|

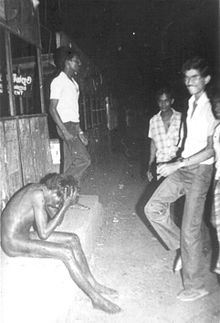

| A stripped naked Tamil youth sits on a concrete step at the Borella bus stand as a laughing Sinhalese mob dance around him. |

Dr.Wickrema Weerasooriya

In a ground breaking judgment – the first of its kind in Sri Lanka – which will especially interest proprietors and editors of newspapers, photographers and the media – a three judge bench of our Supreme Court recognized the “Economic Rights” of a newspaper journalist to nine exclusive photographs taken by him.

Several years later these photographs had been published in a newspaper without his consent, without his knowledge and without any acknowledgment. The journalist was awarded one million rupees in damages although the claim was for Rs.2.5 million.

The landmark judgment was delivered a few days ago on October 5, 2012, by Supreme Court Justice ShiraneeTillakawardane (with whom Justice Saleem Marsoof and Justice Hettige, both President’s Counsel, agreed).

The journalist who won the case was Shanta Chandragupta Amerasinghe. He had taken the nine photographs at Borella during the communal riots of July 1983 when he was working for the “Aththa” newspaper.

Chandragupta Amerasinghe sued the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd (ANCL) which had published the impugned nine photographs in the “Daily News” and “Dinamina” newspapers July 24, 1999, both papers being owned by ANCL. Neither the Daily News and the Dinamina had obtained Amerasinghe’s consent to publish the photographs. Far from obtaining his consent or approval, they had not even taken the trouble to inform him – before or after publication. Nor had they acknowledged that the photographs were his. Amerasinghe learnt of their publication when he saw them in the two papers.

Justice Tillakawardane delivered an excellent judgment. It is well reasoned and reinforced by a clear exposition of the relevant law. It also recognizes and strengthens the role of journalists and a responsible media. This article gives only a synopsis of the judgment which this writer is confident will soon appear in our law reports and law journals. The judgment sets out the facts leading to the dispute and the litigation, and the evidence led by both parties at the trial in the High Court. The following account is taken from the judgment.

It is common knowledge that communal riots had broken out in Colombo in July 1983. The plaintiff, Chandraguptha Amerasinghe was then a journalist/photographer at the “Aththa” newspaper. He took the nine photographs at Borella. It was indeed a volatile context in which he took the photographs. He endured great difficulty in taking them, including intimidation, threats of harm and actual assault. He was photographically capturing the unfolding events of the communal riots of 1983 in Colombo. So dangerous and unpredictable was the atmosphere of the riots that Amerasinghe would sometimes expose only a single frame on a roll before storing it for safekeeping. He was anxious to prevent the loss of precious footage due to the imminent danger of his camera being snatched and/or broken at any moment.

His simple narrative of the facts at the trial disclosed succinctly, the risk to life and limb that he willingly exposed himself. He did this probably recognizing his social responsibility and seeing himself as the conduit in supplying explicit and vivid information, which he discerned and recognized as being the need of the hour, for the people of a nation to make informed choices. However, due entirely to the promulgation under Emergency Regulations of the Gazette No. 245/8 dated 18th May 1983 of a ban on the publication of incendiary photographs (that could ferment communal instability) the journalist/photographer Chandraguptha Amerasinghe could not publish his photographs immediately.

When Amerasinghe took the photographs in July 1983, he was employed at the “Aththa” newspaper. By July 1997, he was working for the “Ravaya” newspaper. In connection with the 14thAnniversary of the 1983 Riots, the “Ravaya” published a Commemorative Supplement and in that some of the photographs that Amerasinghe took appeared. However, “Ravaya” newspaper had obtained Amerasinghe’s consent to print and publish his photographs in that Supplement.

Two years later, in July 1999, the Ravaya newspaper once again published the same photographs. Importantly, on this occasion on July 24, 1999, (to be exact) the Daily News and its sister paper Dinamina (both owned by ANCL) also published the photographs as parts of news articles on the 1983 Riots. However, neither the Daily News or the Dinamina had obtained Amerasinghe’s approval or consent – directly or indirectly – to publish those photographs. Also, both these newspapers omitted any citation listing Amerasinghe as the source of the photographs; nor did these two papers mention how the photographs were obtained.

Also, when sued by Amerasinghe as the plaintiff, the ANCL, as the defendant unequivocally conceded two important facts. First, that the photographs in question were taken by Amerasinghe during the July 1983 riots and secondly that the Daily News and the Dinamina published the photographs on the date and in the manner alleged by the plaintiff.

Although the Supreme Court judgment itself does not disclose the date on which the plaintiff Amerasinghe filed his action in the Commercial High Court of Colombo, this writer’s researches from examining the appeal brief shows that the action was filed July 23, 2001. At that time the law governing Intellectual Property in Sri Lanka on an issue as to the copyright of a photograph, was the Code of Intellectual Property Act No. 52 of 1979. This law was replaced by the Intellectual Property Act No. 36 of 2003 which governs the current law. There is no difference between the Code of 1979 and the Act of 2003 on the subject matter of this action.

Accordingly, the Commercial High Court Judge and the three Judge Supreme Court bench had to decide Amerasinghe’s complaint according to the provision of the Code of Intellectual Property of 1979. Simply stated, Amerasinghe’s case against the ANCL was as follows:

(i) As a journalist at Aththa, he took these nine photographs of the communal riots in Colombo in July 1983. The photographs were taken at Borella under extreme conditions including danger to his life.

(ii) The photographs could not be published at that time because of a ban on such publication by a Government Gazette notification which was produced in court.

(iii) Thereafter by July 1997 he was working at the Ravaya paper. The Ravaya published these photographs on two occasions with his approval.

(iv) However on July 24, 1999 two papers of the defendant ANCL – the Dinamina and Daily News published these photographs without his knowledge, approval or acknowledgement.

(v) By the above act, the ANCL violated his economic rights to the said photographs guaranteed by section 10 of the said Code of Intellectual Property and his moral rights guaranteed by section 11 of the same Code. Because of such violation he was entitled to Rs.2.5 million from the defendant ANCL (Ultimately he was awarded Rs. one million).

ANCLs main defences

to avoid liability

Having conceded that the photographs were taken by the plaintiff Amerasinghe and that two papers of ANCL published the photographs as alleged, ANCL took up two main defences to avoid liability and payment of any damages to Amerasinghe. Firstly it said that Amerasinghe had “tendered consent” to ANCL “to allow ANCL’s publication of the photographs”. Secondly, that Amerasinghe did not have the capacity to consent to the publication of the photographs by ANCL or put in another way Amerasinghe’s “employment arrangement” with the Aththa newspaper at the time he took the photographs did not permit Amerasinghe to retain ownership of the photographs.

At the appeal before the Supreme Court, Justice Tillakawardane rejected both these arguments of ANCL. Firstly, Her Ladyship said that these arguments encompasses the larger issue as to whether Amerasinghe is entitled to the Economic Rights arising from the copyright of the photographs in terms of the Intellectual Property Code referred to above. The answer to this question is “an issue of fact and not of law. If the Supreme Court as an appellate Court had to try that issue it would naturally require “the ascertainment of new facts”. Built into that first question is the second question whether Amerasinghe “had the capacity to consent” because at the time he took the photographs he had a contract of employment with the Aththa newspaper.

“Both these questions” observed Justice Tillakawardane” are not pure questions of law but are mixed questions of fact and law” and it is well settled that an Appellate Court like the Supreme Court cannot hear argument on issues which are based both on fact and law. Citing precedent, Justice Tillekawardane said, “A pure question of law can be raised in appeal for the first time but if it is a mixed question of fact and law it cannot be done”. Accordingly, the failure of the defendant ANCL during the trial before the Colombo High Court to (i) challenge the originally and ownership of the work or to (ii) lead any evidence during the course of the trial or at the time of cross-examination, are errors in litigation strategy that cannot be rectified through an appeal. Having said that, the Supreme Court is not obliged in this appeal by ANCL to consider matters which ANCL had failed to lead evidence at the trial.

However, Justice Tillakawardane perhaps due to the importance of this case for the cause of journalism and public interest of the media – went on to analyse “the Economic Rights issues to show that ANCLs actions in this matter were not “legitimate”. Her Ladyship then summed up the relevant copyright law as follows:-

1. Section 7(h) of the Code sets out a definition of the scope of work to be protected by copyright.

This section expressly includes photographic work.

2. Section 10(a) of the Code sets out the framework for the economic rights of the author and provides the author with exclusive rights to do or authorize reproduction.

3. Section 11(1) of the Code discusses the moral rights of an author and states that the author of a protected work shall have the right to claim authorship of his work in connection with acts referred in Section 10 and therefore reproduction of the said photographs under Section 10(a) is a violation of the author’s moral rights.

4. Section l3 (b) of the Code states that notwithstanding Section 10, protected work can be used without the author’s consent:

. . . in the case of any article published in newspapers or periodicals on current economic, political or religious topics . . . the reproduction of such article or such work in the press or the communication of it to the public, unless the said article when first published . . . was accompanied by an express condition prohibiting such use, and that the source of the work when used in the said manner is clearly indicated.

5. Section l7 (1) of the Code indicates that the rights protected under Section 10 are those of the

author who created the work.

6. Section l7(3) of the Code discusses works created in the course of employment indicating that where in the course of the author’s employment under a contract of service or work commissioned, the rights in Section 10 will be transferred to the employer or commissioner, where terms to the contrary are not stipulated.

Having set out the applicable law, Justice Tillakawardane next showed how the law did not help ANCL to defeat the plaintiff’s claim, Her Ladyship said:-

“From the above review of the rules governing copyright, it appears that the Appellant (ANCL’s) case rests solely on the application of Section 13(b)’s “newsworthiness” exemption or, alternatively, the availability of the allocation of presumed employer ownership under 17(3). Neither, rule, however, is applicable to the case at hand”.

“The Code’s Section 13(b)’s exemption is unavailable to ANCL for the simple reason that, at the time of ANCL’s publication of the photographs in 1999, the communal riots of 1983 were no longer current “political” events. While it could be argued that the 14th anniversary of the 1983 riots was itself the current event to which ANCL’s publication was connected, the legislative intent of 13(b), clearly was to allow for the dissemination of information surrounding actual transpired events, and not to serve as a loophole for use of material in subsequent “news cycles” of an initial event. This determination, combined with the fact that ANCL appears to have added insult to injury by failing to even acknowledge the source from which the said photographs were taken leads this Court to conclude that the High Court Judge was correct in finding that ANCL could not rely on Section 13(b) of the Code”.

In also rejecting ANCLs defence that the photographs belonged to the Aththa newspaper and not to its employee, (Amerasinghe), Justice Tillakawardane said:-

“The presumption established under Section 17(3) (of the Code) that an employer holds ownership in employee-created work is also unavailable to ANCL. The words crucial to our determination of the inapplicability of` Section 17(3) are; “in the absence of contractual provisions to the contrary”.

While it may well be that the Respondent’s (Amerasinghe’s) contractual relationship with “Aththa” newspapers — his employer at the time the photographs were taken – did not stipulate that Amerasinghe would retain ownership of them, ANCLs failure to introduce or request the introduction of the contract between Amerasinghe and “Aththa” newspapers into evidence for review, precluded the High Court from being able to determine whether Section l7(3)’s presumption was met.

Had the contract been presented an analysis of, among other things,

(i) whether the photographs were taken for personal interest or investigation

(ii) whether the photographs were taken during or outside of working hours

(iii) whether the photographs were taken in furtherance of Amerasinghe’s work assignment and professional objectives, may well have led the High Court to have concluded that ownership remained with “Aththa” newspapers and not Amerasinghe.

As the High Court was not afforded the opportunity to undertake such a factual analysis – and since such questions of fact cannot be reviewed at the appellate level, this Court finds that the Learned High Court judge did not err in holding that damages occurred to Amerasinghe on the basis that he had Economic rights in the photographs.

The evidence before the Court therefore leads the Court to conclude that the photographs were taken for personal interest or investigation and not in furtherance of a work assignment that Amerasinghe had, at the risk of personal safety and with his camera and film.

Therefore the photographic works are owned exclusively by Amerasinghe, who being the author is the first owner of the copyright in his photographs especially as the evidence is that he never transferred his ownership and he therefore continued to retain ownership”.

Perhaps again because of the importance of the issue before them and also its public interest, Justice Tillakawardane went on to examine the legal position under the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 1886 to which Sri Lanka is a signatory. Under the above Convention copyright for creative works do not have to be asserted or declared, as they are automatically in force at creation and are not subject to any “formalities” such as registration. As soon as the work is written or recorded on some physical medium, the author is automatically entitled to all copyrights in the work, as well as any derivative works. In addition, the Convention ensures that the right are protected until the author explicitly disclaims them or the copyright expires. Significantly, Justice Tillakawardane said:-

“Consistent with Section 17(3) of the Sri Lankan Code, which refers to photographs taken in the course of employment under a contract of service, the Berne Convention also deems that the photographer is the sole owner of the copyright in a work upon its creation, in so far as the image was not made under an agreement to the contrary, in which case the ownership of the copyright would vest in the employer”.

Having decided to uphold the judgment of the High Court in favour of the photographer, Justice Tillakawardane took the opportunity to suggest some reform of the law to ensure that authors of creative work (such as the journalist/photographer Amerasinghe) are fully protected. Her Ladyship drew attention to Continental European law and the United Kingdom law where the Economic Right of a creator are better protected and said:-

“Under the current system of law in Sri Lanka, the author is not encouraged to create works outside the ambit of the employment contract or terms of work commissioned out of fear of losing rights to the work. This disincentive, in the future, could lead to lack of journalistic motivation and therefore deterioration in investigatory reporting and subsequent communication to the public. The public has a right to information both communicated via articles, photographs and other medium. As a result of narrowly interpreted laws this right to information may be restricted and ultimately confine the media, which would ultimately impact the fabric of social justice that holds a nation together”.

“In this regard, the Court wishes to draw attention to the approach taken in continental European States where employers must purchase the usage rights from the author by means of an individual or collective agreement. The authors retain any usage rights not licensed to the employer by that contract, for example the right to reuse photographs already published would require permission from the original creator unless the right to reproduce is explicitly stated in the contract, the rights have expired or such reproduction is restricted by law. They are usually entitled to receive further remuneration for uses that go beyond those covered in the contract of employment. The law must at all times balance the exercise of an author’s copyright with public interest. This is seen clearly in the United Kingdom where Section 171(3) of the Copyrights Designs and Patents Act 1988 provides the courts with the jurisdiction to refrain from enforcing copyright claims on the grounds of public interest”.

Finally the Supreme Court justified and confirmed the award of Rs. one million as damages against the ANCL by the High Court. The judgment noted that photographs were taken during the communal Riots of 1983, a period of extreme unrest and conflict among ethnic communities in Sri Lanka. The photographs were not merely photographs of the aftermath of the riots but of actual live incidents that took place in the Borella area in real time. The photographs taken by Amerasinghe seem to be exclusive photographs which represent the appalling violence that took place during the riots and it is alleged that there are no other photographs by any other photographer depicting the scenes as seen in the photographs. Further, Amerasinghe had been subjected to assault, intimidation and threats and in fact his camera was destroyed during the course of taking the photographs. There was no dispute that the photographs were taken in difficult and dangerous circumstances and with grave danger to Amerasinghe’s life.

According to the evidence of Amerasinghe at the trial, one of the photographs had been sold at the value of Rs.10,000/- in 1996. Despite this being the only indication of value, the Supreme Court is in agreement with the view expressed in the English text by Cornish on Intellectual Property that the work of a humble photographer is in the same category as the work of a great artist. Thus, the Supreme Court was not willing to disturb the Learned High Court Judge’s assessment of the commercial value of the photographs. This Court agrees that the “exclusive, historical and invaluable nature of the photographs is independent of how often they were sold and how much they were sold for – the lack of an existing market does not alone suggest an absence of value”.

For the above reasons, the Supreme Court held that Amerasinghe – the journalist/photographer had possession of the Economic Rights to the said photographs and affirmed the judgment of the High Court and dismissed the ANCLs appeal. The Supreme Court also ordered the ANCL pay the damages awarded (Rs. one million) with the cost of appeal fixed at Rs.25,000/-. In a final observation at the end of the judgment, Justice, Shiranee Tillakawardane said, in words that merit verbatim quotation:-

“There is indeed an urgent need for protection of journalists like the Respondent (Amerasinghe) who with skill and commitment respond to the journalistic duty to honor the citizenry of our nation by fulfilling their primary obligation to report on facts in an unbiased, independent, undistorted, and disciplined manner, providing the unvarnished truth whilst maintaining an objective perspective of the people and events they cover. Their journalistic lens needs to be strengthened and empowered by law and their skills be developed through education and investment, propelling them in turn to report with a higher degree of accountability, independence and fairness. A nation of people who make their life’s choices on the information they receive from the media need to support and acknowledge their bravery and fearlessness especially when they become independent monitors of power and the checks and balances in exposing the truth, thereby being a cornerstone in creating a fair and just society.

The extended lens of dedicated, fearless and responsible journalists has oft been the tool in effecting social justice and they must be protected, nurtured and supported, as much as an irresponsible journalist who distorts and violates the truth for biased reasons must be soundly condemned and exposed as they shame a noble profession”.

Courtesy: The Sunday Island

Photo by Chandragupta Amerasinghe published in Wiki Pedia without nay acknwledgement