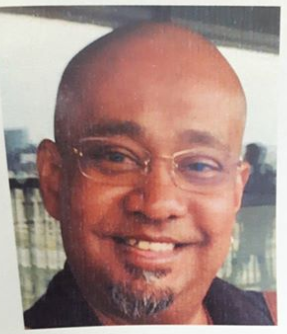

Image form Saroj Pathirana face book.

By Yolanda Foster.

Spring

I first met Prasanna in in the 1990s when I was a researcher at the Social Scientists Association (SSA) in Colombo. At that time he was working on a project about caste issues. I remember going to Summer Gardens one evening– a café where you could sip a Lion lager and chat over ‘bites’. We talked about the problems of a majoritarian state and the politics of amnesia surrounding the JVP insurgency and other dark periods of Sri Lankan history. We also talked about postcolonial writers like Fanon and failures of Empire worldwide. Our chats weren’t just about politics – Prasanna shared his early love of cinema with memories of seeing French new wave films at the Alliance Francaise down Barnes Place. His knowledge of world cinema was inspired, he said, by one of the Directors of SSA, Charlie Abeysekera.

In those days Sri Lanka was going through a period of possibility. President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga came to power in the mid-90s promising ‘Freedom from Fear’ and colleagues at SSA were working on challenging nationalism and racism. One of my earliest photos of Prasanna is outside the Fort Railway station where a group of us joined Women for Peace in an anti-racist vigil. Prasanna was sensitive to the issue of Tamil rights and joined initiatives exploring peace, constitutional reform and social justice.

I also remember his love of food and hospitality. When I moved into a new flat in Wellawatte he and another friend, Ranjith, performed an auspicious milk boiling ritual followed by some delicious Sri Lankan cooking.

Winter

The end of the war in Sri Lanka in 2009 was a nadir in Sri Lankan history accompanied by terrible human suffering. I sat with Prasanna one afternoon looking at photos of dead and maimed children sent from the Vanni region in northern Sri Lanka. He was interested in how these images could gain wider coverage given the clampdown on freedom of expression in Sri Lanka and supported a number of initiatives to bring attention to the terrible crimes committed. Many Sri Lankans did not want to believe that their state was capable of such horror and closed down. Prasanna helped to make a short video – a justice and accountability wall. This video was showed by Amnesty at a number of discussions – the images serving as undeniable facts when many Sri Lankans were prepared to believe the lies told by the Rajapaksa government rather than confront the brutal truth. Prasanna had himself experienced state terror and was someone I could talk to. He had known dark moons and lost half his classmates during the ‘80s insurgency. There were very few people I could ask to look through photos from the No Fire Zone which I found repulsive and horrifying. But Prasanna brought a professional visual eye to looking at the images and shared a story about how this was not the worst he had seen. After the tsunami in Sri Lanka he had to make a media trip to his hometown of Galle which was devastated by the tsunami. He recounted how he had to numb himself with Johnny Walker after he and a friend filed a report having seen hundreds of dead bodies in the mortuary. ‘But we wanted to tell the story’…he was always interested in stories.

Autumn

Prasanna embraced the seasons enjoying the spectacular colours of Autumn in the UK. I remember strolls through some of London’s Parks and fun faux Bollywood photos that he took of Sri Lankan friends. His embrace of changing seasons extended his interest in conflicts beyond Sri Lanka as he took on film work in Uganda and South Sudan. Prasanna also deepened his skill of video work helping on projects like Black Brittanica and making a documentary about Sivanandan (a Sri Lankan Trade Unionist). Through his relationship with Margaret he deepened his interest in race, class and identity. He deeply admired Margaret and her passion for art, politics and story-telling and in her house found himself at home.

His life in the UK allowed him to share a more relaxed side away from deeply politicised Sri Lanka. Prasanna could sometimes still you with a throwaway vignette like how he had been one of the last people to see Sivaram (a journalist abducted and killed) alive. He seemed to have lived many lives and had been through many personal and political struggles. Always busy, he was sometimes mysterious but I came to realise this was part of living life in the shadows of a state that cannot face its past and where sometimes to survive requires subterfuge.

Summer

One of Prasanna’s gifts was his appreciation of art and music and his desire to share this with others. He gave me a copy of Carlos Saura’s film Tango which swept me away in its innovative presentation of the magical city of Buenos Aires, its desires and rhythms. Despite Sri Lanka’s failure to produce a great political leader he valued its cultural maestros like Khemadasa and Dharmasiri Bandaranaike. One of his favourite places in London was the Tate Modern where he liked to meet friends for coffee and enjoy exhibitions. The last time we met he was vividly describing the 2016 Georgia O’ Keefe exhibition. One of the last projects we were involved in together was a poetry competition in Sri Lanka on the theme of disappearances. Prasanna pushed for a trilingual book which wasn’t without its challenges but returned him to his desire that all cultures should be valued and that Sri Lanka should rise above a parochial majoritarianism. His imagination was wider than his island home and I still remember the way his face lit up when he first walked down the Southbank on arrival in London and the world was once again alive with possibilities.