The mob violence that suddenly burst forth in Jaffna has given rise to multiple interpretations, both in Jaffna and elsewhere. Opposition politicians have claimed that the displaced Sinhalese who have been resettled in parts of Jaffna were being targeted. Others claimed that national security had been jeopardized by the demilitarization taking place in the North and the entrusting of security measures to the police. They saw in the unrest the footprint of the Tiger seeking to stage a comeback with support from parts of the Tamil Diaspora who continue to harbor separatist ambitions. In these analyses of the happenings in Jaffna there seemed to be a certain nostalgia for a return of the old days when the former government of President Mahinda Rajapaksa ruled the North with an iron hand. But this was not the reality in the North nor the desire of the people there.

The mob violence that suddenly burst forth in Jaffna has given rise to multiple interpretations, both in Jaffna and elsewhere. Opposition politicians have claimed that the displaced Sinhalese who have been resettled in parts of Jaffna were being targeted. Others claimed that national security had been jeopardized by the demilitarization taking place in the North and the entrusting of security measures to the police. They saw in the unrest the footprint of the Tiger seeking to stage a comeback with support from parts of the Tamil Diaspora who continue to harbor separatist ambitions. In these analyses of the happenings in Jaffna there seemed to be a certain nostalgia for a return of the old days when the former government of President Mahinda Rajapaksa ruled the North with an iron hand. But this was not the reality in the North nor the desire of the people there.

I travelled by train to Jaffna two days after the civil disturbances in Jaffna and hartals had shut down parts of the North. The day I reached Jaffna there was a court order that banned any public protests. The area close to the courts complex had been sealed off by the police. As a result television footage of that part of Jaffna would have given the impression that the city was empty and military control was high. There was a large contingent of military personnel on the streets. But they stood by, and made no attempt to interfere with the ordinary life of the people which continued in the rest of Jaffna. The general population seemed accustomed to their presence, which had become a part of the natural landscape during the previous decades.

My Muslim colleague and I went to lunch in a Muslim “hotel” or more accurately roadside eatery located on a side road. I asked my colleague to start a conversation with a diner at the next table whom I assumed was a Muslim and who would therefore be conversant in the Tamil language, and find out what he thought of the current situation. To our surprise the person who was addressed in Tamil replied in Sinhala and said he was Sinhalese. It turned out that he was a worker at a bakery in Jaffna. He said he was from Matara, but had come to Jaffna as the price of bakery products was higher in Jaffna than in Matara, so he could make a better living here. He sold bakery products by going house to house on a motor cycle which had been made into a delivery vehicle. He said he and his friends had faced business reprisals five years ago when they first started their business venture, but now it had all settled down. He did not feel threatened.

POLICE INACTION

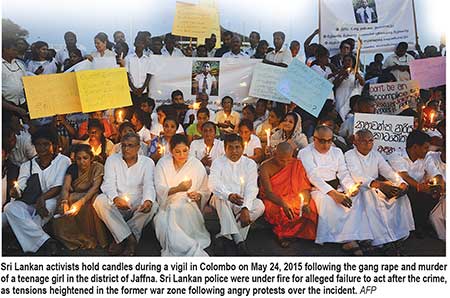

The mob violence in Jaffna arose after the rape and murder of a teenage girl in one of the small islands off Jaffna. The initial public anger was directed against the police who had been slow to act on the complaint of the family members of the girl. Like in the rest of the country, there is a sense of frustration within the community that too often the police do not work as quickly and efficiently as they should. In this instance, the police reaction had been to not take the complaint seriously and to be jocular and say that the girl had probably gone on a rendezvous with a boy. The family and larger community felt that if the police had acted earlier the girl’s life might have been saved. In fact it was the brother of the girl who had found her body after he had searched the area that she usually walked on her way to school.

There has been a longstanding complaint emanating from the people of Jaffna that when robberies of their homes, and rapes of their women take place, the police are inactive. While they do not accuse the police as being the culprits, they sometimes doubt whether the police is in connivance with the wrongdoers and being paid off by them, as the reasons for their inactivity. The deficiencies in the police are more aggravating to the people of the North as most of the police officers in Jaffna, and indeed the North, are Sinhalese from far away, and not Tamils from the same community. In more democratic countries like those in Europe where participatory democracy is valued, the local police are usually drawn from the community themselves and not from far away.

The civil society members I spoke to in Jaffna said that it had been civil society groups, such as the Teachers Unions and university students that had organized the shutdown of normal life for a day of protest against the failure of the law enforcement agencies to be more effective in protecting the people. However, they do not believe that these groups planned anything violent, such as the throwing of stones that damaged the courts complex and nearby commercial establishments. During the public protests a section of the crowd had turned violent and resorted to stone throwing which led to police firing tear gas and a general commotion. The civil society members I spoke to were convinced that there was a political hand behind those who acted violently, and they had their theories.

POLITICAL MOTIVES

With the President announcing that a new government will be in place by September and the indications that general elections are fast approaching, all political parties and potential candidates are busy mobilizing their forces or planning to do so. One of the interpretations in Jaffna regarding the identity of those who threw stones and behaved in a rowdy manner unbecoming of a civil society is that that they were politically organized groups with a political agenda. The allegation is that there is a section of the polity that wishes to create a general impression that the North continues to be unstable and volatile even six years after the end of the war, and therefore needs a strong hand and a powerful military machine to control it. After the events in Jaffna there were politicians with a nationalist orientation who said that the events in Jaffna demonstrate that the country needs a political leadership that will not betray the country or its armed forces whose grip over the North should not be relaxed.

Those who continue to speak and adduce arguments for a strong government and military presence in the North are challenging the most fundamental achievement of the new government led by President Maithripala Sirisena. This is the restoration of civil administration to the North and East, symbolized by the removal of the two governors of those provinces who were from military backgrounds, and replacing them with governors with purely civilian backgrounds. As a result the pervasive sense of fear and insecurity that underlay social and political life in the North of the country has been lifted. This is acknowledged and appreciated by the civil society in the North. Indeed, this fear has been lifted throughout the country, due to the restoration of the rule of law, and the banishing of the culture of white vans that took people away with impunity.

In the not so distant past, the former government dealt with civil unrest and mob action with extreme violence whether in the North or South. This was seen both in the free trade zone protest by garment factory workers and in Rathpaswella when villagers protested against the contamination of their drinking water by industrial waste. On both occasions the military was used to violently break up the protests with loss of life. However, on this occasion, the government succeeded in quelling the Jaffna unrest without resorting to violence. The government showed that it would not brook lawlessness and took about 130 persons into custody. The civil society members I met in Jaffna felt that many of those arrested were not engaging in violence and were there to protest peacefully, and hope that the courts will release them soon. They also appreciated the fact that there had been no overreaction on the part of the security forces that could have set a vicious cycle in motion.