President Gotabaya Rajapaksa is filling government with ex-top brass in the name of ‘professionalizing’ island-nation’s politics.

Even at the height of the Sri Lankan state’s armed conflict with the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a civil war that saw brazen insurgent attacks on the capital and government installations, the island-nation’s democracy was never seriously at a risk. Now in peacetime, democracy is under unprecedented assault by the ruling Rajapaksa clan.

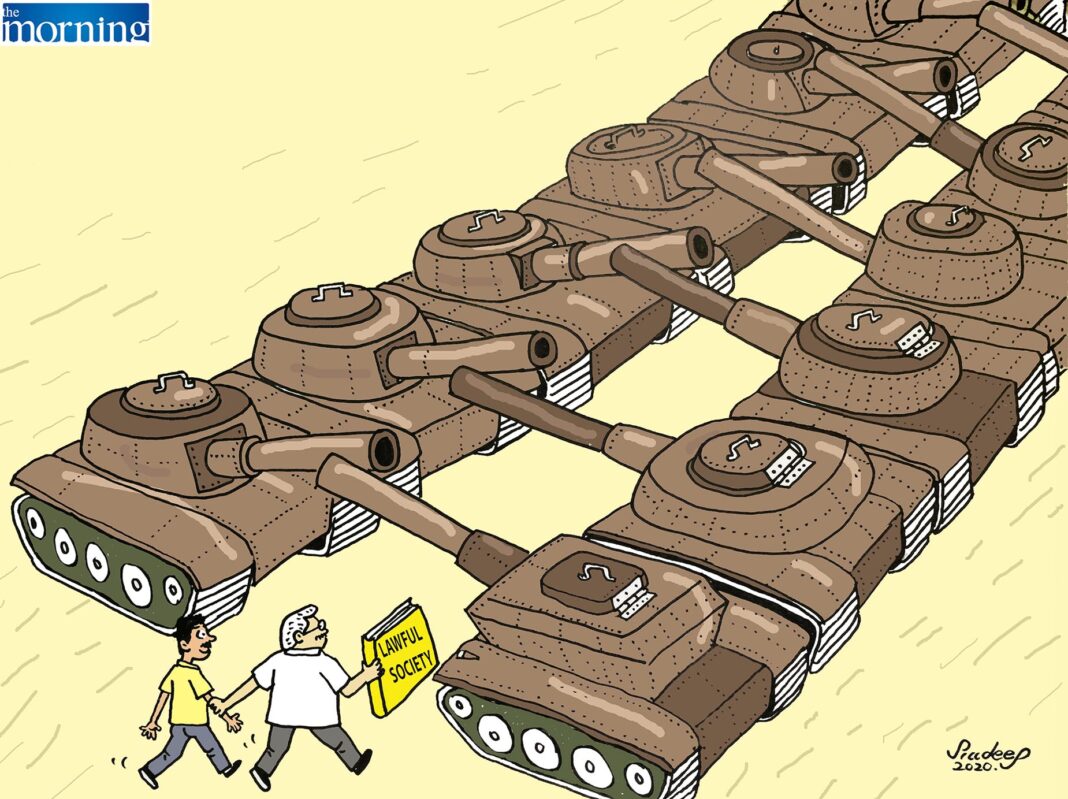

As President Gotabaya Rajapaksa increasingly fills state institutions with ex-military colleagues and loyalists, Sri Lanka’s democratic foundations are slowly but surely being militarized. Observers feel it is only a matter of time before the defense establishment will march on to taking up elected state positions, too.

Gotabaya, who served as defense secretary under his brother Mahinda Rajapaksa’s hardline regime and oversaw the LTTE’s brutal defeat, is now making transformative changes to Sri Lanka’s politics that if unchecked will shift the nation from electoral democracy to a hybrid military-civilian regime, similar to the one seen in Pakistan.

When Gotabaya overwhelmingly won the presidential election in 2019, observers feared that the rise of Sinhala Buddhist nationalist forces would come at the expense of Sri Lanka’s ethnic and religious minorities. What they didn’t realize at the time was that Sinhala nationalism would provide cover and pave the way for the militarization of the state.

This became more evident soon after the Rajapaksa clan’s Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) party won a landslide victory at the August 2020 general elections. Gotabaya immediately moved to establish an executive presidency, as allowed under the 20th constitutional amendment, a provision civil society and other groups previously tried in vain to abolish.

He now has near-absolute power in his hands, power he is leveraging to place loyal soldiers in top administrative positions including as the heads of state institutions and departments.

This is hardly surprising considering Gotabaya’s election campaign was primarily focused on bringing “strongman” rule to Sri Lanka, both to rid the country of the political indecisiveness and fragmentation seen under the previous coalition government between 2015-19.

As one SLPP member put it, “the political and constitutional crisis that gripped Sri Lanka in 2018 made people realize that the panacea for Sri Lanka’s various problems was a strongman rule and the need to professionalize politics.” These two elements have formed the basis of Gotabaya’s political rhetoric and promise to transform Sri Lanka into a “disciplined society.”

While the military is not yet directly involved in politics, there is no gainsaying that the Sri Lankan defense establishment is increasingly expanding its direct control of various civil institutions, including most significantly the police.

Chamal Rajapaksa, Gotabaya and Mahinda’s brother and current minister of defense, has already put the Sri Lankan police’s media division under his Defense Ministry. The so-called “tri-forces” of Sri Lanka will now have a common media unit and police briefings will be given by defense personnel, blurring the line between law enforcement and national defense.

In another unprecedented move, Gotabaya has appointed a serving military officer, Brigadier Suresh Sallay, as head of the feared State Intelligence Service (SIS). The spy agency was previously a part of the police department; Sallay was the former head of military intelligence.

These steps are in line with what many in the SLPP call the necessary “unification of command and control” to better combat the supposed many security threats the island is facing.

The defense establishment will thus now play a direct role in managing strictly civil and political matters, including future political agitations, protests and other forms of political activism by Sri Lanka’s liberal or leftist Sinhalese groups.

Those include the Janeth Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), which has a history of armed insurrections, but also the activist National Movement for Social Justice and various Tamil and Muslim groups agitating for political and social rights.

Jayadeva Uyangoda, a veteran academic involved in Sri Lanka’s past constitutional reform processes, thinks that “Sri Lanka’s defense establishment is emerging as the most powerful political actor” in the country. He believes on current trend lines the military will play a key future role in shaping and determining Sri Lanka’s foreign and domestic policies.

The presence of dozens of ex-military men in government is strikingly similar to the way the Pakistan military has established its commanding presence in many important ministries and departments, turning the democratically elected government of former cricket star Imran Khan into a hybrid martial law regime.

While Sri Lanka has a much stronger democratic tradition than coup-prone Pakistan, to date there has been no political or popular reaction to the ongoing and overt militarization of Sri Lanka’s democratic politics.

There are two fundamental reasons for this: Firstly, militarization has been effectively presented as the “professionalization” of politics, Rajapaksa rhetoric that has been normalized through state media and official propaganda.

Secondly, militarization is seen as acceptable to many because the Sri Lankan military is almost exclusively Sinhalese, the island nation’s majority ethnic group.

Thus many Sri Lankans – not least the Sinhala Buddhist nationalists who form the core of the SLPP’s vote bank – view the presence of “disciplined” Sinhalese in state departments and ministries as desirable, including as a hedge against a possible, though highly unlikely, future Tamil takeover of government.

For Gotabaya, creeping militarization serves his strongman ambitions while consolidating his control through known loyalists and order-takers. By appointing people who were either his military colleagues or who served under his command, he is assuring loyalty up and down the government’s ranks.

Resistance to rising militarization could yet emerge, though. A recent report by the International Truth and Justice Project noted that at least “Fourteen military and police officials now holding crucial official roles served under Gotabaya Rajapaksa during the civil war while he was the powerful and much-feared secretary of defense.”

Indeed, his ex-top brass inner circle consists of those who may eventually have to answer in court allegations of civil war-era abuses, the same report says. But with Gotabaya in power and former top soldiers steadily taking control of the government, the prospects for backward-looking justice are as slim as the survival of democracy under Rajapaksa rule.

January 21, 2021

AsiaTimes