by Shashik Dhanushka and Praveen Tilakaratne.

The silent protest against ‘Unethical Media Practice’ held on the 11th January 2019 by several civil society activists and artists opened up space for a larger discussion on the role of the media. This earned wider attention by the general public especially after the refusal of certain media channels to accept a letter handed over by a protester demanding truthful reporting, independence from political agendas and financial benefits, the upholding of ‘do no harm principles’, and accountability to the people. The media institutions, however, did not stop at merely refusing the letter handed over by the protestors, but went on to question the legitimacy of the protesters in questioning or challenging their work.

The post-protest discussion of the situation predominantly featured two positions. The first position was to maintain that the protest was a threat to the freedom of media and that it was rather a demand of a small portion of the society funded by foreign countries and guided by the UNP and the JVP. This view was mainly put forward by some of the media institutions themselves as well as certain politicians who held the same position. The second position was pitched against media institutions which were accused to be unethical and biased—particularly in light of the fact that they were not ethical enough to accept a letter handed over by means of a peaceful protest. This position was held by the parties who initiated the protest as well as people who subsequently came to appreciate their attempts in seeking unbiased and ethical media practices in the country. Our aim in this short article is to consider the possibility of using a different approach to understand what happened on the 11th of January as well as its aftermath. Here, it is important to understand the context which paves way for media institutions to gain such legitimacy to take decisions on behalf of people, to hold such strong positions and biases, and to respond so arrogantly and impudently to the critiques coming from people.

The role of media in recent past.

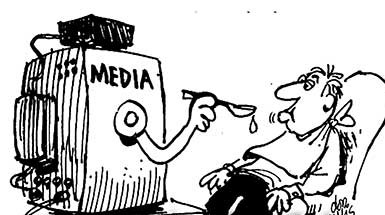

Although it would be naïve to assume that the media once used to function in a completely unbiased, apolitical fashion, it is also noteworthy that the function of media institutions in the last few years—especially the post war decade—has been changing significantly. Increasingly, the media seems to be engaging much more actively in opinion-making, passing judgments, deliberately obscuring and distorting certain facts and incidents, all the while being under the guise of objectivity and impartiality. The media, in other words, has increasingly become interested in acquiring a kind of political power and manifested a desire to intervene not only in the sphere of information or knowledge but also the will of the people. In light of these shifting intentions, roles and functions, it is prudent to ask if the media has, in certain ways, become an alternative to the state, a mediator to the state, or an informal or ad-hoc state. We would like to discuss these possibilities considering three practices of the present day media which closely mirror the practices of the state.

Delivery of justice

Almost all television channels and some radio channels feature segments where people can complain about various injustices they are facing. In itself, this is not a problem. However, the idea that media institutions can in fact deliver justice (and not just give coverage to injustices) is an instance of the media overstepping its traditional set of functions. We increasingly see that apart from reporting the complaints of the people, some media institutions engage in quasi-investigations so as to actually reveal the culprit. Due to the nature of such investigating and reporting, such media institutions take it upon themselves, either knowingly or unknowingly, not only to report information but also to judge, accuse and punish suspects. Of course, there are some instances where such practices have facilitated the delivering of greater justice, especially in cases where issues unaddressed and neglected by the state bureaucracy was given limelight. Thus our aim is not to pass a verdict on the role of the media but to question the circumstances that led the media to become a popular actor which can function as a substitute or complement to the state.

As researchers, when we go to the field, we often hear narratives which confirm the preference of the people to report their injustices to the media over the formal state mechanism. People often times believe that the media is more efficient in delivering justice than the state. They also believe that their injustices being discussed or reported by the media is in itself a kind of justice as well as a way of getting back at the wrongdoer or culprit. On the other hand, the media has greater leverage in representing certain injustices of the people since it can, without much barriers, address issues on moral grounds rather than on strictly legal ones. Additionally, people also believe that the media is helpful and much more efficient than the formal state mechanism when it comes to obtaining larger public attention as well as the attention of relevant authorities. The media is believed to contribute to the efficient delivery of justice even when justice cannot be expected from the formal mechanism of the state. In these instances with regard to the delivery of justice, it is therefore seen that the media contingently acts as an ad-hoc state, a mediator to the state or as a complement to the state.

Emergency relief

Emergency relief is also an area in which the media actively engages in the present day. Most media channels are very effective in providing emergency relief to the people who are affected by natural disasters such as floods and droughts. Although these programmes are sometimes criticized for promoting themselves as a brand in the process of collecting goods from the people and distributing them to affected communities, it is seen that during times of disaster a large number of donors as well as the affected communities themselves have greater faith in these relief programmes. Both the donors and the affected communities lack faith in the state mechanism due to allegations of corruption, ineffectiveness and inefficiency of state institutions when it comes to providing relief. Moreover, since media institutions appear more transparent than state mechanisms by actively broadcasting their relief programmes, they have been able to instil a kind of faith among large sections of society during times of emergency.

The role of the media in handling emergency relief is very similar to the way state functions. Whereas the state earns revenue by collecting taxes from the people so as to redistribute it to the areas where it is presumed to be needed, media institutions mirror this procedure when conducting emergency relief programmes. In the same way that the state assumes a kind of collective civic participation (in terms of taxation), in the context of relief programmes, the media also engages in a ‘by the people, for the people’ type of set up, where goods are collected collectively and distributed where needed.

Development Programmes

The implementation of development programmes is a particularly new trend in which the media is seen to directly encroach the borders of the state. The recent efforts of a certain electronic media channel to buy PET Scanner for the cancer hospital is a good example of this. During this initiative, too, the media channel collected money from the general public for this purpose. This too would typically be a task for the state funded by tax money. However, the inefficacy of the state has created a space for the media to intervene. Interestingly, a number of people are more willing to donate to these programmes rather than paying taxes to the government.

Another notable development initiative was carried out by one of the leading television channels which involved implementing 1,000 projects in the area of education, road development and water supply in several districts of the country. In numerous field sites, people from various strata refer to such programmes as the last and currently most desirable option for gaining access to services after failing to obtain services delivered by the state. These initiatives have also become desirable particularly since they help people bypass layers upon layers of politicised mediators between them and the state. The media is thus regarded as a more inclusive institution when compared to the state in the delivery of certain services.

An issue with Sri Lanka State?

In a recent study we carried out, which attempted to investigate the links between service delivery and state legitimacy, we were faced with a certain dilemma: the state as such was not some readily available entity or thing that could easily be thought about empirically. As a descriptive category, we found that the term itself was highly context dependent. However, in the case of Sri Lanka, a common feature that we could identify in many segments of society spread across various provinces was that there was a heightened presence of informal mediators and patronage networks. These mediators—for example, influential villagers who are faithful members of certain political parties, heads of development committees, etc.—are seen as neither within the state system, nor completely outside it. In any case, the boundaries of the state are extremely blurry, and the state—if it exists at all—is marked by jarring gaps and chasms. It is into these spaces that the media steps in so as to acquire greater power and hegemony. And in the context of the state increasingly failing to provide services to the people, the media is able to step in and pose as a more desirable contender to the position of the state. Since people too, as discussed above, prefer media institutions to the traditional state mechanism in several instances, media institutions are increasingly becoming hegemonic. What we saw on the 11th January 2019 is the adverse side of this phenomenon: where media institutions (much like the state) operate in the guise of ‘by the people for the people’, take power into their own hands and turn repressive. Effectively, the media has assumed for itself a particularly ideological role in declaring which segments of the population qualify as ‘citizens’ and ‘people’ and which segments don’t.

The writers are researchers attached to the Social Scientists’ Association. These views are their own.

-The Island