Cartoon by @awanthaartigala .

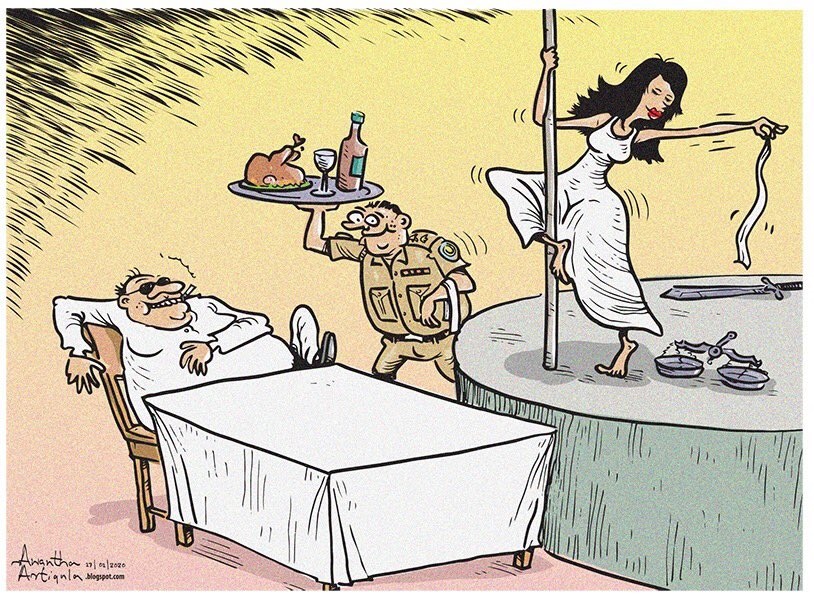

Leaked phone conversations between a politician and judicial officers with more details due to emerge has led to the interdiction of a Magistrate and inquiries into other judges even as the Sri Lankan public remain tantalised by these unfolding scandals. Weighty matters of governance are left discarded, the soaring cost of living is beside the point and planned constitutional convulsions that aim at returning Sri Lanka to dynastic power are not important. Instead this is the new Roman circus in town, with lions and their prey circling the arena to the shocked gasps of the plebians.

Alleging corruption in the judiciary

Even so and as the integrity of Sri Lanka’s judicial institution has come under horrified public scrutiny, the last thing that we need is increased use of contempt of court powers ostensibly wielded to ‘protect’ the adminstration of justice. There are some who have convincingly made the case that, if actor turned politician Ranjan Ramanayake, now more famous for his salacious phone conversations rather than anything else that he has done in his fairly commonplace life, wanted to establish the truth of a claim of corruption in the judiciary in regard to which he is being inquired into on contempt of court charges, he has gone a long way to establish his case as a result of this unholy fracas, regardless of the ethics of what he did. That may be one point of view. That is a matter that is already before court.

However, in the wake of this continuing scandal, to use contempt as a weapon to silence reasonable dissent expressed in regard to judicial orders, including a magisterial remand order, will only be counter-productive in the public arena. This is a country where far, far worse things have happened with little deterrent effect. Monks have stormed into courtrooms to insult judges and lawyers and have thereafter been pardoned by the executive. Military men turned lawyers (or vice-versa) have publicly maligned brave judges who have stood up to political pressure in controversial matters involving state abuses. These cases include the attempt on Rivira Editor Upali Tennakoon’s life (2008), the disappearance of journalist Prageeth Ekneligoda (2010), abduction and disappearance of 11 persons by the Navy (2008) and the abduction and torture of journalist Keith Noyahr (2008).

So when the Bar Association issues a sanctimonious statement as it did this week, pleading with lawyers to be ‘cautious’ when making statements in respect of judges and the judiciary, this is a forsaking of its essential responsibility to do more than just helplessly wriggle on the end of a stick. In this statement moreover, the Bar has expressed the marvelous sentiment that a few corrupt judges should not taint the entire institution. But it does not require the Bar to say this very obvious fact. What the Bar is called upon to do is to go a step further, beyond its uselessly rattling the cage in which it functions, and take concrete steps that address the issue of judicial integrity as well as judicial independence.

Mediating the relationship between citizens and judges

Foremost in this regard is the enactment of a Contempt of Court Act in line with Sri Lanka’s neighbouring countries which mediates the relationship of citizens with judges. A Code of Ethics for the judiciary is not likely to have any practical impact beyond affording a useful reason to have conferences and propound nonsense. However, a Contempt law has been a long felt need in this country. A decade or so ago, a draft Contempt law had already been approved by the Bar Council. Similar efforts were taken by the Law Commission of Sri Lanka, by the Editors Guild and by the Human Rights Commission.

The general contents of these drafts reflected modern contempt laws embodying best practices. Where the offence of scandalizing the court is concerned, there are competing interests in issue. These are the dignity and the authority of the judiciary on the one hand and the freedom of speech and the public interest in the due administration of justice on the other. The two extremes that Sri Lanka has seen so far (namely judicial coerciveness versus judicial silence) must yield to a sober balancing of these two interests. That balance should not be left to the individual discretion of a particular judge. Instead it must be provided for by law with appropriate penalties. Protection must be specified for fair and reasonable comment on cases. The rule against commenting on pending proceedings in court must be based on the modern test of substantial prejudice.

Courts in the United Kingdom have declared that there must not be gagging of bona fide public discussion of controversial matters of general public interes. Contemporaneous legal proceedings in which some particular instance of these controversial matters may be in issue are not automatically accepted as a ground to deny public discussion. Dealing with refusal to disclose sources of information and standards of professional ethics, courts are empowered to do so only when “disclosure is necessary in the interests of justice or national security or for the prevention of disorder or crime.” The greater the legitimate public interest in the information, the greater would be the importance of protecting the source.

Strategic measures needs to be taken to handle the scandal

The freedom to debate the conduct of public affairs by the judiciary does not however mean that personal criticism of judges or scurrilous and unwarranted attacks on the judicial institution, are condoned. These are also matters that are generally dealt with through a contempt law. In Sri Lanka, this becomes important in the context of unrestrained and vicious attacks on the judicial institution particularly in unregulated social media. Where Ramanayake’s leaked phone recordings are concerned, using contempt of court as a device to suppress discussion will be useless as the viral spreading of these recordings cannot be stopped by law.

Therefore, strategic measures are needed to be put into place in order that the credibility of the judicial institution in Sri Lanka does not suffer any more than it already has. One vital step would also be to make the functioning of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) proactively more transparent as it takes steps to discipline and control judicial officers. Rather than reacting to a scandal as is the case now, institutional accountability that does not impact negatively on the due administration of justice may be considered.

Sensible steps towards this end are needed, not flamboyant rhetoric or moralistic preaching from the Bar, which has no right to preach given its singular and long standing dereliction of duty in addressing outstanding issues of public concern in respect of the Bench and the Bar alike. Kowtowing to politicians, irrespective of whether these are green, blue or purple, is not one of those professional duties as much as this may be lucrative for lawyers to fill their deep pockets. Indeed this is one of the reasons why those trained in the practice of the law are looked upon with mistrust and suspicion by the public.

Dispelling that negative perception must be a primary aim in the future.

(Sunday Times)