Image courtesy of CIVICUS.

(BY Sumudu Chamara/ The Morning.) During the past year (2022), Sri Lanka’s civic space has faced a multitude of serious challenges with protests being clamped down on, journalists being stifled, and protestors being targeted amidst public frustration with poor governance and the lack of accountability. In many cases, it was at the hands of the authorities including law enforcement and defence personnel. The oppressive and selective enforcement of laws, and also the introduction of laws that could be misused to oppress activists also remain a concern in Sri Lanka.

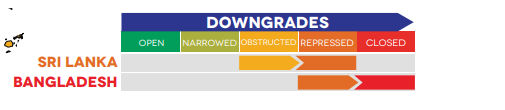

Conditions for the civil society continuing to worsen in the country has resulted in the country’s civic space rating being downgraded to “repressed” (from the “obstructed” status last year) by the CIVICUS Monitor, a tool that provides data on the state of the civil society and civic freedoms in 198 countries and territories. CIVICUS, a global alliance dedicated to strengthening citizen action and civil society, made these observations in a report issued yesterday (6) titled the “People Power Under Attack 2023”. Ratings of the countries range within “open”, “narrowed”, “obstructed”, “repressed” or “closed”.

The CIVICUS Monitor found that nearly a third of humanity, or 30.6% of the global population, live in “closed” societies, while just 2.1% of the people live in “open” countries, where the civic space is both free and protected.

Sri Lanka: A nation with ‘repressed’ civic freedom

Noting that the findings show a sharp decline in the civic space in Sri Lanka, the report explained that merely one year after mass protests ousted the previous Government, the new Government does not hesitate to use force to intimidate or disperse gatherings of people criticising the country’s rulers. The report highlighted: “In Sri Lanka, over the past year, the authorities have harassed human rights defenders, protest leaders and social media activists by hauling them up for interrogation or prosecution while others have faced surveillance, intimidation and threats. Journalists have been targeted with judicial harassment and restrictions for undertaking their work and assaulted during protests. There were reports of excessive force, including the use of tear gas, by the Police in response to several protests, particularly by students, as well as the intimidation of people from the Tamil minority seeking justice for past crimes in the Northern and Eastern Provinces and restrictions on their protests.”

With regard to the legal and regulatory situation pertaining to civic freedom, it explained that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Act is used to stifle expression, while the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act (PTA) is used to target and harass activists, journalists, protest leaders, and minorities. It expressed concerns that a revised version of the Anti-Terror Bill still puts rights at risk, while the Online Safety Bill could be used to further restrict online expression.

Regarding protests, the report added: “In Sri Lanka, the authorities repeatedly prevented journalists from covering demonstrations or accessing sensitive areas, sometimes with violence. Police and intelligence officials used summonses and lengthy interrogations to try to intimidate human rights defenders. The security forces violently broke up protests that called for everything from student scholarships to land reform to the release of people arrested in previous protests.”

“We are witnessing an unprecedented global crackdown on civic space. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka’s leaders have chosen to join this worldwide assault on citizens’ rights. If anything ties all attacks on civic freedoms together, it is that the Sri Lankan authorities do not want anyone to question their decisions. But, Sri Lankan citizens continue to mobilise to demand justice and reforms anyway. The Government should learn from the past and listen to the people exercising their rights, rather than trying to silence them through force,” the CIVICUS Monitor Lead Researcher Marianna Belalba Barreto said about Sri Lanka’s situation.

Civic space in Asia and the Pacific

By being downgraded, Sri Lanka has joined the group of “repressed” nations comprising Brunei, Cambodia, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. The “closed” category has grown this year (2023) from seven to eight countries. Afghanistan, China, Hong Kong, Laos, Myanmar, North Korea, and Vietnam remain in this category, while Bangladesh has now joined them as well. Five countries remain in the “obstructed” category. They are Bhutan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Maldives, and Nepal. Meanwhile, civic space in Japan, Mongolia and South Korea has been rated “narrowed” with Timor-Leste improving its rating to join this category, while Taiwan remains the only country rated “open”.

Describing civic space restrictions, the report said: “The main civic space violation documented in the Asia Pacific region is the use of intimidation to stop activists speaking out and journalists exposing violations. Another widespread trend across the region is censorship, used to block the criticism of those in power or to deny people the ability to receive and share information. Governments also detained protestors in numerous countries and prosecuted human rights defenders, using an array of restrictive laws.”

The use of intimidation as a tactic to silence human rights defenders and journalists has been documented in at least 22 countries in Asia and the Pacific, as per the report, which further said that among the methods deployed were the surveillance of activists and civil society groups, raids on the homes and offices of activists and journalists, and the vilification of and threats against their lives and safety.

Another key civic space concern in the Asia Pacific region is the use of censorship by governments, documented in at least 21 countries. The report said that over the year, the authorities used their powers to restrict access to information critical of the state by blocking television broadcasts and news portals, deleting social media posts, ordering the media to remove news coverage, banning publications and targeting journalists and news outlets. I

t was further pointed out that across the Asia Pacific region, people mobilised to call for democratic reforms, labour and environmental rights and to push for justice, equality and accountability, to which states responded by deploying security forces to arrest and detain protesters in at least 21 countries.

Another top violation documented across the Asia Pacific region was the prosecution of human rights defenders, reported in at least 13 countries. Many were criminalised under national security, public order or criminal defamation laws, as per the report.

Remedying the situation

To remedy the shrinking civic space, the report presented a number of recommendations for governments, the United Nations (UN) and international bodies, donors and the private sector.

These recommendations said that governments should take measures to foster a safe, respectful, and enabling environment in which civil society activists and journalists can operate freely without fear of harassment, intimidation, attacks, or reprisals, in line with international human rights commitments. Recommending that governments should work with the civil society to establish effective national protection mechanisms that respond to the needs of those at risk, the report added the importance of repealing any legislation that criminalises human rights defenders, protestors, journalists, and members of excluded groups.

Recommendations for governments further read: “Carry out independent, prompt, and impartial investigations into all cases of attacks on and the killing of human rights defenders and journalists, and ensure that those responsible are brought to justice to deter others from doing the same. Desist from using excessive force against peaceful protestors, stop pre-empting and preventing protests and adopt best practices on the freedom of peaceful assembly, ensuring that any restrictions on assemblies comply with international human rights standards. Review and, if necessary, update existing human rights training for the police and security forces, with the assistance of independent civil society organisations, to foster the consistent application of international human rights law and standards during protests, including the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials. Establish fully independent and effective investigations into the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers and agencies during protests and bring to justice those suspected of criminal responsibility.”

In addition, recommending that the reliable and unfettered access to the Internet be maintained and internet shutdowns that prevent people obtaining essential information be ceased, governments were further urged to repeal any legislation that criminalises expressions based on vague concepts such as “fake news” or disinformation, as such laws are not compatible with the requirements of proportionality. Publicly condemning defamatory remarks, threats, acts of intimidation and attacks on human rights defenders and excluded communities, is another recommendation.

Meanwhile, regarding the private sector, the report said that businesses should align their policies with international human rights standards, including the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, to ensure that any censorship request from governments is not enforced.

The recommendations urged donors also to take steps in this regard: “Provide long-term, unrestricted, and core support for civil society in countries where the civil society is facing increasing restrictions from states. Funders should provide specific support to groups conducting advocacy in countries with a rapidly closing civic space. Adopt participatory approaches to grant making. Include human rights organisations in designing schemes and conduct situation assessments with civic society organisations. Maintain engagement at every stage, including when funding has been granted, to create adaptation and reallocation strategies with grantees in response to difficult working environments. Prioritise security. In sensitive cases, donors need to balance transparency and security needs. Where civil society and human rights work is criminalised or human rights defenders are under surveillance or facing harassment, key information such as the identity, operations, activities and location of those receiving funds might need to remain undisclosed. Donors should support programmes to ensure that human rights defenders have appropriate training, skills and equipment to conduct their work safely.”

In addition, adapting grant making modalities to the emergence of social movements and youth activists, among other key elements of the civil society, was also recommended.

Courtesy of The Morning

Read full report here