. In the last elections, we voted for them and after that they never visited here.”