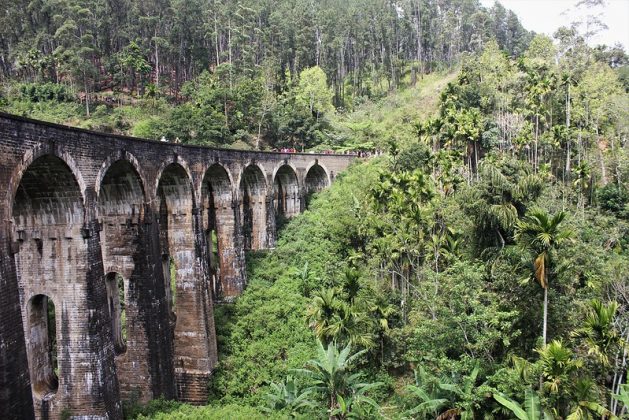

Local environmental experts stress that conservation is crucial to sustain the ecological services provided by forests in Sri Lanka. Courtesy: CC by 2.0/charlieontravel.com

By Devana Senanayake and Janik Sittampalam.

COLOMBO , Dec 15 2020 (IPS) – The Sri Lankan government recently cancelled three circulars that protected 700,000 hectares of forests, labelled Other State Forests (OSFs), which are not classified as protected areas but account for five percent of the island nation’s remaining 16.5 percent of forest cover.

Sri Lanka’s OSFs are areas managed by the Department of Forest Conservation (DFC), but are not a part of areas such as National Parks, Wildlife Reserves or Elephant Sanctuaries.

With the removal of three circulars, particularly 05/2001, control over OSFs have been handed back to Sri Lanka’s local authorities: District and Divisional Secretariats.

Indigenous Peoples & Local Communities Offer Best Hope for Our Planetary Emergency

Even before the removal of the circulars, land had been allocated to families to construct temporary buildings. The removal of the circulars legitimised this practice and expedited the process.

Local newspapers have reported that the removal of the three circulars was pushed by corporate interests under the facade of protection for smallholder farmers. While the veracity of these claims are unclear, deforestation has occurred at rapid rates in Sri Lanka over the last 54 years.

Convenor for the Center for Environment and Nature Studies, Dr Ravindra Kariyawasam, estimated that in 1882, Sri Lanka had a forest density of 82 percent but this reduced to 16.5 percent by 2019.

Like other developing nations such as Brazil, India and Indonesia, deforestation for a variety of development purposes has been pursued at the cost of the country’s natural resources.

But local environmental experts stress that conservation is crucial to sustain the ecological services provided by forests. As a result, some have called for sustainable mechanisms that consider conservation and agricultural production should be adopted in the bid to develop the country.

Unpacking the obstacles to conservation in Sri Lanka

Conservation has been complicated in Sri Lanka. One of the primary obstacles to the implementation of a successful conservation strategy has been the lack of coordination by the DFC and the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC), according to executive director of Center for Environmental Justice (CEJ) Hemantha Withanage.

Recently, there have been reports of land grabbing in Nilgala Forest in Sri Lanka’s Uva and Eastern provinces. While Nilgala Forest’s Eastern section of 9,000 ha is under the DWC, another 15,000 ha are under the DFC. As forest areas are allocated to separate departments, it is unclear how issues such as land management and land acquisition are managed.

While Sri Lanka has several environmental conservation laws such as National Environmental Act No. 47 of 1980 and the National Environmental Act of 1988, conservation is rarely favoured over human interests.

For example, in October 2017, Forest Department officers arrested 17 persons who attempted to cultivate land in the Radalla Forest Reserve in Sri Lanka’s Eastern province. The Pottuvil Magistrate issued an order for the continuance of cultivation until the case’s conclusion. The order blocked the DFC, agriculture department, DWC and the police from taking action against people cultivating on protected land. Moreover, the order threatened legal action against any officer who interrupted cultivation activities. This order alone resulted in the deforestation of almost some 200 acres of the reserve.

There are also limited personnel to parole the areas. Recent reports of deforestation from Ampara, in Sri Lanka’s Eastern province revealed that only 22 Forest Officers were available to protect the Pottuvil and Lahugala areas.

“They also do not have enough staff members in the field. One Forest Officer might have 17,000 to 18,000 ha of forest area so you cannot manage such a forest area with one person,” Withanage, executive director of CEJ, told IPS.

Forests have ecological services

Despite the challenges of conservation, deeply forested areas in the dry zone have endemic biodiversity (such as the Sri Lankan leopard, sloth bear and elephants) and ecological services that are far too important to fully compromise.

“A study done by the World Bank looked at the value of the ecosystems on the planet and estimated it to be valued at $24 trillion annually,” systems ecologist and founder of Analog Forestry, Dr. Ranil Senanayake, told IPS.

Sri Lanka has a series of cloud forests—a unique alpine forest type that absorbs moisture for the air. Water is captured and released continuously by the trees in OSF forests. Many major rivers such as the Mahaweli River and Welawe River are fed by this water release, particularly in the dry season. Limited soil erosion prevents desertification and nutrient cycling reduces the farmers’ dependence on artificial fertilisers.

Trees reduce air pollution and improve air quality in urban areas. A study by the Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering revealed that green zones in urban areas decreased the lead percentage by 85 percent. Moreover, carbon sequestration absorbed CO2 from the atmosphere and reduced the risk of climate change.

These services are invaluable and perhaps even more expensive to retain or replicate artificially. A study by K. Ninan and M. Inoue analysed the total value of Japan’s Oku Aizu Forest Ecosystem Reserve calculated ecosystem services such as: Water Conservation (valued at $1,385,430), Water Purification (valued at $46,725) and Air Pollutant Absorption (valued at $27, 039).

Can conservation and development be balanced?

There should be an evaluation of forests so that land can be released for development but the ecological services can be retained and the natural equilibrium of the environment is still kept intact, according to Senanayake.

Senanayake proposed a national system to evaluate the units released for development: “Certain pieces of land have limited ecological, biodiversity and biomass value. Those are the first lands that the government can think of giving out. Then there are lands of extreme value and therefore, these lands cannot be alienated. You may have the same endangered ecosystem in a local area. These ten pieces might be the only pieces in the entire planet. That’s the danger!”

When forests are released another solution is to provide incentives for conservation so that a proportion of the benefits of these ‘services’ can be reaped.

In Costa Rica, landholders are compensated for conservation of forests through tax certificates and direct payments. Pago de Servicios Ambientales (PSAs) are provided in different amounts for reforestation, forest management and natural regeneration.

Funding for these payments came from various sources such as fossil fuel tax and international donations, or by selling carbon credit bonds. By 1997, $14 million was paid for environmental services. These payments supported the reforestation of 6,500 ha, the management of 10,000 ha of natural forests and the protection of another 79,000 ha of forest.

A study by Conservation Biology in Costa Rica confirmed that agricultural areas with abundant tree cover provided services such as natural pest management, carbon sequestration and soil conservation.

According to Senanayake, perhaps the best scenario for local developers is to pursue methods such as analog forestry—an ecosystem restoration practice which considers forest formation and forest services to set up a system characterised by a high biodiversity to biomass ratio.

Senanayake implemented the practice on an abandoned rubber farm in Sri Lanka as an alternative to monoculture plantations. It has spread to several countries such as India, Costa Rica and Kenya.

“Analog forestry encourages you to mature your farm ecosystem which gives you stability and sustainability,” said Senanayake. “None of our agriculture considers our native biodiversity. Analog forestry demands that you also attend to that.”

“It pushes optimal production as opposed to maximum production. Maximum production pushes you to monocultures and depending on the market vagaries of one crop. Analog forestry helps you spread the risk. If the market for one thing decreases, there is a market for something else. So it’s optimal production.”

Senanayake currently plans to set up a state recognised course on analog forestry with the Vocational Training Institute of Forestry. With this minimum qualification he hopes that local people can then provide for themselves while still conserving their environment.