ECONOMYNEXT – After working 11 years in Saudi Arabia as a driver, Sanath returned to Sri Lanka with dreams of starting a transport service company, buoyed by Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s 2019 presidential victory.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and an unprecedented economic crisis in 2022 shattered his dreams. Once an aspiring entrepreneur, he became a bank defaulter.

Facing hyperinflation, an unbearable cost of living, and his family’s daily struggles, Sanath sought greener pastures again—this time in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

“I had to pay 900,000 rupees ($3,000) to secure a driving job here,” Sanath (45), a father of two, told EconomyNext while having a cup of tea and a parotta for dinner near Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi.

Working for a reputed taxi company in the UAE, Sanath’s modest meal cost only 3 UAE dirhams (243 Sri Lankan rupees). Despite a monthly salary of around 3,000 dirhams, he limits his spending to save as much as possible.

Sanath has been in Abu Dhabi for 13 months but had to wait six months before driving a taxi and receiving no salary.

TOUGH REALITIES

“I had to get my UAE driving license. I failed the first trial, and the company paid 6,500 dirhams on my behalf, agreeing to deduct 500 dirhams monthly from my salary,” he explained.

“So far, I have repaid only 3,000 dirhams.”

To raise the 900,000 rupees for the job, Sanath borrowed money from friends and pawned jewelry.

“I don’t know if I was cheated by the agent, but I must repay that money and also send money for my family’s expenses,” he said, glancing at a photograph of his family in a Colombo suburb.

Working night shifts in busy Abu Dhabi, Sanath said, “If I can secure 9,000 dirhams monthly through taxi driving, I will earn 3,000 dirhams in the month after deductions for the license fee and any traffic fines.”

Sanath came to Abu Dhabi with seven other Sri Lankan men through an employment agency in the Northwestern town of Kurunegala.

“Only two of us have withstood the tough traffic rules and payment deductions for offenses,” he said. Some of his colleagues are still job-hunting, while others have returned to Sri Lanka.

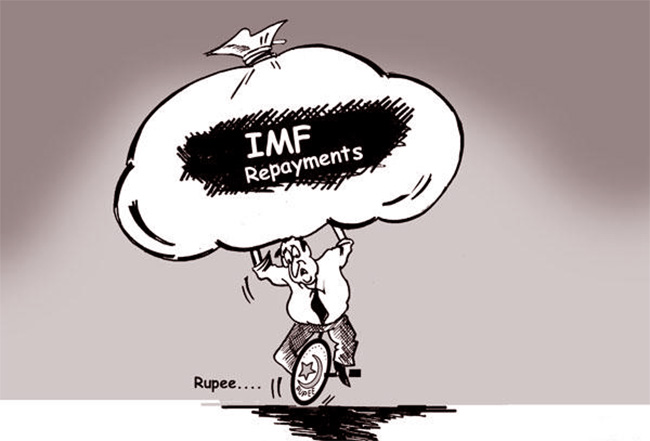

Sanath is one of around 700,000 Sri Lankans who have left the island in the last two years due to the economic crisis that forced the country to adopt difficult fiscal and monetary policies, including higher taxes and costly borrowing, exacerbating the cost of living.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE EARNERS

From January 2022 to the end of March 2024, at least 683,118 Sri Lankans migrated for foreign employment through legal channels, according to the Sri Lanka Foreign Employment Bureau.

They have sent $11.31 billion in remittances through official banking channels during the same period, central bank data shows.

Many Sri Lankans leave on visit visas, hoping to find jobs later, often guided by friends already working abroad. The economic crisis has pushed them to seek better opportunities abroad, despite the risks.

Sri Lankan authorities struggle to stop such risk-takers, who sometimes resort to illegal migration, despite warnings about human trafficking.

In Myanmar, 56 Sri Lankans caught in an IT job scam were detained earlier this year, and the government is still repatriating them.

At least 16 retired Sri Lankan military personnel have been killed in the Russia-Ukraine war after being misled by unscrupulous recruiters. Officials estimate that over 400 retired military officers may have left for similar reasons.

DISPERATE TO LEAVE

In March, Foreign Minister Ali Sabry warned against visiting any nation on open visas, urging Sri Lankans to emigrate only through registered agencies.

Despite the risks, many Sri Lankans are desperate to leave.

Abu Salim, a 32-year-old former rugby player, came to Dubai on a visit visa hoping for a banking job, which he never got.

Now freelancing in an insurance firm, he said, “I survive, and my relatives don’t see my struggle. It’s stressful, but still better than Sri Lanka right now.”

Suneth, a former top garment merchandiser, is also job-hunting in Sharjah after quitting his initial job in Sharjah.

“My worry is the visa. I must find a new job before it expires,” he said.

Many Sri Lankans in the UAE work multiple jobs, compromising their sleep and health to make ends meet. (Abu Dhabi/May 24/2024)