Ending Rule of Men

Twelve years ago, ex-Foreign Secretary, H.M.G.S. Palihakkara, chairing the late H.L. de Silva memorial events in Colombo opined that what was prevailing in Sri Lanka was not the cherished Rule of Law but a system that could be branded as the Rule of Men in power.

What Palihakkara said was that the diminishing respect for the rule of law diminishes all of us as aspiring to create and live in a just society. He further elaborated his point as follows: “Such erosion will allow impunity to raise its ugly head. Usually, impunity signals the onset of decay. Neither those who govern nor those of us who are the governed will be spared. It impairs civilised life and democracy. And it undermines the investment climate. Conversely, the upholding of the Rule of Law manifestly strengthens sovereignty, pre-empts external calls for intrusive accountability, deters threats to the territorial integrity of the nation and facilitates the enjoyment of fruits of citizenship and democracy by all.”

Using rule of force

He warned that if Sri Lanka wants to create a good image about the country abroad, then it was essential for Sri Lanka to nurture a rich culture of the rule of law and not the widely practised rule of men at home. He concluded that “it is the duty of all to say yes to ‘force of rule’ (discipline made in a society by the introduction of a socially accepted set of rules) and no to ‘rule of force’ (administering a country by using coercive powers)”. Palihakkara’s wisdom was not heeded to by the Sri Lankan rulers at that time. The outcome was disastrous for the rulers: President Mahinda Rajapaksa lost power in 2015 and his brother President Gotabaya Rajapaksa had to abandon the power midway through due to a popular uprising by the people. It seems that the present Government is following these two leaders ardently believing that it could administer the country by resorting to the rule of force that entails the use of coercive powers to suppress freedoms of the people.

Worsening world ranking in Rule of Law Index

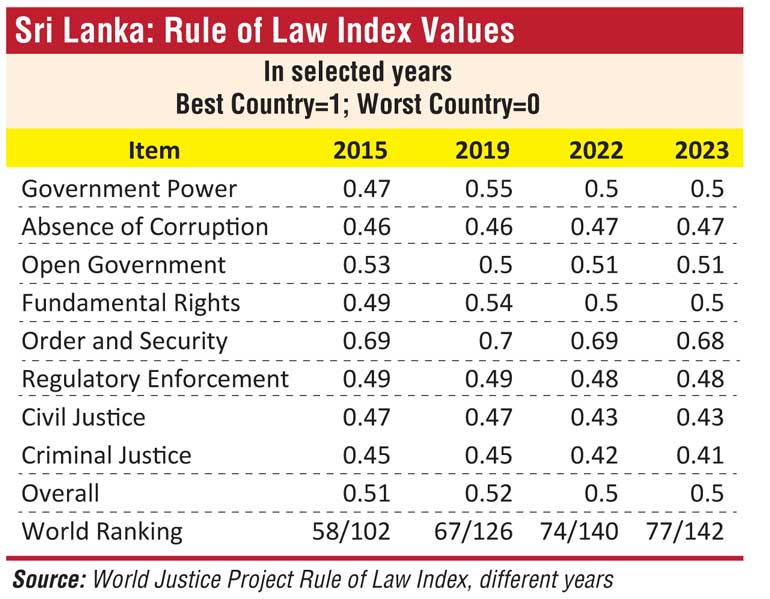

Sri Lanka’s track record of observing the rule of law has been pathetic as revealed by the global rule of law index compiled by the Washington DC based World Justice Project (available at: https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/global/2023/ranking). According to the index parameters, the best country can score 1 and the worst 0 as the overall score calculated by assessing eight different factors which are disaggregated into 44 subparts relating to the performance of the rule of law within a country. They are constraints on government power, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice, and criminal justice.

In all these respects, except one, Sri Lanka’s score has been 0.5 or lower. It has always been ranked at the mid-level and in 2023, it has lost three notches to be ranked at 77 compared to 74 in 2022. Table shows the values assigned to Sri Lanka by the World Justice Project in some selected years with respect to detailed factors that are included in the compilation of the index. All numbers are at mid level needing substantial improvement if the country desires to deliver justice to its people.

In all these respects, except one, Sri Lanka’s score has been 0.5 or lower. It has always been ranked at the mid-level and in 2023, it has lost three notches to be ranked at 77 compared to 74 in 2022. Table shows the values assigned to Sri Lanka by the World Justice Project in some selected years with respect to detailed factors that are included in the compilation of the index. All numbers are at mid level needing substantial improvement if the country desires to deliver justice to its people.

Eight important factors

The World Justice Project has clarified the meaning of the eight factors that have been used for compiling its index (available at: https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/factors/2022).

Constraints on Government

The constraints on government powers measure the extent to which those who govern the country are bound by law. It comprises both constitutional and institutional means by which politicians, their supporters, and officials are constrained in the exercise of their powers and held accountable under the law. It also includes non-governmental checks on the government’s power, such as free and independent press. Sri Lanka’s mid-level score on this factor indicates that its Government does not listen to the public opinion when administering the country. Hence, people have a very low control over the Government.

Three types of corruption

The factor, the absence of corruption, considers three forms of corruption namely, bribery, improper influence by public or private interests, and misappropriation of public funds or other resources. The index covers those in the executive branch, the judiciary, the military, police, and the legislature. Throughout, Sri Lanka’s score on this count has been below the mid-level indicating its action to eradicate all forms of corruption has been in vain.

Open Government

The third factor on open government measures the openness of government defined by the extent to which a government shares information, empowers people with tools to hold the government accountable, and fosters citizen participation in public policy deliberations. This factor measures whether basic laws and information on legal rights are publicised and evaluates the quality of information published by the government.

Fundamental rights

Fundamental rights

The factor on fundamental rights recognises that a system of positive law that fails to respect core human rights established under international law is at best “rule by law,” and does not deserve to be called a rule of law system. Since there are many other indices that address human rights, and because it would be impossible for the Rule of Law Index to assess adherence to the full range of rights, this factor focuses on a relatively modest menu of rights that are firmly established under the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and are most closely related to rule of law concerns. Sri Lanka should not have difficulty in adhering to these principles since it is a signatory to them as a member of the UN and has incorporated them to the constitution of the Republic.

Property rights

The security of persons and property is measured by the factor concerning order and security. Economists call this the protection of property rights which is fundamental to the operation of any economy. It is therefore, a precondition for the realisation of the rights and freedoms that the rule of law seeks to promote. Sri Lanka’s score for this is a little better than other scores since it lies between 0.6 and 0.7, a little close to some of the better performing countries.

Applying regulations

The fairness and effectiveness of the enforcement of regulations are measured by the factor on regulatory enforcement. Regulations, both legal and administrative, structure behaviours within and outside of the government. This factor does not assess which activities a government chooses to regulate, nor does it consider how much regulation of a particular activity is appropriate. Rather, it examines how regulations are implemented and enforced. Sri Lanka’s track record on this count has been unsatisfactory as revealed by the index sub scores compiled by the World Justice Project. Evidence shows that Sri Lanka has been using regulations selectively favouring those in the Government and penalising those who are opposed to it.

Civil justice

The factor measuring the standards of civil justice examines whether ordinary people can resolve their grievances peacefully and effectively through the civil justice system. It measures whether civil justice systems are accessible and affordable as well as free of discrimination, corruption, and improper influence by public officials. It examines whether court proceedings are conducted without unreasonable delays and whether decisions are enforced effectively. It also measures the accessibility, impartiality, and effectiveness of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

Criminal justice

Criminal justice

The efficacy of a country’s criminal justice system is looked at in the factor concerning the criminal justice. Such a system is a key aspect of the rule of law, as it constitutes the conventional mechanism to redress grievances and bring action against individuals for offenses against society. An assessment of the delivery of criminal justice should take into consideration the entire system, including the police, lawyers, prosecutors, judges, and prison officers.

Importance of observing rule of law

The mid-level score of Sri Lanka on all these counts means that, despite its bold pronouncements in international fora and during election times, indicates that the country should end its system of the rule of men immediately, as Palihakkara has warned 12 years ago. It should recognise the value of the rule of law for sustained economic development since it is an essential factor for assuring the quality of development.

How does the Rule of Law support economic development? If a nation respects the Rule of Law, there is proper maintenance of law and order by that nation and that law and order will help it to protect property rights, the property owned by people both individually and collectively. The first category is called the private property rights and consists of both the material property owned by a person and his labour, physical as well as intellectual. The second is called the public property rights and consists of all properties held by the state on behalf of people. Thus, all state lands, common properties, state enterprises and movable and immovable state properties that generate a benefit to people belong to this category.

The state is required to protect these public properties on behalf of people and, when it uses them for public’s benefit, it must do so by following a code of principles that ensures their proper use. Allowing some people to abuse public property or running public enterprises at losses is equivalent to robbing such public resources. Hence, the protection of property rights – both private and public – is so central to economic development that it is called ‘bread and butter’ of any initiative made by a nation toward attaining prosperity.

Freedom of thought and freedom of expression

A country that does not observe the rule of law, and follows the rule of men, prevents people from exercising a fundamental right necessary for inventions and innovations, namely, freedom of thought and freedom of expression. Finally, this is concerned about human liberty. The 17th century English philosopher John Locke put it aptly when he said that ‘where there is no law, there is no freedom’. This has been amplified by Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson in their 2019 book The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty drawing our attention to an age-old problem now known as the Gilgamesh Problem.

Gilgamesh problem

Gilgamesh was the ruler of Uruk in ancient Sumaria in the 3rd millenium BCE. According to the epic recorded in clay tablets, he was a remarkable ruler with foresight and wisdom. He is said to have created a city flourishing with commerce and provided excellent public services for the people living there. But like any ruler with absolute powers, he thought that the city as well as the people therein belonged to him. He enlisted the young males for his war campaigns and young girls for his carnal pleasures. When people could not bear with this tyranny anymore, they are said to have appealed to the heavenly God Anu for redress. Anu created a double of Gilgamesh called Enkidu and sent him to Uruk to fight with Gilgamesh and protect the people from the latter’s tyrannical acts. This was similar to the ‘checks and balances’ that we find in modern democratic constitutions.

Enkidu did his job well by checking Gilgamesh whenever he tried to exceed his authority. But after some time, Enkidu found that if he teamed with Gilgamesh, he could also benefit from those evil works. It was a ‘win-win situation’ for both and they willingly agreed to work together. Now people in Uruk had a new problem, tyranny by Gilgamesh and his corrupt double, Enkidu. This problem, known as the Gilgamesh problem, is a common issue faced by people at all times and in all societies. It is concerned with how to save oneself from the saviours.

Rule of fair law

People who follow the rule of men rather than the rule of law are potential Gilgameshes and Enkidus. Palihakkara warned us about this possibility 12 years ago. Today’s Sri Lanka provides ample evidence to prove that we have not learned a lesson out of it.

The low score given to Sri Lanka by the World Justice Project when it compiled the Rule of Law Index provides further proof of this unsavoury development. The wide factors which it has included in the compilation of the Index also tell us that it should not be mere ‘Rule of Law’ but ‘Rule of Fair Law’ indicating the necessity for considering the processes behind the observation of this vital principle.

In this connection, Brazil which is ranked at about the same level as Sri Lanka in the index has offered an example of how the rule of fair law could be violated by the authorities. In Brazil, there is a popular saying that “For friends, everything but for enemies, the law”. This preferential or discriminatory treatment of people depending on whether they are supporters or opponents should be avoided at all costs if the desire is to create a just society.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)