Sri Lanka’s raffish capital, where we begin our series, is in economic catch-up mode. Colombo is replacing the colonial-era roads and railways built when Churchill was a boy and ‘Ceylon’ was a languid tropical afterthought for the British who ruled the plantation island.

|

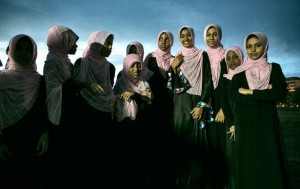

| Muslim students from an Islamic school in Colombo watching for the moon – when the first day of Ramadan will begin. |

Though it took its time – 10 years – to be completed, a sparkling new tollway to the beachy Rajapaksa heartland in the south has cut the journey from Colombo from a congested three-to-six hours to just one.

In the conflict-ravaged Tamil north, Indian engineers are re-connecting the war-severed train line that once carried passengers from Colombo to Jaffna.

In the mostly Sinhalese ‘deep south’ of the island, President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s home region of Hambantota is being lavished with the country’s biggest infrastructural project, a US$1.5 billion stampede of white elephants that’s giving the town a new port, international airport and cricket stadium – all named after President Rajapaksa – and a convention centre and even an alternative Bollywood complex.

|

| A Korean-financed convention centre rises in the President’s home turf of Hambantota, one of the town’s many mega-projects keeping some Sri Lankan and many foreign construction workers employed. |

Beijing is the main player behind all this construction, as it adds yet another stronghold to its string of pearls – China’s network of strategic boltholes around the Indian Ocean intended to counter Western commercial influence in the region. Beijing financed most of the Hambantota projects and shuttles Chinese workers in to build them; this in a region suffering crippling unemployment.

In Colombo, work has started on a Dubai-style ‘Port City’ – replete with de rigueur Formula One circuit – to be built on land Chinese companies are reclaiming from the sea. In November this year, all this will be flaunted in a diplomatic coup for the Rajapaksa regime – Colombo is hosting the biennial Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM).

Colombo may still be one of Asia’s poorest capitals, but its Rajapaksa-linked business community is re-arranging the skyline on borrowed money. It is studded with the new skyscrapers of hip hotels and soaring towers in various states of completion, which they hope will be filled by the ambitions of international tycoons. Australia’s James Packer, for example, has teamed with a Rajapaksa crony to build a US$350 million casino complex here.

But of the many towers now poking through Colombo’s fast-fading colonial vista, few have gone up as fast or been fêted with as much official attention as the Sri Sambuddhathva Jayanthi Mandiraya, a massive temple and office complex now soaring over the capital’s leafy southern suburbs.

Opened in 2011, just two years after the war ended, the complex claims to be the world’s biggest repository of Buddhist texts. Its modern foyer has the air of a busy library, criss-crossed by orange-hued tourists and locals in search of their inner Gautama. Less advertised, however, is that an adjacent wing is home to the headquarters of a shadowy ultra-Buddhist activist group called Bodu Bala Sena, which was formed in July 2012.

Bodu Bala Sena general secretary Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara reaches out to the protesters.

That translates as the “Army of Buddhist Power”. Patronised by senior government officials, the BBS was born after militant fringes of the main religious party in Sri Lanka, the Jathika Hela Urumaya (JHU), or National Heritage Party, broke away because they felt the JHU was too moderate.

THE BBS CHOOSES TO SEE ANTI–BUDDHIST DEMONS WHERE NONE EXIST.

Since then, the BBS has emerged as the self-proclaimed true protector of Buddhism on the island, and many say it chooses to see anti-Buddhist demons where none exist. Sri Lanka may be at peace, with Sinhalese Buddhists in command and a pious and powerful practising Buddhist in the presidency, but to hear the BBS hierarchy tell it, Buddhism and Sri Lanka have never been more at risk.

Part vigilante group, part religious police, partly a Sri Lankan Tea Party, the BBS has been behind many of the attacks on Muslim practices and businesses here, and on Christian groups too, often encountering little police intervention. BBS members make mostly unchallenged claims, on scant evidence, that Muslims dominate Sri Lanka’s business community and foment religious fundamentalism, and that Muslim doctors secretly sterilise Sinhalese women. The group has also taken aim at Christians, warning churches against expanding their flocks by converting Buddhists.

Secularist Sri Lankans are alarmed. Social Integration Minister Vasudeva Nanayakkara has described the BBS as “extremist”. Prominent Sri Lankan diplomat Dayan Jayatilleka labels it as an “ethno-religious fascist movement from the dark underside of Sinhala society”, while the island’s most prominent Buddhist intellectual, the Venerable Professor Belanwila Wimalaratana Anunayake, has dissociated Sri Lanka’s sangha, the mainstream Buddhist clergy, from BBS extremism.

Tamil leaders are also concerned. “I think this is a game that they are playing,” says Kumaravadivel Guruparan, law lecturer at Jaffna University and civil-society activist in the war-ravaged north-east. “We thought you can’t get more Sinhala Buddhist-extremist than this government,” but then groups like the BBS suddenly emerged on the government side – “so now they [the Rajapaksa regime] start looking like a moderate”.

|

| President Mahinda Rajapaksa graces the official opening of a centre built in the name of his astrological adviser, the Sumanadasa Abeygunawardena library in Galle. |

The post-war rise of militant Buddhism in Sri Lanka, which mirrors similar activism in reformist Burma and elsewhere in South-East Asia, has particularly sinister overtones here.

One of Sri Lanka’s most controversial post-colonial dynastic leaders, Solomon Bandaranaike, was assassinated in 1959 by a Buddhist monk who felt betrayed that Bandaranaike’s pro-Sinhalese policies – which many Sri Lankans believe sparked the separatist Tamil uprising in the north-east – didn’t go far enough to advantage the Sinhala-speaking majority. (There is another view that the assassin, who converted to Christianity before his execution, was hired by a senior monk avenging the loss of business opportunities.)

The BBS’s layman chief executive and program co-ordinator of its Buddhist Leadership Academy, Dilanthe Withanage, met The Global Mail at the group’s nerve centre, a bland suite of offices that wouldn’t be out of place in the new corporate Sri Lanka.

A nuggety man in his 40s, Withanage wears civilian garb, in contrast to the orange-robed monks drifting through the office. He speaks English and Russian – by virtue of his Soviet-era-sponsored education in Georgia.

According to Withanage, the BBS came into being because “we felt that Buddhism is not protected in this country and Buddhists face a big danger locally as well as internationally”. This despite the fact that as many as 75 per cent of Sri Lankans identify themselves as Buddhist Sinhalese.

Many Sri Lankans believe that the BBS is a creation of the government, in particular of President Rajapaksa’s brother Gotabaya, Sri Lanka’s unelected Defence Secretary, a former soldier and the mastermind of the 2009 victory over the mostly Hindu Tamil rebels. Gotabaya has denied any involvement in the emergence of the BBS.

The BBS seems to be a Lankan re-run of India’s ethnocentric Mumbai-based Shiv Sena movement; and of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the National Patriotic Organisation of Hindu extremists, which shadows India’s nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party.

Withanage rejects such comparisons. “We don’t have any political influence,” he claims.

But if the president’s powerful brother is not an architect of the BBS, Gotabaya Rajapaksa seems at the very least to be a patron of the organisation. In March, he officiated at the opening of a BBS outpost in the southern port city of Galle, which has a big Muslim community centred on its ancient fort.

But that’s not quite how the “German fellow”, a Buddhist called Michael Kreitmeir, sees it. He told The Global Mail his ‘Meth Sevena’ retreat outside Galle, set up in 2007 as part of his interfaith charity, Little Smile, had recently become embroiled in an ownership dispute. He said he had approached the Buddhist Cultural Centre in Colombo for co-operation, but was “most surprised” to discover it had “some connection” with the BBS, and that Gotabaya Rajapaksa then showed up to open his project. “Meth Sevana is not and will never be a centre of Bodu Bala Sena,” Kreitmeir says.

Earlier this year, when Milinda Moragoda, an erstwhile presidential advisor and leading figure in Colombo’s civil society lobby, brokered a cross-religious community deal over cattle slaughter and the halal certification of food products, Buddhist and Muslim leaders linked hands in a public display of unity.

But the Moragoda deal fell short of the blanket ban on halal labelling demanded by the BBS. Outraged, the BBS then accused Moragoda of creating “an unholy inter-religious alliance, and attempting to destroy our learned monks [who were] now in the grasp of infidels”. These monks, the BBS lamented, “were pseudo Buddhist leaders who never stood against Muslim extremism and Christian fundamentalism”.

For his part, Morogoda told The Global Mail, “as a practising Buddhist … in my view, true Buddhism is all about the Middle Path, moderation and tolerance. That is the Buddhism that I follow. Extremism is antithetical to the teachings of the Lord Buddha who preached moderation and tolerance. There is no need for self-proclaimed protectors of the doctrine.”

GNANASARA TURNS VERY ANGRY AT THE MERE MENTION OF MUSLIMS AND ISLAM, WHICH IS HARDLY THE DEMEANOUR ONE EXPECTS OF A PIOUS BUDDHIST MONK.

“RELIGION is a private thing,” Withanage tells The Global Mail. And many conflict-weary Lankans would agree.

But in recent months Withanage’s group has chosen to make some very public religious protests.

In January, the BBS hierarchy got hold of an event-planning document for a dinner that was to be hosted at a resort hotel south of Colombo. The hotel is much favoured by French tourists and owned by Sri Lanka’s biggest company, John Keells Holdings.

Keells is a sprawling enterprise, straddling interests in IT, banks, plantations, hotels and retail, and is as yet outside the expanding corporate grasp of the ruling Rajapaksa clan. Businessman Susantha Ratnayake is chairman of Keells, and also chairs the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce (CCC), which had helped to broker the inter-faith halal deal with Moragoda and the various religious lobbies. Ratnayake and the CCC have since been in the BBS’s crosshairs, because the BBS claims they “fail to safeguard” Buddhist business interests on the island.

The Keells document that fell into BBS hands discussed the theme the hotel staff had planned for the dinner; it described the meal as “nirvana” with a “cosy Buddha Bar lounge” feel. Intended for French holidaymakers, this function seemed intended to evoke the Parisian music and food phenomenon fashionably fused by French-Tunisian DJ Claude Challe, which became the chill-out soundtrack of the 2000s for hipsters from Bali to Budapest.

But the BBS response was anything but chilled. An orange army of militant monks led by the group’s secretary-general, Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara, stormed the hotel and succeeded in having hotel management carted off by the police on a charge of “hurting religious feelings”.

The BBS moved on the hotel, Withanage told The Global Mail, “because of the alcohol, the dancing, the behaviour”.

When asked whether the BBS is against people having a good time, Withanage railed: “Why do they use the menu ‘Nirvana’? The name Buddha should be used appropriately. We should respect any religion. The context is different, it’s not appropriate to use in a hotel, in the evening party.” He adds that calling a drinks venue “the Jesus Bar” might similarly be deemed hurtful by Christians.

Although a self-appointed guardian of public morals, the BBS is oddly unfussed by the plethora of casinos in Sri Lanka. Many of these are owned by business associates of the Rajapaksa clan, including the government-approved $US350 million development planned by local tycoon Ravi Wijeratne and Australian James Packer on a prime downtown Colombo site, which happens to be adjacent to Colombo’s oldest Hindu temple.

“Lord Buddha is not against anything,” says the BBS executive Withanage, when asked about this apparent moral inconsistency. “He never asked kings to stop things.”

Prayers: Sunday Mass at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Jaffna

and evening Ramadan prayer at the Jumma Mosque in Colombo.

“In Sri Lanka, there are a couple of casinos. No-one protested about them,” he says. “But when this Australian guy wanted to start, they all talk about casinos. What we [the BBS] said was if we attack that person, we should attack the other parties also.

“If we want to stop casinos, it’s everybody,” Withanage says. “We should not attack only one casino because that turns us into being against investment. If you’re against casinos you should be against all casinos in the country.”

“Personally, I think it is better that we don’t have gambling but we [BBS] don’t have any problem with it,” he says.

The BBS would, however, like Buddhism to be Sri Lanka’s official state religion. The current constitution, passed in 1978, holds that Sri Lanka is a secular state guaranteeing its citizens freedom of religion, with Buddhism holding the “foremost place”. There is no mention of Hinduism, Islam or Christianity in the document.

The BBS claims Buddhism was the island’s state religion before the British colonised ‘Ceylon’ in 1815 after deposing its Kandyan aristocracy. “We think whatever we had before the British should come back,” says Withanage.

Hinduism has been practised by large numbers on the island for millennia, and today as many as 15 per cent of the island – Sri Lanka’s Tamil communities – lay claim to being Hindu. Its presence on the island is even mentioned in the epic Hindu poem, the Ramayana, which dates from around the 4th century BC. Hinduism was also the state religion of the Jaffna Kingdom in the north of the island that fell to Portuguese invaders in 1624.

But that doesn’t seem to factor in the BBS’s version of history. Withanage rules out Hinduism as a co-state religion in Sri Lanka, and any official recognition for Islam and Christianity too. “Before the British came into this country, Buddhism was the state religion so therefore Buddhism should be the state religion … provided all other religions have due respect and freedom to practice.”

A tall 40-something man in a luxuriant vermillion robe and furiously tapping at an iPad joins us. He exudes authority, and Withanage stops mid-sentence to genuflect to the newcomer. I recognise him as Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara, secretary-general of the BBS and one of the group’s founders.

|

| Bespectacled BBS general secretary Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara addresses a protest outside the Indian High Commission in Colombo, following a recent attack on the Bodhgaya temple in India.Add caption |

Withanage introduces him and they continue railing about the real or imagined threats to Sri Lankan Buddhism. I ask them why they see their faith as under threat on an island where ethnic Sinhalese Buddhists comprise around 75 per cent of the country’s 20 million people – leaving Sri Lanka’s other ethnic and religious groups clearly in the minority – and given that the president is a very publicly devout Buddhist and a vocal champion of the faith.

It’s not just Sri Lankan Buddhism that the BBS is campaigning for, Gnanasara explains, but for others in the Buddhist world too. He cites the recent banning from circulation of an issue of Time magazine in Sri Lanka, because it described the outbreak of Buddhist militancy in nearby Burma as ‘The Face of Buddhist Terror’.

I ask about recent attacks on Muslim interests blamed on the BBS. The men deny that the BBS attacked a prominent Muslim-owned clothing chain, Fashion Bug, in suburban Colombo, as was widely reported in Sri Lanka, even in the government-owned media.

Gnanasara turns very angry at the mere mention of Muslims and Islam, which is hardly the demeanour one expects of a pious Buddhist monk. Withanage’s previous, more moderate explanations of BBS activism now pale before a bilious Gnanasara who seems to rail at the notion of anyone who isn’t a Buddhist.

“Don’t talk with us,” Gnanasara yells. “Any Muslims, they are very bad people here. They are creating all problems here.”

All Muslims? I ask.

“Yes, all Muslims same!” Gnanasara yells. “No chance here! We want to stop this extremist work of Muslims. They are not going to destroy our culture. Buddhist people are very peaceful.”

Withanage chimes in, insisting that Sri Lanka’s Buddhists have been very tolerant despite what he sees as the cultural provocations around them: “Muslims are living peacefully, Muslims have all facilities here. The mayor of Colombo is a Muslim,” Withanage declares. “Do you allow in your country a Muslim to be a mayor?”

Yes, I answer, Australia has a number of elected public officials who are Muslim.

But Withanage is unconvinced. “The governor of this province is a Muslim so you can’t say Muslims can’t live peacefully?” he says.

I remind him that I didn’t say that, but that his boss, the BBS secretary-general Gnanasara, did barely a minute earlier, insisting that all Muslims were bad. I ask Gnanasara about Hindus? Christians? Foreigners? Does the BBS have any problems with them?

“We are against only extremist groups, and fundamentalists,” he says.

What about Buddhist fundamentalists, I ask?

“Where?” Gnanasara asks.

“Maybe here?” I suggest. I cite the remarks of various prominent Sri Lankans in civil-society circles, such as the diplomat and intellectual Dayan Jayatilleka and the politician Milinda Moragoda who negotiated the halal compromise. Both have publicly condemned BBS extremism.

“They are mad people,” he says. “Very bad people. They get funding from various people, Christian and other groups, to speak against Buddha, with NGOs.”

I cross-check, asking: So Jayatilleka, a career diplomat and Sri Lanka’s former UN ambassador, and former Minister Moragoda are mad?

“A very bad man he is,” snarls Gnanasara. “They are funded. You look at their background. Are they Buddhist? There are some groups created by the church and they want to destroy Buddhist culture. His [Jayatilleka’s] background is not Buddhist, Milinda is not Buddhist.”

Moragoda, however, had said: “As a practising Buddhist it would be improper for me to directly comment on a statement attributed to a member of the Buddhist clergy.”

President Rajapaksa charms them at the astrology centre.

Is President Rajapaksa a good Buddhist? I ask Gnanasara. And what of his brother Gotabaya, the Defence Secretary?

Gnanasara pauses, and smiles. “Yes, yes,” he says, his anger suddenly dissipating. “His [President Rajapaksa’s] wife is a Catholic, no?”

I think so, I say. Is that a problem?

“Very good,” he offers. “No problem.”

Translating Gnanasara’s Sinhala into English, Withanage says that Western media and other foreigners “like to attack Sri Lanka because we are a poor people, we are a small country, threatened by international pressures. And media, because you have money, you can travel. We would also like to come and interview your Prime Minister, but we don’t have money and you have enough money to do that.

“International media … have an agenda to destroy Buddhism and show the world that Buddhists are extremists, but when your prime minister talks about extremist ideas in Australia no-one talks about these things. Please fund us, so we can show that.”

“We don’t trust the foreign media,” adds Gnanasara, via Withanage. “Most of you come with hidden agendas. A lot of false information about BBS is spreading around the world.”

The latest media report to upset the BBS leaders came from Xinhua, the Chinese state news agency. China has essentially kept the Rajapaksa regime afloat since 2005, financing huge infrastructure projects in the President’s home region of Hambantota, and providing much of the military matériel used by his military to conquer the Tigers.

But on July 8, Xinhua reported that BBS had demanded a ban on the wearing of the Muslim hijab in Sri Lanka.

Withanage says the Chinese are wrong. Citing similar laws in Europe, he says the BBS isn’t seeking a specific ban on the wearing of hijab in Sri Lanka, but a general public ban on anyone covering their faces. “We also don’t need that here,” he insists.

The fact that pretty well the only Sri Lankans culturally inclined to cover their faces on the island are members of its Muslim community is incidental, he claims, a mere coincidence. “This has nothing to do with religious matters,” Withanage insists. “We never talk about the hijab. We don’t have any problem with that.”

I ask Withanage why the BBS is staging regular mass protests outside the Indian High Commission in downtown Colombo.

“Because India should protect Buddhist heritage,” he says.

What hasn’t India done? I ask.

Withanage cites the July 7 bombing attempt at the holy site in Bodhgaya, in the Indian state of Bihar. Without any compelling evidence, South Asian politicians have variously blamed the bombing on Islamists from India and Pakistan, extremist Hindus and India’s militant Maoists. Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister himself has pinned responsibility for the bombing on diaspora remnants of Sri Lanka’s defeated Tamil Tiger separatists.

“This is the birthplace of Buddha,” Withanage says of the Bodhgaya site. “And it should be protected.”

There’s a problem with his assertion, a possibly revealing anomaly, given that the BBS styles itself as Sri Lanka’s true protector of the Buddhist faith. Even the humblest Buddhist would know that Bodhgaya isn’t Lord Buddha’s birthplace. It is widely agreed that Gautama was born in present-day Nepal. Religious archaeologists have cited a number of other possible locations in India and Nepal as his birthplace, but none in Bihar.

To Buddhists, Bodhgaya is where Gautama attained enlightenment. The holy site in Bihar may be regarded as the place where Buddhism was founded, but that’s a very different thing to the BBS’s position, and Withanage’s justification for the disruption outside the Indian mission.

Buddhist monks perform a traditional dance at a monastery in Bodhgaya, India, known as the place where Gautama Buddha obtained enlightenment-pic courtesy: STRDEL/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

I ask Withanage whether Tamil, the mother tongue of the island’s Hindu Tamil and Muslim communities, should continue to be an official language alongside the Sinhala spoken by Sri Lanka’s majority Sinhalese Buddhists. It was the Sinhala Only Act of 1956, enacted soon after what was then Ceylon attained independence from Britain, and which failed to officially recognise the Tamil tongue spoken by around 25 per cent of the population, which many Lankans believe led to the long-running separatist war in the Tamil north.

Four years after fighting ended, and with Sinhalese nationalism rampant, the language issue has again reared its head. There are indications that the Rajapaksa regime wants to dilute the so-called ‘13th Amendment’ of the constitution which currently guarantees Tamil equal status with Sinhala as an official language.

Gnanasara fudges an answer. “I think you need to understand history … you can’t just ask questions like this.” Withanage pipes up again: “We don’t have any issue with Tamils. Next month we will organise a large number of rallies in Tamil areas. The Tamil people want us there.

“We have never killed Tamils. We killed terrorists.” Withanage doesn’t elaborate on who the ‘we’ that he’s referring to are.

The monks wind up the interview. I prepare to leave, and Gnanasara barks brief and urgent instructions to Withanage in Sinhala. Withanage catches me up on my way out.

“When he said that all Muslims are bad …” explains Withanage “… that was a joke. We don’t have anything against Muslims.”

He then claims Gnanasara’s remark that “all Muslims are bad” was my fault, because I, the embodiment of the despised foreign media – as painted by the BBS – raised the subject.

Sri Lanka still has a long way to go before it can claim to be Paradise. courtesy: theglobalmail.org/DBS