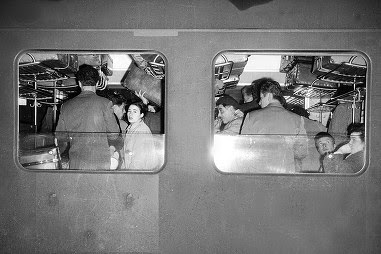

|

Migration is nothing new:workers

travelling between Switzerland

and Italy in the 1950s (RDB) |

Human rights/International

Scott Capper,

As Switzerland prepares to restrict the number of foreigners entering the country, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, François Crépeau, says we need to reconsider our understanding of migration. On February 9, a slim majority of Swiss voters accepted a proposal to introduce immigration quotas, effectively torpedoing a free movement accord with the European Union.

The initiative called for restrictions because its main backers, the rightwing Swiss People’s Party, said that too many foreigners were entering the country, putting a strain on a number of things such as public transport and the availability of housing, or abusing the unemployment and welfare systems. The party also believes it is in the interest of Switzerland to be able to manage immigration independently outside of foreign influence.

Crépeau argues however that limiting immigration will not make it go away. He believes that if migrants had a voice and could have an impact on politics, their needs and contributions would have far wider recognition and acceptance.

His main functions as special rapporteur include examining ways and means to overcome the obstacles existing to the full and effective protection of the human rights of migrants.

swissinfo.ch: Is it reasonable to consider restrictions such as quotas on migration?

François Crépeau : Migration has always existed and will always exist. It’s part of humankind’s DNA. It’s never actually stopped except by wars. Borders have always been porous and people have always found ways through them.

Discussions about quotas in Switzerland and other countries show that you have political parties that have an agenda on migration issues, but you also have the business community that has something to say as well as unions and international organisations.

These debates are necessary because societies have to assimilate that migration is a fact of life. It’s not the exception, it’s the norm.

But at present, migration policies are only discussed by citizens – about migrants, but never with migrants. That explains why the debate involving migration has moved on far slower than say women’s or gay and lesbian rights. These issues have moved faster on the political agenda because the people most interested [in their progression] have been able to participate, put forward their views and convince a large part of the population they were right.

Foreigner debate

In the past 20 years, discussions concerning foreigners in Switzerland have been largely fuelled by the rightwing Swiss People’s Party.

It has focused on asylum by calling for legislation to be tightened and on European integration by fighting any closer relationship between non-member Switzerland and the European Union.

Nevertheless, until the February vote, the People’s Party has been defeated in all its ballot box attempts to counter Switzerland’s bilateral and free movement of people agreements with the EU. The growing influx of EU workers was what prompted the party to launch its first initiative to cap foreign workers’ immigration.

The proposal fitted with the party’s policies over the past 20 years. However, during the 1970s, the party had actually criticised initiatives against “an excess of foreigners” as “unacceptable from the human and economic standpoint” and had rejoiced at their clear rejection at the ballot box.

swissinfo.ch: There seems to be a lot of anti-foreigner, anti-migrant feeling in the current political discourse. How do you explain why has become so prevalent if migration should be considered normal?

F.C.: Mainly because migrants don’t vote and don’t get elected, so their needs are not taken into account. Politicians don’t have any incentive to defend migrants and cannot be punished for it. And some politicians have been saying stupid things about migrants for 30 years without any pushback.

Jean-Marie Le Pen [founder of France’s rightwing Front National party] said 30 years ago “two million foreigners, two million unemployed”, meaning that if all migrants were forced to leave, there would be full employment for the French. It’s ludicrous in terms of the economy or social science, but if you ask most people on the street today, they still believe there is a correlation where there isn’t.

Politicians can get away with that because migrants aren’t talking. Most migrants believe the best strategy is to let go and move on. Don’t make a fuss, don’t get seen, don’t get heard. In most countries, migrants just disappear.

swissinfo.ch: Do migrants find it difficult to fight back too because migration is often framed with crime and illegality?

F.C.: Migration has been portrayed as an anomaly, as something that should not happen. Migrants have been portrayed as a threat from abroad. it’s the age-old fear of invaders. The language we use for migrants collectively is a liquid language.

We talk about flows and fluxes. We have to dam the flow, we have to prevent the invasion of migrants. If you talk about waves, flows or tsunamis of migrants, it’s like an indistinguishable mass with no individuals. It’s threatening because it’s a mass. Migrants are often portrayed as a group. People will say there are too many Muslims in the country, but Mohammed is a good guy.

The dichotomy between the mass and the individual is something against which women, gays and lesbians have worked. They’ve said that they are not a collective but all individuals. They don’t want to be told that as a group they cannot do something. Migrants are still portrayed as a group, taking jobs, increasing insecurity for example. This portrayal, these myths, these fantasies, aren’t countered because those most concerned by this debate don’t mobilise. And we as citizens don’t mobilise for migrants.

François Crépeau: A Canadian national, François Crépeau is a professor in public international law at the law faculty of McGill University in Montreal. In 2011, he was appointed United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada since 2012.

The focus of his current research includes migration control mechanisms, the rights of foreigners, the conceptualisation of security as it applies to migrants, and the rule of law in the face of globalisation.

Crépeau spoke to swissinfo.ch at the end of April on the sidelines of an event focusing on migrant rights organised by the World Trade Institute at the University of Bern.

swissinfo.ch: So what solutions are there to increase acceptance of migration? Better integration, faster citizenship?

F.C.: What is important is to listen to the migrants themselves. What do they want to do? Do they want to settle in a country, in which case we should provide them with the tools for settling in, which would be integration tools – making sure they speak the language properly, that they’re integrated in the labour market. If they are selected because their professional expertise corresponds to the needs of the country, we should provide them with some form of permanent residence that would lead to nationality quickly.

We also have to demystify the issue of nationality. What is nationality? For many people, being from a northern European country means being white and Christian, and this was the conception for quite a long time. This is changing and I think the younger generations have studied in schools that were multiethnic. They will not have the same idea of what it is to be Swiss or Swedish or Dutch or Danish that their grandparents had. This change in attitudes means that the idea of citizenship is evolving.

With the mobility of the workforce, globalisation, we recognise that multiple citizenship is an asset. These people are intermediaries between countries, between economies, business environments, cultural platforms and they can create wealth for both countries. So we should value multiple citizenship.

That means the public discourse by politicians about citizenship also has to change. You have rearguard combats about not trusting people with multiple citizenships, that people should not be allowed to choose a citizenship of convenience, as if a lot of people did that. It’s another myth on which populist movements are feeding.

swissinfo.ch: Does this mean citizenship should be separate from identity?

F.C.: Identity in the past 200 to 300 years has often been reduced to national identity and to a person belonging to a state. We have made national identity the supreme criteria for identifying people. But identity and citizenship are different aspects of our personalities.

Being French may be less important than being a mother for example. Many people leave their country because they marry someone from another and move abroad. It’s not that they don’t love their country of origin. It’s because another aspect of their personality is more important at that time of their life. So we have to demystify the idea that nationality is the ultimate allegiance.

Swissinfo