Janeen Fernando and Shamara Wettimuny.

Religious violence in Sri Lanka is widely considered a post-war phenomenon that emerged during the former Government’s tenure. Yet recent reports of over a dozen incidents of ethno-religious violence across the country in the past month directed at the Muslim community demonstrate that it is a continuing problem.

While anti-Muslim violence rose to prominence in the public consciousness in the aftermath of the Aluthgama riots, violence towards Sri Lanka’s Christian minorities is less known. A closer examination of past events reveals two disturbing features of religious violence in Sri Lanka towards Christians.

First, it is largely invisible and chronic; public attention is drawn to major events at the national level, but there is a lack of public awareness of everyday violence experienced at the local level. Second, violence against religious minorities is systemic. It occurs continuously across the country and involves State actors – regardless of the government in charge.

This article offers an insight into why this chronic and systemic problem has continued despite the governmental change of January 2015. It explains the role of State actors – particularly at the local level – in perpetuating religious violence through discriminatory practices and the protection of perpetrators.

The scale of chronic religious violence

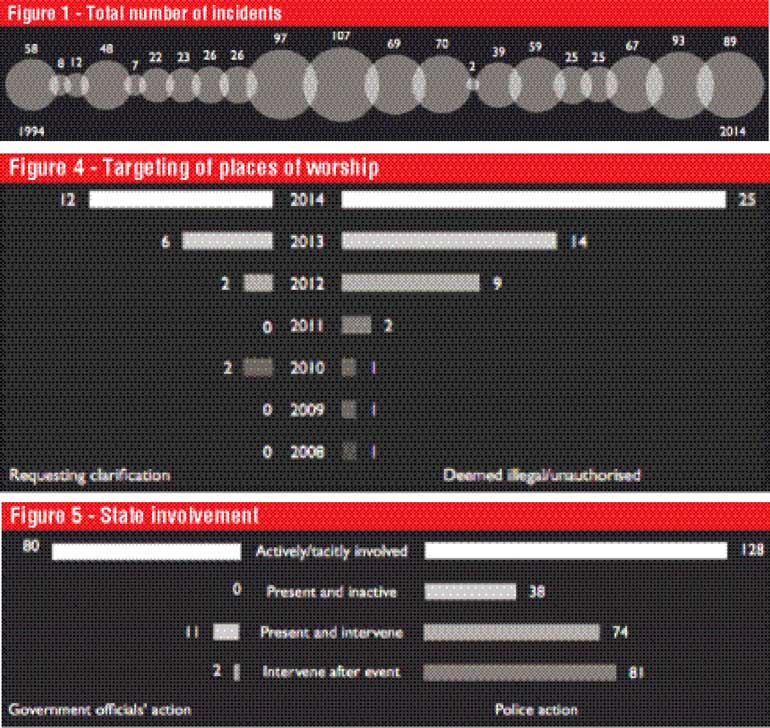

Verité Research recently studied and analysed a dataset on religious violence between 1994 and 2014 compiled by the National Christian Evangelical Association of Sri Lanka (NCEASL). The analysis revealed a clear pattern of ‘chronic’ religious violence. 972 reports of religious discrimination and violence against Christians were recorded during this period.1The figure suggests that for the past two decades, on average, an attack has taken place against a Christian person or group every week.

This trend has continued despite repeated governmental changes during this period. The governmental change in 2015 has likewise not resulted in any significant decrease in religious violence.

According to recent NCEASL reports, there have been 52 incidents of religious violence against Christians or Christian places of worship since January 2015.2 Although the incidence of physical violence is lower than previous years, threats, intimidation and ‘administrative restrictions’ have been used to target religious minorities.3

It must be noted that NCEASL’s statistics come from unofficial sources. However, Government data on religious violence has been consistently weak. For example, in February 2014, the former Government claimed that 95 out of 105 attacks deemed to be religiously motivated were merely local robberies.4

Verité’s analysis also reveals that political leaders or movements do not necessarily drive the persistent nature of chronic religious violence. They can drive an increase in violence (see 2013/2014 in Figure 1), but a significant level of religious violence persists regardless.5 This is because entrenched State structures often enable such violence. It also offers an explanation as to why the phenomenon has not ceased despite the change in government or rhetorical commitments at the national level to prosecute hate speech offenders.

Such commitments are in contrast with the State’s response to religious violence at the local level. This contrast merits a close examination of the role played by local State actors in perpetuating religious violence.

How the State enables violence

The State has enabled violence, defined broadly to include forms of structural violence such as discrimination, against religious minorities at two levels.

First, it has perpetuated discrimination. The NCEASL dataset suggests that significant institutional discrimination has taken place against religious minorities at the local level over the past two decades. A State institution or public servant was recorded as the key perpetrator of religious violence against Christians in 175 incidents (18% of all recorded incidents) between 1994 and 2014 (see Figure 2).6 This also appears to be a growing phenomenon, as 52% of these incidents occurred between 2012 and 2014.7 According to Minority Rights Group International, the State was a key perpetrator in 31% of incidents against Christians between November 2015 and September 2016.8

A significant majority (75%) of violence involving State actors against Christians during the past two decades included some form of discrimination by State institutions. These attacks include restrictions on the freedom of worship, the denial of entry to State schools on grounds of religious belief, and the refusal to act against perpetrators of religious violence. Furthermore, as demonstrated in Figure 3, State actors were, on occasion, reportedly involved in threatening Christians, and even in other acts of violence including physical violence and property damage.9

One of the key examples of State-sponsored discrimination of Christian minorities is the use of the 2008 Circular on the Construction of New Places of Worship. The Circular, which was issued by the then Ministry of Religious Affairs and Moral Upliftment, required the registration of ‘new places of worship’, and was used to shut down existing churches or worship services that had not registered with the authorities.

However, the Circular lacked any legal basis, as no law authorises the Ministry to regulate places of worship in such a manner. The widespread enforcement of the Circular illustrates the persistent nature of local State actors’ involvement in religious discrimination.

State-enabled discrimination against places of worship heightened in 2013 and 2014; 39 churches were shut down for failing to register (see Figure )4.10 Even though article 14(1)(e) of the Constitution guarantees the freedom of worship, the constitutionality of this Circular is yet to be successfully challenged. It continues to be enforced even after the change in government. Between November 2015 and September 2016, NCEASL reported 14 incidents against Christians that involved the use of the Circular.11

Second, the State has perpetuated religious violence by being tacitly involved in incidents or by failing to act against perpetrators. In fact, police inaction was widely reported between 1994 and 2014 – even when the police were physically present at incidents involving religious violence (see Figure 5).12 For example, the police were alleged to have passively looked on as mobs or individuals attacked Christian worshippers, pastors, or the physical premises of churches.

Under the current administration, State actors were noted as ‘intervening negatively’ in 60% of incidents against Christians.13 The inaction of or support towards perpetrators by law enforcement authorities help to create an environment of impunity that further enables religious violence.

Ending religious violence

Data from the past two decades suggests that religious violence is deeply rooted in Sri Lankan society due to its chronic and systemic nature, and the State’s role in enabling it. Therefore, the occurrence of religious violence is not necessarily dependent on a specific government in charge.

This article suggests that ending religious violence in Sri Lanka requires a serious transformation of State institutions, particularly at the local level. The first step in ending violence is therefore acknowledging the need for such transformation. The Government then needs to move beyond rhetorical commitments and take decisive measures to ensure that State actors, particularly at the local level, cease discrimination and carry out their duties of investigating and prosecution. Without such institutional change, Sri Lanka’s minorities will continue to face chronic and systemic religious violence.

(Janeen Fernando and Shamara Wettimuny initially conducted the research used in this insight for the report Silent Suppression: Restrictions on Religious Freedoms of Christians, 1994-2014 produced by Verité Research in partnership with the National Christian Evangelical Alliance of Sri Lanka.)

Footnotes

1Verité Research & NCEASL, Silent Suppression: Restrictions on Religious Freedoms of Christians, 1994-2014, (2015), at 6.

2See NCEASL, Attacks on Christians in Sri Lanka, at: https://slchurchattacks.crowdmap.com/reports/.

3Minority Rights Group International & NCEASL, Confronting Intolerance: Continued Violations Against Religious Minorities in Sri Lanka, (2016), at 10.

4Comments received from the Permanent Mission of Sri Lanka on the draft report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on promoting reconciliation and accountability in Sri Lanka (A/HRC/25/23) (February 2014), para.30.

5Verité Research & NCEASL (2015), at 17.

6 Ibid., at 18.

7The data used in this study was collated entirely by non-governmental organisations and religious groups. Verité Research has not independently verified the data.

8Minority Rights Group International & NCEASL (2016), at 12.

9Verité Research & NCEASL (2015), at 19.

10 Ibid.

11Minority Rights Group International & NCEASL (2016), at 14.

12Verité Research & NCEASL (2015), at 19.

13Minority Rights Group International & NCEASL (2016), at 12.