Trials-at-Bar serve a salutary purpose, but within stringently circumscribed limits

There has been no previous instance of the procedure of a Trial-at- Bar being invoked against a former Head of State

The crucial attribute of the Attorney-General’s functions in this area is that he acts in a quasi-judicial capacity

The Supreme Court of our country has shown no inhibition in directly addressing the question whether the Attorney-General has properly exercised his discretion in laying the information which served as the basis of a Trial-at-Bar

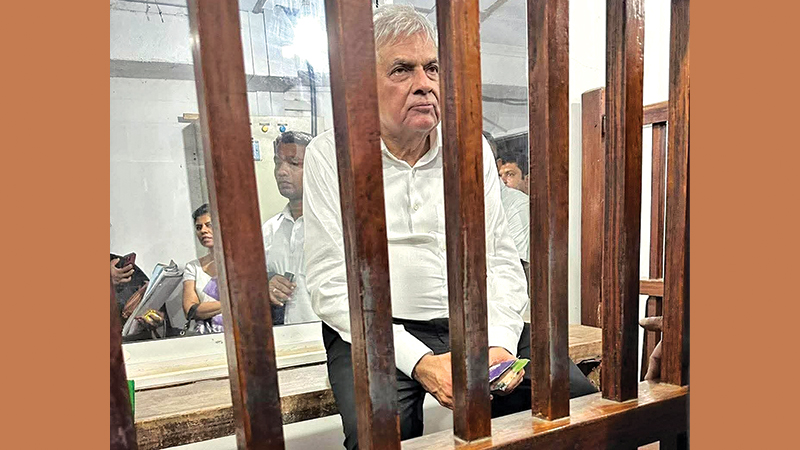

It is reported that a Trial-at-Bar is being contemplated in respect of allegations against former President Ranil Wickremesinghe regarding misuse of state resources for a visit to a British university on his return from attending sessions of the United Nations in New York and an official visit to Cuba. If this is correct, it would make legal history in our country, because there has been no previous instance of the procedure of a Trial-at- Bar being invoked against a former Head of State.

In view of the constitutional importance of the issues involved, the attempt is opportune to consider the conceptual and statutory foundations of our law relating to Trials-at-Bar, the boundaries of its application in practice, and the nature of the responsibilities attributed to the principal functionaries with regard to the conduct of these proceedings.

I. The Statutory Framework

A Trial-at-Bar is an extraordinary procedure operating over and above proceedings in regular courts exercising criminal jurisdiction at first instance. Its form is that of three judges of the High Court, sitting usually without a jury, to try an indictable offence. The main provision is contained in Section 12 of the Judicature Act, No. 2 of 1978: “Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this Act or any other written law, a Trial-at-Bar shall be held by the High Court in accordance with law for offences punishable under the Penal Code and other laws”.

The law of Sri Lanka makes provision for Trials-at-Bar in two different contexts.

(a) Mandatory

The trial of any person for the gravest offences against the State, constituted by Sections 114, 115, and 116 of the Penal Code, must in all circumstances be held before the High Court at Bar by three judges without a jury, despite any other law. This is the effect of Section 450 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, Act No. 15 of 1979.

The gist of offences to which this provision is applicable is conspiracy or preparation to overthrow, by unlawful means, the Government of Sri Lanka. This provision was applied in the case of 24 persons alleged to have attempted a coup d’état against the Government of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, a year after its election in July 1960 (R v. Liyanage).

(b) Discretionary

Outside this category, where recourse to a Trial-at-Bar is compulsory, there are other situations in which, as a matter of discretion, the Chief Justice may order use of this procedure. This course of action may be resorted to “in the interest of justice and based on the nature or circumstances of the offence”.

Trials-at-Bar, which may proceed either on indictment or on an information exhibited by the Attorney-General, are required to be held as speedily as possible, and generally in the manner of a High Court trial without a jury.

The power of appointment of High Court judges conducting a Trial-at-Bar is specifically vested in the Chief Justice. The Court, once appointed, has full authority regarding summoning, custody, and bail, subject to the restriction that bail may usually be granted only with the consent of the Attorney-General.

II. Appropriate Parameters

A useful point of departure, as a means of determining the proper limits of this judicial procedure, is to examine the character of offences which have led in our country throughout the post-Independence era to the constitution of Trials-at-Bar. A classification of the decided cases during this entire span of more than seven decades is attempted here for this purpose.

(1) Murder

Several Trials-at-Bar in Sri Lanka have been concerned with charges of murder, not per se, but invariably combined with circumstances which impart to the offence the added element of exceptional public importance, in terms of grave jeopardy to established institutions, public tranquillity, or seminal values underpinning governance.

The following are examples:

(a) The murder of a High Court judge engaged in the trial of five persons accused of capital offences pertaining to trafficking in drugs (Sarath Ambepitiya);

(b) The murder of a Member of Parliament in the midst of mob violence on a street, in the throes of widespread protests aimed at bringing down the incumbent government (Amarakeerthi Athukorala);

(c) The killing of two youth while in police custody (the Angulana case);

(d) The killing of villagers by army personnel during a public demonstration (the Rathupaswala case);

(e) The disappearance of a social activist and human rights defender (Prageeth Ekneligoda).

(2) Offences involving State security and possible contravention of International law charges pertaining to firearms and ammunition and their use on the high seas (the Avant Garde case).

(3) Alleged gross dereliction of duty by senior government officials, including a former Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and a former Inspector-General of Police, leading to the death of a large number of persons by explosions in public places such as churches and hotels (Easter Sunday Bombing case).

(4)Grave corruption allegations in respect of procurement or other major misdemeanours

- two Trials-at-Bar were appointed to hear cases arising from the Central Bank bond scam in 2016, alleged to involve a former Minister of Finance, a former Governor of the Central Bank, his son-in-law and others (Central Bank bond case);

- charges against a previous Minister of Health, senior officials of the Ministry, and others in connection with the procurement of substandard immunoglobulin vials, leading to deaths and grievous bodily harm (Keheliya Rambukwella);

- charges filed by the Financial Crimes Investigation Division against the Chief of Staff of a former President and a former Chairman of the Sri Lanka Insurance Corporation for alleged large-scale misappropriation of public funds (Gamini Senerath, Priyadasa Kudabalage).

(5) Sedition involving communal overtones and potential disturbance of the public peace (S.J.V. Chelvanayakam and others).

(6) Allegations relating to extra-judicial executions the trial of a previous Army Commander for statements made by him regarding unlawful execution of surrendering LTTE cadres (Sarath Fonseka White Flag case).

(7) Criminal defamation in volatile contexts

In 1954, in the earliest of this series of cases, allegedly defamatory remarks were published by the defendant in a newspaper known as Trine. The gist of the allegations was that Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, who had just relinquished the position of Minister of Finance to accept appointment as Governor-General, had engaged in “swindles on an international scale” (R v. Thejawathie Gunawardena).

The heinous character of the offences alleged, and the scope of their potential ramifications in all these settings, are evident at a glance. The distinguishing feature is not merely the gravity of the offence, but imputation of a wider dimension to it, typically in the form of a serious affront to the public wellbeing.

In the Thejawathie Gunawardena case, for instance, where the propriety of recourse to a Trial-at-Bar was vigorously challenged, the Supreme Court held that there was no ground for complaint because of the predominant element of public mischief apparent from the circumstances. This was due to the inflammatory content of the statements published, which could foreseeably “disturb or endanger the government” by igniting public feeling. Gravity of the allegations, from this point of view, and their probable impact on public confidence in the integrity of basic institutions of governance, were the factors relied upon to take the case out of the regular category of defamation litigation and justify use of the Trial-at-Bar procedure.

This characteristic of a high threshold of public importance, accompanied by complexity and volatility of the surrounding circumstances, is the central thread which runs through the diverse situations in which Trials-at-Bar have been constituted in Sri Lanka.

III. The Roles of Pivotal Functionaries

The principal responsibility is that of the Chief Justice and the Attorney-General. The essential nexus between their statutory functions is a salient feature of the law.

(i) The Chief Justice

In Somaratna Rajapaksa v. Attorney-General, it was clearly recognized that the repository of power to constitute a Trial-at-Bar is the Chief Justice, but subject to the requirement that an indictment or information “furnished by the Attorney-General” operates as the material basis for exercise of the Chief Justice’s authority in this regard.

An explicit trajectory is established, linking the initiative by the Attorney-General with the Chief Justice’s decision.

(ii) The Attorney-General

Action by the Attorney-General is located within the overall ambit of prosecutorial discretion vested in him in respect of a wide range of matters, including assessment of the sufficiency and probative value of evidence to warrant institution of criminal proceedings, the decision to indict, and withdrawal of a prosecution by means of the entering of a nolle prosequi. The recommendation in respect of a Trial-at-Bar falls into place within the field of this broad authority.

The crucial attribute of the Attorney-General’s functions in this area is that he acts in a quasi-judicial capacity. A basic anomaly in the role of the Attorney-General in our constitutional system is that he combines, in his office, a variety of functions and responsibilities which entail some degree of conflict with one another. Despite this lack of institutional coherence and consistency, what is beyond doubt in the present condition of the law is that, throughout the whole gamut of prosecutorial decision making, the Attorney-General is required to eschew all political and other extraneous considerations and to arrive at his decisions in a spirit of total objectivity.

This is one of the cornerstones of our system of criminal justice. Although there is a statutory choice or discretion built into the Attorney-General’s responsibility, H.N.G. Fernando C.J. has aptly commented: “Our law has conferred on the Attorney-General powers which have been commonly described as quasi-judicial and traditionally formed an integral part of the system of criminal procedure” (Attorney-General v. Don Sirisena). In similar vein, the Supreme Court, in Victor Ivan v. Sarath N. Silva, Attorney-General, observed: “The Attorney-General’s power is a discretionary power similar to other powers vested in public functionaries, held in trust for the public, and not absolute or unfettered”.

While the purview of prosecutorial discretion residing in the Attorney-General, by virtue of enacted law as well as inveterate tradition, is strikingly extensive, it is not an untrammeled power: it is not beyond the reach of the courts. In a trilogy of progressive decisions by the Court of Appeal, Sobitha Rajakaruna J., (prior to his elevation to the Supreme Court), asserted the principle that the Attorney-General’s decisions, in appropriate circumstances, are amenable to judicial review: Sandresh Ravi Karunanayake v. Attorney -General (CA/Writ/ 441/2021) ,Duminda Lanka Liyanage v. Attorney-General (CA/Writ/323/2022), Nadun Chinthaka Wickremaratne v. Attorney-General (CA/Writ/523/2024).

In Attorney-General v. Karunanayake, Samayawardhana J ( with the concurrence of Thurairaja and Janak de Silva JJ.) declared: “Politically motivated indictments following regime change pose a serious threat to the rule of law and public confidence in the office of the Attorney-General and the entire justice system. Judicial oversight plays a vital role in ensuring that prosecutorial discretion is exercised independently, fairly, and in compliance with the law”.

The Supreme Court of our country has shown no inhibition in directly addressing the question whether the Attorney-General has properly exercised his discretion in laying the information which served as the basis of a Trial-at-Bar.

In Thejawathie Gunawardena’s case, in proceedings before the Supreme Court, it was strenuously contended on the defendant’s behalf that the Attorney-General had acted ultra vires for a collateral or improper purpose. The submission was that the person allegedly defamed was no longer holding public office, and invocation of the extraordinary procedure associated with a Trial-at-Bar was, therefore, unjustifiable. The Supreme Court, sitting in appeal, having considered the issue in depth, rejected the submission on the ground that his tenure had been very recent, and that the proximity of his connection with the incumbent government gave rise to the likelihood of intensifying public feeling because of the volatility and range of the allegations made against him.

These trends of judicial opinion have the effect that the principle of justiciability of the Attorney-General’s initiative in this regard is firmly embedded in our law.

IV. Conclusion

Trials-at-Bar serve a salutary purpose, but within stringently circumscribed limits. The decided cases in our country, spanning more than 75 years, indicate with exemplary clarity the confines within which this extraordinary procedure has legitimacy. The essential consideration is that there should not be room for the slightest doubt that immaterial factors may have come into play in the exercise of discretion.

This far transcends the entitlement of individuals to due process and impinges upon the health and vitality of procedures central to the administration of justice. My teacher, Professor Sir William Wade, pre-eminent among exponents of administrative law in our time, who had the distinction of holding Chairs of Law successively in the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, told me that if he were asked to identify succinctly, in one sentence, the substance of the common law tradition, he would have no hesitation in replying that it consisted of robust hostility to unbridled discretion in public functionaries. Even the appearance of neglect of this rudimentary principle places in jeopardy the fulfilment of public aspirations about the quality of criminal justice.

(The writer is a former Minister of Justice, Constitutional Affairs and National Integration, Quondam Visiting Fellow of the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge and London and Former Vice-Chancellor and Emeritus Professor of Law of the University of Colombo)

Courtesy of the Daily Mirror.