Chief Justice Mohan Peiris stopped further inquiries into a Fundamental Rights application yesterday, stating that the courts do not have the technical competence to go into the issues raised in the case. This decision was made in a case filed against the Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation. The BBC Sinhala service reported that the Chief Justice further went on to state that the lawyers should not file cases relating to all problems within Sri Lanka.

The lawyers, he stated, should advise the clients to negotiate these problems with the relevant government institutions and to come to settlements instead of bringing these cases to court. He reiterated that the courts do not have the competence to deal with many technical issues that arise in these cases.

This decision by the Supreme Court to discontinue a hearing of a Fundamental Rights application purely on the basis of absence of technical competence is the first occasion on which the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka has made such a decision. The constitution requires that once a Fundamental Rights application is filed, the courts should examine the merits and, if there is a case to be dealt with, the court should issue notice to respondents and fix it for hearing. After the lawyers file all the papers and make their submissions at this final stage, the court is expected to make a determination on the issue. This is the first occasion on which the court has refused to follow the constitutional provisions on the basis that the court has no technical competence to go into the issue.

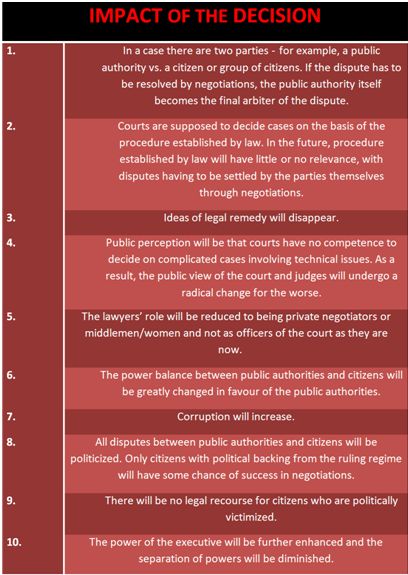

This decision by the Chief Justice will seriously undermine the position of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court judges are expected to have the competence to adjudicate on all matters that are placed before them on the basis of the law in Sri Lanka. The Chief Justice is reported to have said that the lawyers should take up these cases with the relevant public institutions and negotiate and settle these matters.

Distinction between litigation and negotiations

The litigation process begins with a party that is of the view that his/her rights have been violated by a government authority and that s/he should have recourse to the law in finding redress for the violation. Referring such a matter back to the negotiation table takes the whole issue outside court. The jurisdiction of the court is sought by the litigant on the basis that s/he has certain entitlements by way of the law. He comes to court on the basis that the court will ensure that his entitlements would be respected by the public authority. He refers the matter to a decision by the court and not to a decision by the public authority, that, in the first instance, has violated his/her rights.

By depriving litigants who contest the matter before the courts, the rights of the litigants are being violated in a serious manner. Once the court decides that it will not go into this matter and will not allow the normal legal process to take place, a citizen is placed outside the due process of law.

The result is that the litigant is left to the good will of the public institution and, if the public institution is not willing to correct the wrong that it has done, the matter ends there. This will provide enormous power to the public authorities to violate the rights of citizens as these authorities will know that the courts will not entertain applications relating to violations by them, on the basis that the courts lack competence of deal with these matters. The likelihood of the authorities more blatantly violating the rights of the citizens is a possible consequence of this decision by the Supreme Court.

Undermining the role of lawyers

The lawyers’ role is to advise the clients who seek their professional services on the law relating to the issues raised by the clients and, when the clients request that they wish to take the matters to court, to assist them in that process. The lawyers’ role is seriously undermined if lawyers are expected to tell the clients not to seek their remedies in the courts but to engage in private negotiations with the public authorities instead. A lawyer is not a mere middleman.

The lawyer’s role is determined in terms of the legal process and in terms of the redress that is made available by law to the persons who feel that their rights have been violated or that their entitlements have not been respected. The relationship between the lawyer and his/her client is based on the understanding of the grievances of the clients. If the grievance of the client is based on his understanding of the law, the lawyer’s duty is to advise him on the availability or non availability of a legal redress before a court of law. If, on a proper understanding on the law, the client wishes to proceed to court, the lawyer is under obligation to assist him/her. The lawyer’s role is not to advise their clients to give up their legal entitlements. If the lawyer’s role is reduced to the position of having to advise clients to give up their legal entitlements and to encourage the clients to enter into a private negotiation process with the authorities, that is a fundamental metamorphosis of the role of the lawyer. This way the lawyer becomes a middleman to go in between public authorities and his/her clients. The public authorities may well tell the lawyer that s/he has no business to come before them.

The problem of competence on technical matters

On many matters that come before a court of law, whether it is on issues of fundamental rights or issues relating to civil litigation or criminal litigation, there are many matters on which the courts may not have the full knowledge of all the issues that may be raised. The law in all countries has found the solution to this problem. The solution lies by way of expert opinions that may be placed before the courts. The courts could request expert advice to be placed before them by way of evidence and then the court would make their decisions on the basis of the expert opinions placed before them. While the courts may not have technical knowledge about a particular subject, they are expected to have the intellectual capacity and the knowledge of the law and therefore to be able to decide on the expert evidence that is placed before them.

If Chief Justice Mohan Peiris’ position is that the courts cannot have the intellectual capacity and the adequate knowledge of law to deal with the expert opinions placed before them on technical matters, then the issue is not about the absence of knowledge on technical matters but absence of competence on matters that the courts cannot claim absence of competence on. The courts are not entitled to claim absence of competence of the intellectual capacity to deal with the evidence before them or claim that they do not have the adequate legal knowledge to deal with the issues raised by experts on the issues placed before them.

Abdication of the function of the judiciary

If the courts decide that they lack technical competence and that therefore they will not entertain the applications made by citizens seeking legal redress on their grievances, that is a clear abdication by the courts of the functions they are supposed to perform.

When judges are appointed to the Supreme Court, the assumption is that they do have adequate legal grounding and adequate intellectual capacity to deal with all evidence placed before them, including the evidence placed before them by experts. Courts have the right to ask the necessary questions when such evidence on technical matters is given, and to obtain the necessary explanations so that they will be able to adjudicate on those matters. Besides seeking the advice of experts, the courts are also entitled to request from the lawyers who appear before them to place before courts the necessary explanations relating to the issues that the courts are dealing with. The lawyers are by their very profession obliged to provide guidance to courts on the relevant issues that arise in court.

A question that needs to be dealt with by the Bar Association of Sri Lanka

The issue of the Chief Justice declaring that lawyers should go to public authorities rather than coming to court is a matter that the Bar Association should seriously take up with the Supreme Court. By placing their position on the basis of law, the Bar Association should clarify the legal position on this matter. Whatever decision that the Supreme Court takes must be based on the law. If the court makes decisions that are not based on the law, then the courts themselves would be violating the rule of law. The Bar Association needs to take this up as this is a matter that affects the procedure established by the law as well as their own professional standing before the courts and before their clients. In doing so, the Bar Association should take into consideration the questions of corruption that may enhanced by this decision to refer cases back to public authorities for them to be the final arbiters of cases.

When cases are field, a public authority can be one of the parties. The citizen is the other party. Between these two parties there is a contest. What the decision of the Chief Justice means is that one of the parties is given the power to be the final arbiter on this issue.

The Bar Association needs to clarify the legal situation on the technical competence of courts. There is enough practical knowledgefrom the world over on how the courts have dealt with the issue of technical incompetence on some particular subjects. This matter should be brought to the Supreme Court and the matter should be clarified in this way.

In fact, the Bar Association is entitled to take this matter not only for negotiation with the Supreme Court but also by way of litigation in the courts themselves. As this is a matter of enormous legal importance relating to the procedure established by law, the Bar Association need to settle the matter finally and, if necessary, by litigation.

As Sri Lanka is a party to the Optional Protocol of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, there is also the space for the litigant in this case as well as the Bar Association to take up this matter with the United Nations Human Rights Committee.

– A Statement from the Asian Human Rights Commission