Image: (c)Shehan Gunasekara/Daily FT

On 15 October, the Sri Lankan authorities imposed a curfew in parts of Katunayake Free Trade Zone (KFTZ) after hundreds of workers at the Brandix apparel factory in Minuwangoda tested positive for COVID-19. More than 1,500 people connected to the garment factory have been infected with COVID-19 since 9 October, and four factories, Chiefway Katunayake, Next Manufacturing, Naigai and Okaya Lanka, shut down.

Many KFTZ workers migrate from rural areas in Sri Lanka, and live in overcrowded boarding houses with minimum facilities. Some of these also accommodate pregnant women and mothers with their children.

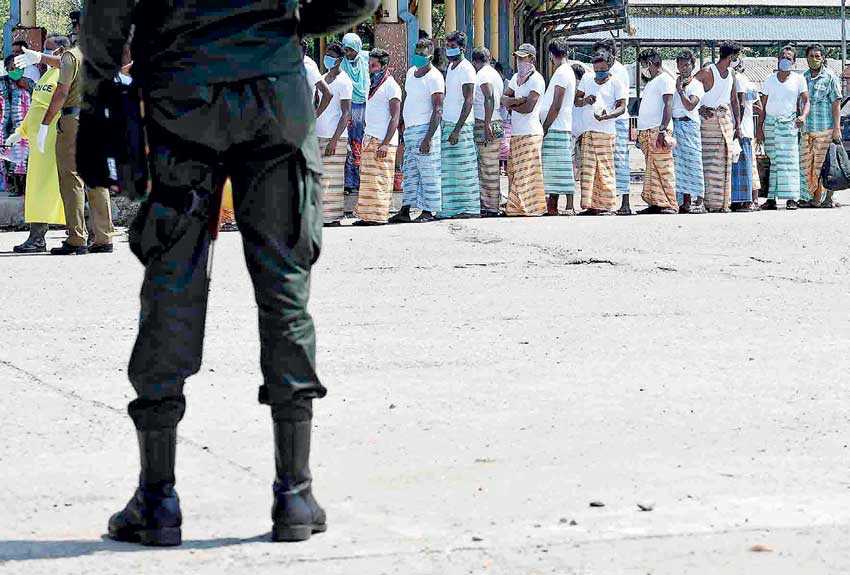

Military-led response subjects workers to greater threat and indignities

In an attempt to control the spread of COVID-19, the military was called in on 11 October to round-up workers, late at night and early in the morning, to forcibly take them to makeshift quarantine centres. According to the media and civil society reports, soldiers raided the workers’ boarding rooms, telling them they had five to 10 minutes to pack their bags. The workers boarded crowded buses and headed for quarantine centres, which were not established according to procedures established by law.

Trade unions and human rights activists spoke out that during this course of action by military, the workers were not informed where the centre was located nor provided with protective masks. They weren’t allowed to speak at all and children were separated from their mothers. When the workers arrived at the centre, they were given some food, which many workers found inedible.

The facility itself had not been cleaned, toilets were flooded and unsanitary, and no Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) tests had been conducted on any of the workers upon their admission to the centre. In short, the military-led response to the threat of infection ended up subjecting the workers to greater threat of contagion as well as numerous indignities.

Responses to pandemic must comply with human rights principles

A more sensible way forward is to ensure that responses to the pandemic comply with human rights principles, especially as we hear of more accounts of inappropriate or heavy-handed military behaviour in reaction to this public health crisis.

The manner in which the Sri Lankan Government and the military have handled the recent outbreak among the workers has been deeply troubling. The lack of clear information provided to the workers, unsafe transportation, unsanitary quarantine facilities established without a legal basis, and failing to conduct tests prior to loading workers onto buses and upon admission to the centre, and absence of judicial oversight is in clear violation of basic COVID-19 regulations adhered by the Government. At the heart of all these problems lies a heavily militarised and politicised COVID-19 response.

Heavily militarised and politicised COVID-19 response

In March, Sri Lanka’s first case of COVID-19 was reported. The Government set up the National Operation Centre for Prevention of COVID-19 Outbreak (NOCPCO) to prevent the spread of the disease.

However, instead of putting a medical professional or civil officer in charge of the Centre, the Rajapaksa Government picked Lieutenant General Shavendra Silva, an alleged war criminal, to head the NOCPCO. Silva was the commander of the 58th Division of the Sri Lankan Army, which was identified by multiple UN investigatory bodies as having been involved in the commission of serious crimes and human rights violations during the last stages of Sri Lanka’s decades-long armed conflict which ended in 2009.

President Rajapaksa has also appointed retired and currently serving military officials to other key public sector positions including the Secretary of the Ministry of Health, the Director General of the Disaster Management Centre, and the Director General of the Customs Department.

After delaying for several weeks, a countrywide curfew was suddenly declared on 20 March without adequate steps to supply essentials goods and medicines to the people. The President also gave full powers to the Police to arrest people for violating curfew.

Over 60,000 people have been arrested for alleged curfew violations and although most them had been released on bail, the Police stated that they will be prosecuted on the advice of the Attorney General’s Department when the normal Court proceedings begin once the COVID-19 epidemic is over.

The violators can be prosecuted in a Magistrate’s Court and if convicted, can be imprisoned up to six months and fined up to Rs. 2,000. Lawmakers argued about the curfew’s legality, but it continued to be enforced in several regions, as part of the State’s coronavirus containment strategy.

The military may have to conduct law enforcement functions during a state of emergency such as public health crisis. As the UN human rights guidance provided, the military may only be deployed in a law enforcement context for limited periods and specifically defined circumstances.

When the military conducts law enforcement functions, they should be subordinate to civilian authority and accountable under civilian law, and are subject to standards applied to law enforcement officials under international human rights law.

However, in Sri Lanka now, there is no public discussion or transparency about the actions and decisions of the military during the COVID-19 response. All decisions related to the public health crisis are being made by the NOCPCO with Silva at the helm, without any Judicial or Parliamentary oversight, nor any public institutional processes informing those decisions and holding him accountable to them.

Vulnerable ethnic and religious groups acutely affected

Vulnerable ethnic and religious groups are acutely affected by the militarisation of the public health response. Tamil organisations and politicians have continuously called for the demilitarisation of the north-east. Having the military to oversee the public health policy and to act as the State’s first responders also normalises military occupation, exacerbates the existing ethnic divides, and further deteriorates human rights in Sri Lanka.

Most of the quarantine facilities are located in the north and east of the country, which still remain occupied by the Sri Lankan military. Despite local concerns about locating quarantine centres in areas already subject to ethnic and political tensions, the Government ignored the local concerns and turned schools and educational establishments in the Northern and Eastern Provinces into the quarantine centres.

Furthermore, Muslims in Sri Lanka, have also complained about inappropriate State policies and violations of their freedom to worship. The Government-mandated compulsory cremations for Muslims who had died after contracting the virus goes against Islamic burial practices and World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines.

While certain limitations on human rights may be undertaken to confront the public health crisis, such limitations, in keeping with the Siracusa Principles, they must be for a specific public health purpose, established by law, non-discriminatory and necessary and proportionate to addressing public health.

Sri Lanka’s involvement of the military at every level, with limited parliamentary and civilian oversight, raises serious human rights and rule of law concerns. Public health officials have expressed disagreements with medical authorities in terms of statistics and strategy for managing the outbreak.

The Government will only be able to implement successful public health measures and maintain public support and confidence when its policies in response to the pandemic are evidence-based, human rights compliant, and transparent.

(The writer is Legal Advisor at the International Commission of Jurists, Asia & the Pacific Programme.)