These are curious times indeed. Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa and his supporters who treated the Sri Lankan media and the legal system as their family hunting ground are struggling to emerge as newfound libertarians. We witness with enormous skepticism their ‘strutting and fretting’ on the political stage to protect the propriety of appointment to the Office of the Attorney General and (quite piquantly) to safeguard media freedoms.

Repression in its varied forms

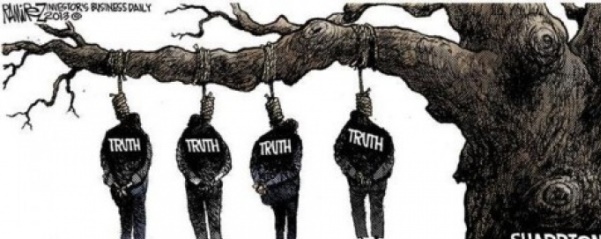

It was once a great game of the Rajapaksa regime to unleash its salivating media bloodhounds for the express purpose of savaging its critics. Quite apart from the editors and journalists killed, Rajapaksa propagandists attacked independent opinion to an unprecedented extent. This columnist has had first-hand experience of such calumny as a result of raising legitimate questions on Rule of Law failures.

If these questions had been addressed then, Sri Lanka would have been spared the supreme indignity of being lectured to on accountability by world powers who, to put it mildly, do not practise what they preach. The indignant reactions of United Kingdom ministers and British newspapers over the recent finding of a United Nations investigative body on the ‘arbitrary detention’ of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange are examples enough.

But returning closer home, even an incomparably degenerate Rajapaksa decade does not mean that media repression cannot be practised in other, subtler ways. Some of those Rajapaksa media bloodhounds are now accommodated within the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe government to practise old mischief but for a different paymaster. We await their amusing acrobatics.

The independent regulation of media

More worryingly, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s remarks this week that erring journalists of the private media would be dismissed and frequencies given to private broadcasting stations withdrawn ‘if they do not behave’ raise several concerns.

To be clear, the improvement of media ethics is no small matter. Political agendas, sexism, racism and at times, deplorable crudity (such as the needless controversy over the operatic rendition of ‘Danno Budunnge’) covertly characterize the manipulation of news and commentary. A professional industry response is seen to some extent in regard to the print media. But the electronic media has yet to initiate this discussion.

On its own part, the Government must heed the admirable warning issued by the Supreme Court almost two decades ago, that ‘the airwaves/frequencies are public property and a Government is only a trustee for the public’ (see Determination Re the Broadcasting Authority Bill, S.D. No 1/97 – 15/97, 5th May 1997). The Court threw out a Broadcasting Authority proposed by the Kumaratunga Presidency on the basis that it allowed for excessive political interference. The regulating and licensing of media is best left to an independent Authority. The sight of the Prime Minister threatening to take swift punitive action against journalists and withdraw frequencies of broadcasting stations is unnerving to say the least. This is antithetical to the very concept of ‘good governance’ which his Government so loudly if not hysterically espouses.

Failure to reach out to citizens

Overall, there is a particular trend becoming visible. As the inflammatory rhetoric of the Rajapaksa lobby gathers strength, its complaint of marginalization in Parliament resonates with force among some. The absence of an effective opposition on the floor of the House is a contributory factor. Corruption cases are only filed against Rajapaksa proponents while equally corrupt worthies in the Government are running free.

Meanwhile the Wickremesinghe-Sirisena coalition appears unable to reach out to ordinary people and clearly explain its difficulties not only in regard to economic woes but also the acutely sensitive question of war-time accountability. This recklessly courts a blow back from the citizenry, stoked by supporters of the former president, many of whom are fifth columnists secretively biding their time in government ranks while others perform as agent provocateurs.

For however much the government may say that the constitutional reform process is broad-based, the reality is quite the converse. It is much the same for the reconciliation process, driven largely from Colombo, operating within limited time frames and generally characterized by confusion worse confounded. Immediate measures in consonance with the Rule of Law such as the expeditious trial of detainees under anti-terror laws or release if held without charges are studiously bypassed. The Audit Bill and the (Cabinet approved) Right to Information Bill still await passage in Parliament. These laws will transform the functioning of government far more effectively than convoluted constitutional reforms.

A dangerous path to tread

These issues are only aggravated by Prime Ministerial tirades against journalists and also against Sri Lanka’s powerful medical lobby over the proposed Economic and Technology Cooperative Agreement (ECTA) with India. Opponents of ECTA argue that this will flood Sri Lanka’s service sector with Indian professionals. Quite apart from the substantive import of objections in regard to what essentially remains a framework for an agreement, the Government’s response leaves much to be desired.

The Prime Minister resorts to a familiar refrain that for every person who comes onto the streets to oppose the ECTA, he can bring out double that number. Surely this should not be the clarion call of an administration elected to power just last August? Should not documents in regard to such matters be readily available for public scrutiny and consultations held with professionals rather than reacting so provocatively?

Prime Minister Wickremesinghe’s annoyance appears to be driven by the fact that some journalists and doctors were ‘lackeys’ of the Rajapaksa regime. Yet similarly obnoxious media ‘lackeys’ are now part of this coalition administration. This begs the question as to whether it is not the ‘lackey’ tag per se but the opposition to government policies which is the rub. Other onetime ‘lackeys’ who have (presumably seeing the error of their ways) chosen to tag along with this dispensation are exempted from such tirades. Undoubtedly this is a dangerous path to tread for a Government flamboyantly elected on ‘good governance’ promises.

In the final result, absent significant course correction, the deterioration of confidence in Sri Lanka’s political leadership is inevitable. This will determine the country’s eventual electoral trajectory, notwithstanding glowing tributes from abroad. Before the 2015 Presidential poll, clear warning signals were ignored by the Rajapaksa regime to their downfall. It appears that this Government is equally and culpably blind to potential perils.

– Courtesy The Sunday Times