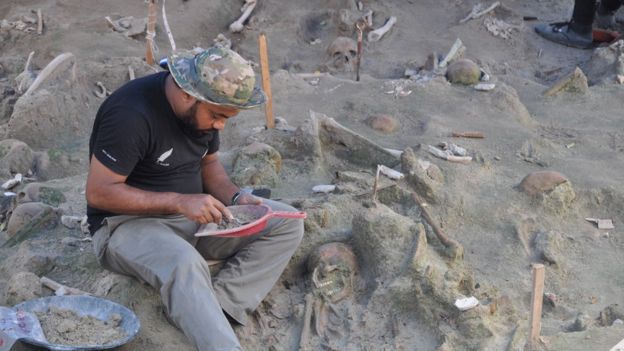

Image:Forensic archaeologists were brought in after building workers unearthed human remains.

So far the skeletal remains of more than 90 people have been unearthed in the north-western town of Mannar.

The mass grave is the second biggest found in the north since the end of the conflict in 2009.

The 26-year war between troops and separatist Tamil rebels left at least 100,000 people dead, and many missing.

A court ordered detailed excavations at the site – a former co-operative wholesale depot near the main bus terminus – after human remains were found by workers digging foundations for a new building earlier this year.

“The entire area can be divided into two parts. In one segment we have a proper cemetery. In the second part, you have a collection of human skeletons which have been deposited in an informal way,” said Professor Raj Somadeva, a forensic archaeologist from the University of Kelaniya near Colombo, who is leading a team of experts at the site.

There is more ground still to excavate and he says more skeletons could be found. The remains unearthed by his team include the skeletons of at least six children.

Who the victims were – and who killed them and when – remains unclear. The town of Mannar is dominated by ethnic minority Tamils.

Local police guard the site so no-one can tamper with it and the forensic archaeologists can painstakingly remove skulls and other bones from the dirt without being disturbed. They use brushes and small chisels so the remains are not damaged.

No clothes or other items have been found in the grave that could help identify the victims.

While Mannar town remained mostly under army control during the civil war, Tamil Tiger rebels dominated its surrounding areas and many other parts of the district. The military captured the entire district after ferocious battles, which ended almost 10 years ago.

The way the bodies are arranged inside the mass grave has puzzled the experts.

“We are concerned about the line position. [It is] completely chaotic – you have two layers of skeletons roughly,” said Prof Somadeva.

As his team uncovers the human remains, they transfer them to the custody of the court in Mannar, which will decide the future course of action once the excavation is complete.

Prof Somadeva and his colleagues are also yet to determine how the victims died. The age of the bodies will be analysed later.

So far no one has been blamed for the killings.

A number of mass graves have been unearthed in Sri Lanka’s former war zone since the conflict ended.

None found so far has contained more bodies than a site in another part of Mannar – adjacent to Thiruketheeswaram, a prominent Hindu temple – where the remains of 96 people were discovered in 2014.

But four years on there’s still no clarity in this case either, about who was killed and by whom.

Rights groups allege that both the military and the Tamil Tigers inflicted widespread civilian casualties. At least 20,000 people disappeared during the conflict.

But the government has always denied its forces had anything to do with civilian deaths or disappearances.

After years of international pressure, the government set up an independent body, the Office of the Missing Persons (OMP), earlier this year to investigate the disappearances. The OMP has provided partial funding for the excavation in Mannar.

OMP chairman Saliya Pieris insists that a detailed investigation at the latest grave found in Mannar is important.

“The primary task of the OMP is tracing the disappeared and informing the relatives about the circumstances of their disappearances.

“One of the aspects of this tracing would be naturally [to find out] if there are mass graves and there are people who have been disappeared, who have been buried in mass graves.”

But given the failure of the authorities to investigate the remains unearthed from previous mass graves, there is scepticism among Tamils over what the new inquiry might achieve.

“Hundreds of people disappeared in Mannar district during the conflict while moving from uncontrolled areas to controlled areas,” said Victor Sosai, vicar general of the Catholic Diocese of Mannar.

“There have been allegations that several Tamils who were trying to flee the conflict to India on boats were also intercepted and their fate is unknown.”

He visited the site of the latest mass grave along with the Bishop of Mannar, Emmanuel Fernando, during the initial stages of the excavation.

“We understand that they have found skeletons of children and adults, we need to really find out more about who these people are and how they died and who was responsible,” Rev Sosai says.

The Tamil Tigers were accused of ruthlessly eliminating fighters and supporters of rival Tamil militant groups. They were also accused of executing Sri Lankan soldiers captured in battle.

But the army dismisses any suggestion that soldiers are connected with the bodies found in the mass grave in Mannar.

“Definitely there is no link between this grave and the army. No one has accused the army so far,” said army spokesman Brig Sumith Atapattu.

But many in the minority Tamil community say if Sri Lanka really wants to come to terms with its past, then it has to sincerely address the issue of the disappeared by investigating mass graves.

Only then might the families affected be able to properly grieve and try to move on.