A Degree Of Complaisance And Inclusivity Will Go A Long Way

Comrade Rohana Wijeweera, the founder of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), was arrested and subsequently murdered 36 years ago on November 13. His disappearance in 1989 symbolised the turbulent end of the JVP’s second insurrection, extreme political violence involving the State, its affiliated groups, and the JVP itself. This offers us the chance to reflect on the past and the important lessons that can be learned, which will be crucial for Sri Lanka’s future.

1989: A Watershed Year

The late 1980s were one of the most painful chapters in Sri Lanka’s post-independence history. The 1983 anti-Tamil riots and the 1987 Indo–Lanka Peace Accord turned the political tensions that existed into open conflict. The Accord, introduced as a peace initiative, instead triggered widespread mistrust, and heightened nationalism in the South. The JVP, operating underground as it was already proscribed, seized on these sentiments to launch its armed campaign against the State.

Both sides responded with escalating violence. Thousands of civilians, activists, and ordinary youth paid with their lives. Forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings were tragically commonplace.

The year 1989 also coincided with major global shifts. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union signified the decline of the socialist order, which had inspired many leftist movements around the world, including those in Sri Lanka. Neoliberal economic policies were rapidly expanding, reshaping international relations and national priorities.

Three and a Half Decades Later: A Changed Political Landscape

Today, Sri Lanka stands in a dramatically different political momentum. The JVP, which struggled through parliamentary democracy, has travelled a long path into mainstream politics. The National People’s Power (NPP) coalition led by the JVP achieved resounding victories in 2024, forming the government under President Anura Kumara Dissanayake.

The NPP administration has committed itself to combating corruption, controlling narcotics trafficking, and rebuilding the credibility of public institutions. Like other global movements for reform, such as the progressive shift symbolised by Zohran Mamdani’s recent mayoral win in New York, the NPP government emerged from widespread public demand for change following years of economic decline and mismanagement by previous regimes. However, gaining political power is only the first step. Transforming governance and rebuilding trust will require a sustained commitment to transparency, accountability, and social justice.

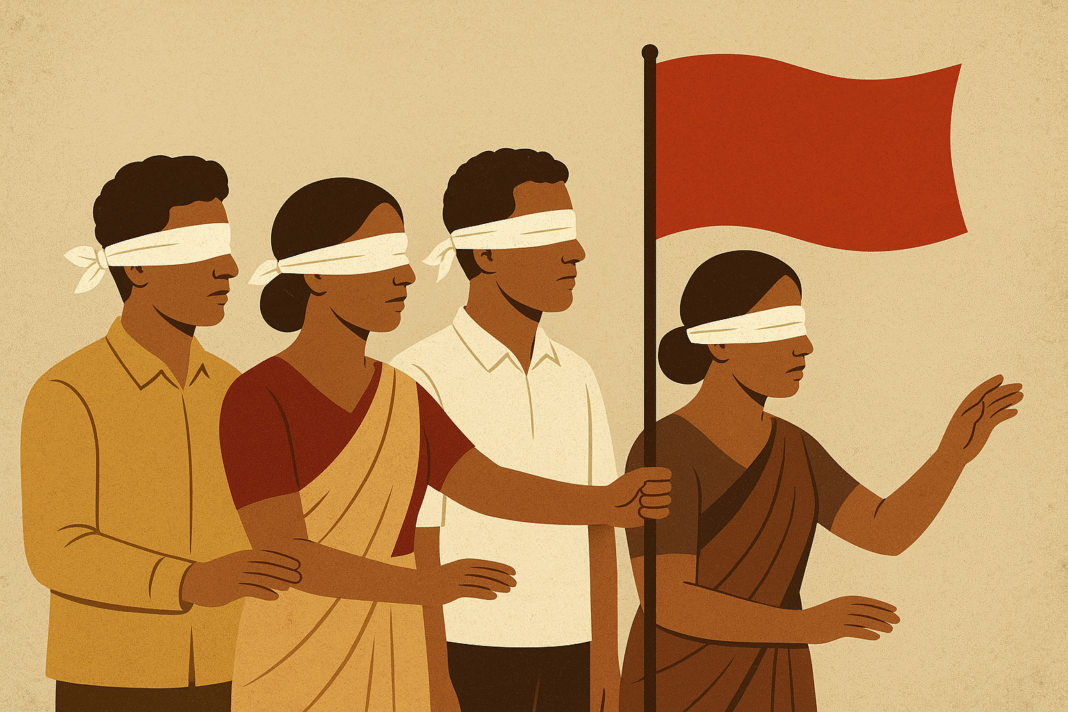

Blind Loyalty, Class Compromise, and the Social Justice Imperative

Sri Lankan politics has long struggled with the tension between blind loyalty to party, ethnicity, or faith, compromise with entrenched interests, and the quest for justice for all citizens.

Blind loyalty distorts democratic decision-making. It leaves little room for dissent or rational debate. During the Southern insurrections and the Northern conflict, loyalty to leadership, rather than to truth or humanity, justified violence and silenced differing voices. Such total and uncritical allegiance continues to threaten our institutions and civic values.

Globally, many countries struggle to separate religion from governance. With constitutional preferences granted to the majority faith, Sri Lanka—a multiethnic, multireligious society— faces the same challenge. Effective democracy requires that national policy be guided by equal citizenship, not sectarian influence.

Class compromise refers to alliances formed between leftist groups and capitalist factions. In Sri Lanka, partnerships between socialist parties and the SLFP date back to the 1950s. While such arrangements achieved short-term reforms, they also diluted transformative agendas. The global rise of neoliberalism from the 1970s further tilted power towards capital, normalising privatisation and diminishing labour rights.

Against this backdrop, social justice seeks to remove structural barriers and guarantee equal opportunities, particularly for marginalised communities. It calls for redistributing power as well as resources — a principle increasingly central to contemporary political reform.

Learning from the Violent Past

The violent episodes of the late 1980s continue to be the most contested part of JVP history. Allegations against government death squads and armed JVP units remain unresolved, contributing to deep emotional trauma among families that had become targets of the violence.

To their credit, in 2014, the JVP publicly acknowledged its role in the conflict and expressed regret for the suffering caused (https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c206l7pz5v1o). This was an important moral step toward national reconciliation. When the JVP returned to democratic politics in the 1990s, it was perceived as a sign of its readiness to participate in institutional procedures and nonviolent discourse.

Electoral success followed — especially in the 2004 parliamentary polls, where the JVP entered government as part of the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA). This participation provided governance experience yet also raised internal debates about ideological consistency and coalition politics.

Economic Challenges and Public Expectations

Following the 2022 Aragalaya protests, public confidence in political elites plummeted. The eventual ascent of the NPP reflected broad frustration with corruption and economic instability. Inheriting a fragile economy, the new government must now balance fiscal constraints while protecting vulnerable communities.

Despite early criticism, the administration has worked within the IMF programme to achieve stabilisation, while also signalling greater safeguards for social welfare. The 2025 budget introduced measures aimed at supporting low-income families, promoting local industry, and restoring economic growth.

Success, however, will rely on visible results, particularly in reducing poverty, supporting small and medium enterprises, and strengthening agricultural and employment opportunities.

Towards Wider Inclusivity

The NPP’s electoral coalition brought together youth, workers, and professionals from diverse regional and ethnic backgrounds. It demonstrated that politics in Sri Lanka can transcend traditional divides.

Yet, much more must be done. The concerns of Tamil and Muslim communities, including language rights, land issues, and political representation, remain unresolved. A firm and fair commitment to meaningful devolution is essential.

Sri Lanka’s dependence on a majoritarian model of governance has increased mistrust and fueled decades of conflict. In contrast, global examples show alternative approaches. For instance, Belgium has achieved equality between its Dutch and French-speaking populations through a system of constitutional power-sharing. This power-sharing has strengthened national unity rather than undermining it.

The government’s recent commitment to allocating funds for Provincial Council elections is a positive signal. A clear roadmap for fully implementing the 13th Amendment would reaffirm Sri Lanka’s commitment to pluralism and reconciliation and reap the benefits of participatory democracy for our multi-ethnic land.

Responsible Governance: Evidence Over Emotion

The central message from the upheavals of our recent past is simple: democracy cannot rely on blind loyalty. Effective governance must be built on:

- Informed public trust

- Respect for facts and law

- Accountability for wrongdoing

- Openness to criticism

- Civic participation at all levels

Both Sri Lanka and the United States illustrate how political gains achieved through wide grassroots mobilisation must be continuously nurtured. The NPP came to power on a wave of public activism. Maintaining that engagement, especially among young citizens, will determine whether reform succeeds or stalls.

At the same time, legal and institutional reforms must be seen to deliver justice. While anti-corruption and anti-narcotics measures are underway, delays in holding offenders accountable may erode trust. People need to see that the law applies equally to all.

And above all, governance must remain focused on easing the daily burdens of citizens: cost of living pressures, unemployment, healthcare, and education. Economic stability and social dignity must progress hand in hand.

Conclusion: A Future Built on Critical Thought

As we remember the harrowing events of November 1989, we are reminded that political violence and blind allegiance brought only divisions and tragedies. The responsibility of this generation, and its elected representatives, is to ensure such mistakes are never repeated.

Sri Lanka’s path forward hence requires:

- Critical thinking over unquestioning obedience

- Democratic debate over emotional polarisation

- Integrity over expediency

- Unity in diversity over majoritarian dominance

From the beginning, many JVP members and supporters believed that following orders without questioning was the only way to realise their goals. Nevertheless, that obedience can be attributed to the blind loyalty that unconditionally supported the unprincipled deviations from a left perspective, which ultimately led to devastating consequences.

A lack of democratic debate allowed the formation of groups within the JVP and caused the party to split more than once. Factions appear to have been unwilling to reach a consensus when their political perspectives were not always congruent. But throughout its existence, the JVP had, for the most part, reached decisions through unanimity.

Given that they have been elected to power, the NPP must take these issues more seriously. To prevent emotional polarisation, which will ultimately weaken or paralyse it as a political entity, democratic debate should be permitted, and critical thinking should be encouraged in the development of its policies to arrive at programmatic positions.

The JVP’s transformation into a governing force serves as an illustration that societies can progress beyond their conflicts. The challenge now is to create a political culture where trust is earned through transparent actions and not demanded through loyalty.

If Sri Lanka can develop an inclusive and mature democracy that respects all of its citizens and honestly learns from its past, those painful memories will serve the noble purpose of guiding us toward a just and peaceful tomorrow.

21 November 2025